Interview by Camryn Claude

Originally from Yugoslavia, printmaker Tanja Softić has called many locales home, so it’s no wonder her artist practice interrogates the ways we think about the ever-changing nature of place. She asks viewers to examine ideas of home and displacement, memory and history, leading to new insights about the world we think we know. In her landscapes, invasiveness manifests as collaged elements appearing where we least expect them. It was pleasure to learn about her theory and practice in our interview, conducted via email. Our team also had the privilege of visiting Softić’s home to view her artwork and studio spaces, and found Softić gracious and humble, despite her impressive accomplishments. Words cannot express the awe I felt when viewing her pieces with my own eyes. Their success does not rely on scale, but it is a singular pleasure to feel small while standing before them. I couldn’t be more thrilled to share her works with our readers, stunning even within the bounds of a screen that cannot hope to contain them.

—Camryn Claude, Associate Art Editor

Your work is driven by an exploration of migration and memory, and the relationships we develop with the land. Can you tell our readers about how your experience as a Bosnian American—someone of multiple homelands—informs these thematic threads?

Ah, homeland. The country I was born in (Yugoslavia) does not exist anymore. My native language—which I still refer to as Serbo-Croatian—is now called Serbian, or Croatian, or Bosnian, or Montenegrin, depending on where you are in the region and who you’re asking. I have transitioned through three citizenships and one period of being a stateless person. In both my new and old worlds, the wildly outdated notions of national identity and belonging continue to shape politics and society. My view of the world and my work have been defined by what Edward Said called the contrapuntal reality of an exile. In a way, they function as something opposite to maps: the floating elements come in and out of focus, alternatively anchoring and orbiting others, settling nowhere permanently. I cultivate the space in drawing or print that is polyphonic and at times contradictory: I question the notions of background, foreground, direction, and balance. I am not against harmony, but I want to probe into how we define it.

I note several themes of caution in your work, among them warnings about the perils of nostalgia. Why is nostalgia a dangerous lens through which to view the past? And how does memory play into your work in ways that are helpful rather than harmful to viewers navigating a troubling present and uncertain future?

Nostalgia, one of the principal opiates for the masses, can be defined as yearning for a past that never actually existed. America is remarkably good at cultivating, selling, and even exporting it. Look no further than suburban architecture: with precious few exceptions, housing developments are built like nostalgia theme parks. The cornices and balustrades are made out of Styrofoam and screwed or glued onto the façade. Fake lanterns, fake chimneys. All of these Colonial, Spanish Colonial, Mediterranean “styles” serve no other purpose than aping the past and offering bromides to people unable to reconsider the handed-down aesthetic of fear in a time of great cultural and social change. One of my influences, the late architect Lebbeus Woods, called it an aesthetic of “fixed and frightened forms.” In his visionary drawings and writings (such as his book War and Architecture), he calls for a different way of thinking about reconstruction after wars or disasters: structural repairs to a broken building that call attention to war trauma and enable new ideas about habitation, an architecture that witnesses the processes of destruction and repair. He called them “scab structures”: something opposite of capitalist architectural and urban planning practices that are based on the concealment of trauma and brokenness, something that is more complex, more generative, and more collaborative.

Anyone publicly pointing out the obvious holes in America’s rosy self-image will be considered an America-hater by about half of the population. Any immigrant who tries to inspect the cavities in America’s glittering smile will be considered an unworthy ingrate. In my first year in the United States, I quickly learned that asking about slavery, for example, will empty the room in no time. I am not sure what would be helpful or instructive in this regard in my work, but I hope that the layers of seemingly disparate imagery, the absence of “main protagonists,” the ebb and flow, may suggest the alternate ways of thinking about the pictorial space and concepts of place, belonging, and affinity.

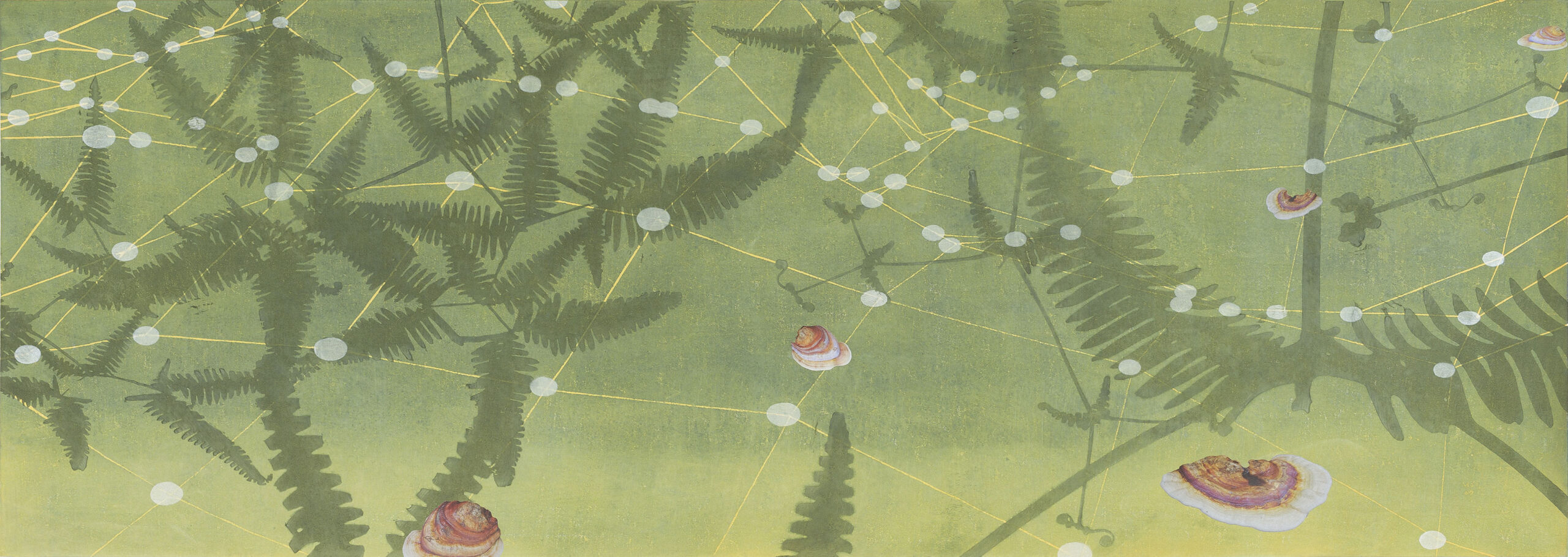

Among other elements of the natural world, invasive mushrooms, which you describe as “unexpected growth in unlikely places,” feature prominently in several of these pieces. Can you speak to the various symbolic roles fungi embody in your work?

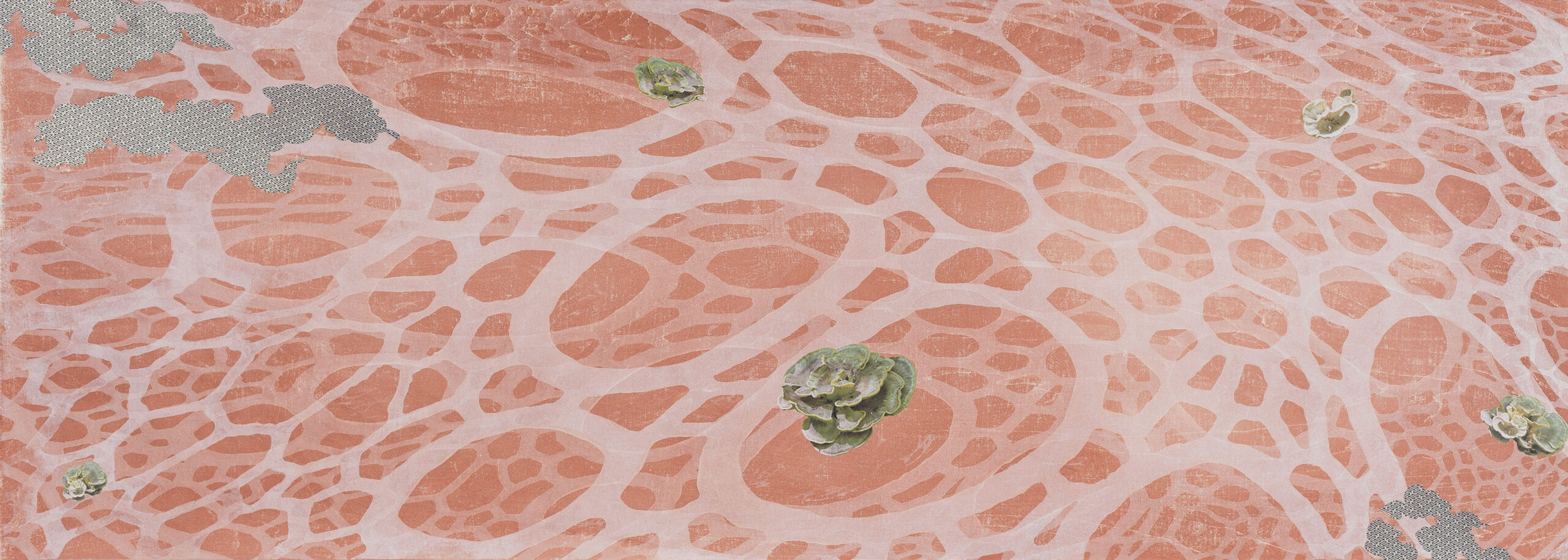

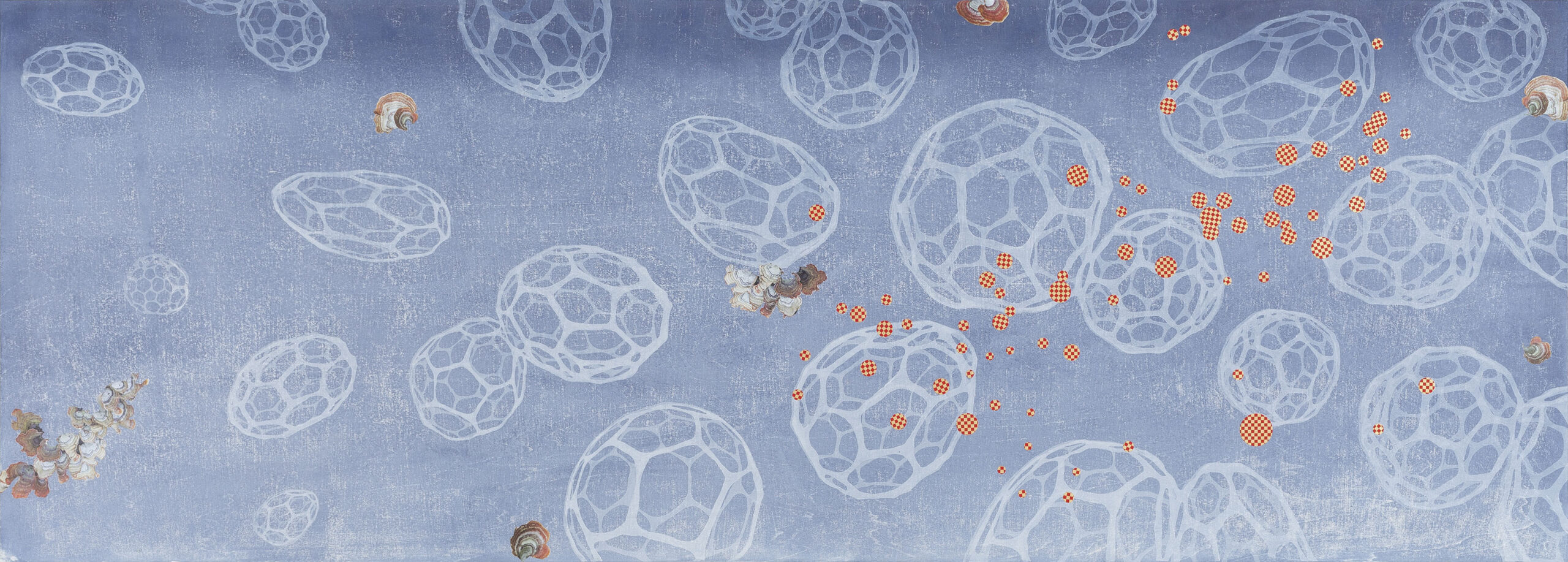

Perhaps because of my history, I am interested in ideas that emerge in the wake of a disaster. What is fertile, what is full of possibility, when we look back at life and culture that has been lost? How can we recognize seeds of renewal in the midst of unfolding disaster? In the last five years or so, I have been working with images of mushrooms and invasive plants, incorporating them into my work as signifiers of the strangeness and interconnectedness of life and unexpected growth in unlikely places, as well as metaphors for displacement, migration, and assimilation. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, raises questions and offers ideas about sustainable life in the precarity of the Anthropocene through many distinct ways of looking at a particular species of mushroom, tricholoma matsutake: its biological symbiotic relationships; its role in processes of reforestation after disasters or logging; its vast underground fungal network; the communities and fringe economies it makes through foraging, trade, and global supply chains. Somewhat analogous to Lebbeus Woods, Tsing offers a vision of a habitable, sustainable communal world where brokenness and degradation are acknowledged, openly mourned, and woven into ever-evolving landscapes. Cultivation of memory without resorting to residual concepts or nostalgia is possible: attention, as Simone Weil has said, is a form of prayer. And it is the beginning of understanding, conversation, and action. I want my work to be informed by attentive, creative openness to a shifting terrain and its surprises—not unlike the kind of awareness one would need to forage for mushrooms, cross the sea to uncertainty in a flimsy boat, or set up home in the ruins after a disaster. I try to listen to the present and envision the possibilities in the future.

Some of the most intriguing—and even playful—tension in these pieces comes from the layering and juxtaposing of objects from the natural world with decidedly human-made objects and architecture. How would you characterize the relationship between these aesthetically opposed items?

The world is an immense thicket of objects, images, and phenomena, and we are tasked with deciphering it. In that process, we seem to keep adding to the thicket. Today’s media- and technology-saturated world is hurling the images at us at an astonishing speed. I have read somewhere that an average person today sees more images in thirty seconds of their waking hours than an average citizen of Florence in the 16th century saw in their lifetime—and that was Florence, at the height of its artistic glory, not some remote village in the mountains. Technology has and continues to change us. The juxtaposition of these forms is sometimes about drawing connections between images that have no obvious semiotic links, and sometimes about contemplation of what remains incomprehensible, just a sheer sense of baffled wonder. I am glad that you find it playful—because playfulness and humor are what we have when we come to the point of incomprehension. But it should not be an escape: play, too, can be a method of discernment. Writers are often told that if there is no surprise for the writer, there will be no surprise for the reader either. That also works for visual art, at least for me. I am satisfied with the piece when it surprises me, when elements of the work somehow escape my intent, pulling me out of certainty, balance, or my sense of competence.

I’m very intrigued by the physicality of your work and the labor involved in your process. You’ve spoken of traveling, hiking, and exploring your world as a means of gathering inspiration and materials. Why is this prep work important and how does it eventually manifest in your techniques and in your use of mixed media once you enter the studio?

I get asked “How long did it take you to do this?” quite often, so I guess that the labor involved in making really registers with people. It is difficult to answer: the elements might have come from a photograph taken years ago, or archival research, or they might have been a part of a project that went nowhere and sat in my flat file forever. There are periods when I really do not have much going on in the studio, yet I am working and thinking creatively without necessarily recognizing it in the moment. It took me a long time to stop judging my work ethic: I still struggle at times to accept and honor my convoluted ways of gathering images and discerning their meaning as something the work really needs. But I do not have a choice, and the internal efficiency judge just has to shut up eventually. Fortunately, printmaking and collage are replete with long, tedious, repetitive tasks that give me a space to think.

As an undergraduate major in painting, I loved the process but never knew when to stop. I feel that a painting, like a poem, is never finished, only abandoned, as they say. It is so immediate, so spontaneous and direct, that I have no structure to contend with. There is nothing spontaneous about making a multicolor etching: you have to think of your image in layers (like the exploded-view appliance drawing in the manuals that show you what part is what). So I get to push against that orderliness—sabotage it, if you will—and that tension does something for my making/thinking process.

There are other tensions that inform the work, too, such as the tension between drawing and photography: I love to explore things that are not supposed to work together, that push against each other’s boundaries, that reveal and recognize each other just by the sheer weirdness of their existence in the same piece. My process is quite planned and deliberate, but if I do not let my intuition get in, the work fails.

Paper is, of course, an essential material for most any printmaker, but it’s so much more than a mere delivery device for printed information in your work. Why is paper so meaningful to you as an artist creating in the digital age?

I start all my printmaking classes by talking about the history and impact of print, and in the course of the talk I ask students if they know who invented paper and when. Very few know anything about the origins of the material that has been a substrate of written records of civilizations. They are surprised to learn that something so universally used—every day, by most everyone on the planet—was not part of the foundations of Western civilization. And that, no, it is not made only from wood (may wood pulp, that industrial-age atrocity, go the way of steam engine technology very soon). While paper has been ceding ground to computer pixels for years, it is still very difficult to imagine the world without it.

I am very invested in both the material properties and the historical and cultural impact of paper, its relationship to plants that gave fiber for its making. I think that this intense love affair started the moment I printed my first etching and saw the lines rise from the fibers like dunes (and then I grabbed the magnifying glass!). Later on, I began using Japanese and Korean papers. I got to travel to Japan and witness and engage in Japanese handmade paper processing, quite different from Western traditional papermaking technology. Asian papers have been traditionally made from so-called virgin (uncut) fibers, such as the inner bark of the mulberry (kozo), while Western papers have been made from the leftovers of the garment industry, such as chopped and processed fibers of cotton and linen. That is why Asian paper, ostensibly so delicate, is used in book conservation or kite- and airplane model-making. The long fibers give it astonishing strength, an armature of sorts (Tyvek is a synthetic riff on Asian paper structure—that’s why you cannot tear that FedEx mailer). My larger works depend on this resilience: if I used Western paper for some of my larger drawings—which go on the wall, off the wall, get rolled up, get unrolled, get stained with water media, get cut and patched—I would end up with a pile of pulp.

Your compositions seem to avoid central focal points and typical aspect ratios, which I find compelling because they are unsettling or challenging to the eye without being unbalanced or displeasing. What informs the decisions you make about dimension and scale, the distribution of objects in space, and the paneled nature of your pieces?

The compositions are unsettled and without the center because they investigate the world without center, without solid ground, without permanence in the lives of an increasing part of humanity. My graphic interventions on top of larger backgrounds are in conversation with that reality. Long horizontal formats, broken into contrasting, dialoging panels, correspond with the speed of the climate change and the speed at which we try—and mostly fail—to process the onslaught of information coming our way. These decisions are certainly informed by the artist book formats I have worked in and observed, multi-channel video installations, and other strategies that disrupt a straightforward narrative. It is built as a result of digging into my own “archives” of photographs of mushrooms, invasive plants, memory “loci” in Sarajevo and elsewhere, illustrations, decorative patterns, diagrams, maps, medical illustrations, microscopic imagery, and more. The resulting compositions investigate our priorities and contemplate new ways of living, valuing, and thinking in this new, rapidly changing world.