Interview by Josh Galarza

I first met printmaker Erin Wohletz when they were kind enough to guest lecture in my intro to printmaking class at the University of Nevada, Reno. Erin had recently graduated with their BFA and was fresh from a residency at the Seacourt Print Workshop in Bangor, Northern Ireland. Their life as a globetrotting artist seemed impossibly glamorous to me, a beginner who had yet to gain darkroom privileges and was still going through his “brayer marks are cool” phase. Over the next few years, our paths crossed several times, most notably one day in the studio when I walked in on Erin making fascinating sculptures with resin and canceled—or retired—copperplates, their surfaces still glinting warmly, faintly inked with imagery from print projects gone by. Canceled plates are typically destroyed so they might never fall into the wrong hands—or, in less melodramatic terms, so they’ll never be printed again. But here Erin was, finding a way to usher their used plates to artistic glory, no longer a tool in the artmaking process but the art itself. It’s this innovation that I remember most when I think of Erin. Their constant experimentation made me want to take more risks myself, an approach that saw me to plenty of heights in my own career as a visual artist. I’m so thrilled to share Erin’s work with you, and hope you’ll find it every bit as engaging, challenging, and memorable as we do here at Blackbird.

—Josh Galarza, Art Editor

You’ve made a name for yourself in the printmaking community for your work in mezzotint, an intaglio process that was common through the eighteenth century. Since then, the process has fallen so far out of fashion that it’s rare to meet a mezzotint artist; in fact, you’re the only one I’ve ever known. Can you tell our readers more about the history of mezzotint, the nature of the notoriously laborious process, and how you came to be a champion of this endangered art form?

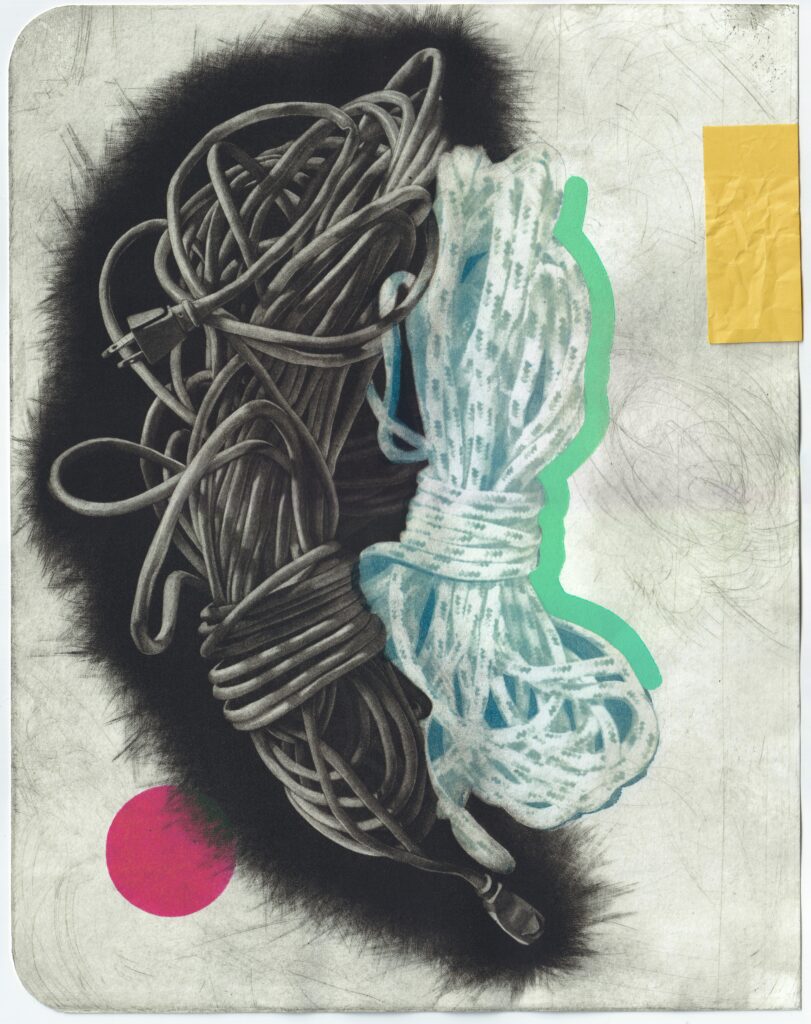

Mezzotint is known for its creation of deep velvety blacks and for its somewhat torturous nature. Mezzotint is a traditional copperplate printmaking method advanced in the eighteenth century that was often used for portraiture. In order to create a mezzotint, the copper plate must first be texturized. A curved blade with hundreds of small teeth is repeatedly rocked back and forth across the surface in thirty-two different directions to form a soft, highly textured surface, like a fine sandpaper in copper. This creates a complex matrix of millions of burrs that create a smooth, even black if printed. This textured surface is then carefully smoothed with a small knife in order to create tonality. The roughest sections hold the most ink, whereas the smoother sections print lighter tones all the way back to white. Additionally, because of the highly delicate nature of the surface, every time a mezzotint plate is run through the press, it is weakened and slowly homogenized and destroyed.

Mezzotint is a medium of violent erasure. Images must be painstakingly scraped from the black void. Being nonbinary and my continued struggle with nonbinary feelings have left me in a space of erasure. My reality is believed to be a fantasy by others, and I have been under constant pressure to repress these feelings and act in a “normal” or “unannoying” way. From a binary matrix (black ink on white paper), mezzotint creates a complex range of tones. The act of creating a mezzotint plate is athletic and aggressive, but the tones created are soft and ephemeral.

Unfortunately, my relationship with mezzotint has become more complicated recently. Due to its highly repetitive nature, the method has injured my elbow over time. It’s now important for me to reduce the time I spend doing it, which is driving me crazy! Even though it’s my favorite drawing material, I have begun looking toward alternate solutions in my prints. Regardless, nothing can beat the quality of print and range of value from mezzotint. It will be my favorite forever!

You describe your works as blueprints about gender nonconformity, which really resonates with my experience of queerness. My years of research in queer theory—to say nothing of my lived experience as a gay man—have left me with the distinct impression that queer identity, particularly nonbinary and trans identity, is predicated on a continual journey toward authenticity. In this model, queer identity is more an ongoing building and renovation project than a fixed state. Can you tell me more about what drives you to document this process as it plays out in your own life?

I agree with you one hundred percent that this journey toward authenticity feels like such a critical aspect of gender nonconformity. The most meaningful aspect of the work is when I can see my experience resonate in the eyes of someone else who has experienced the same things as me. That empathy and understanding is the goal of the work, and that validation is experienced by both me and the viewer. These emotions and feelings may not be understood by the majority, but that doesn’t mean they are fake, imagined, or somehow inauthentic. While I hope the work will one day resonate with people who do not already understand gender nonconformity, I think that’s probably more of a lifelong goal.

For me, nonbinary identity feels extremely natural. I’m grateful that it is becoming more accepted and understood. Still, people who identify with this term are often labeled in the media as silly, frivolous, liars, brainwashed, or desperate for attention. I don’t think anyone who actually knows me would ascribe any of those adjectives to me. It’s frustrating that so many people lack empathy. Even some who consider themselves allies treat nonbinary people as if they’re merely humoring us and our inane ideas. I just want people to consider what it might feel like to be nonbinary, what those experiences might be like. I really just want to bring a bit of empathy and understanding.

While the more accepted narrative of “I always understood since I was a child …” is true for many gender-nonconforming people, it’s not the case for everyone. It wasn’t for me. My self-discovery of queerness has come through a lot of internal struggle and argument. I questioned it on my own, plenty. For me, it’s very important to try to visualize and explain this process and experience.

To that end, your blueprints consist of seemingly disparate objects, images, and textures that you refer to as symbols of queer history. How do you choose your pairings and groupings? Are you driven primarily by compositional balance and harmony? Or are there thematic narrative arcs that lend each piece cohesion?

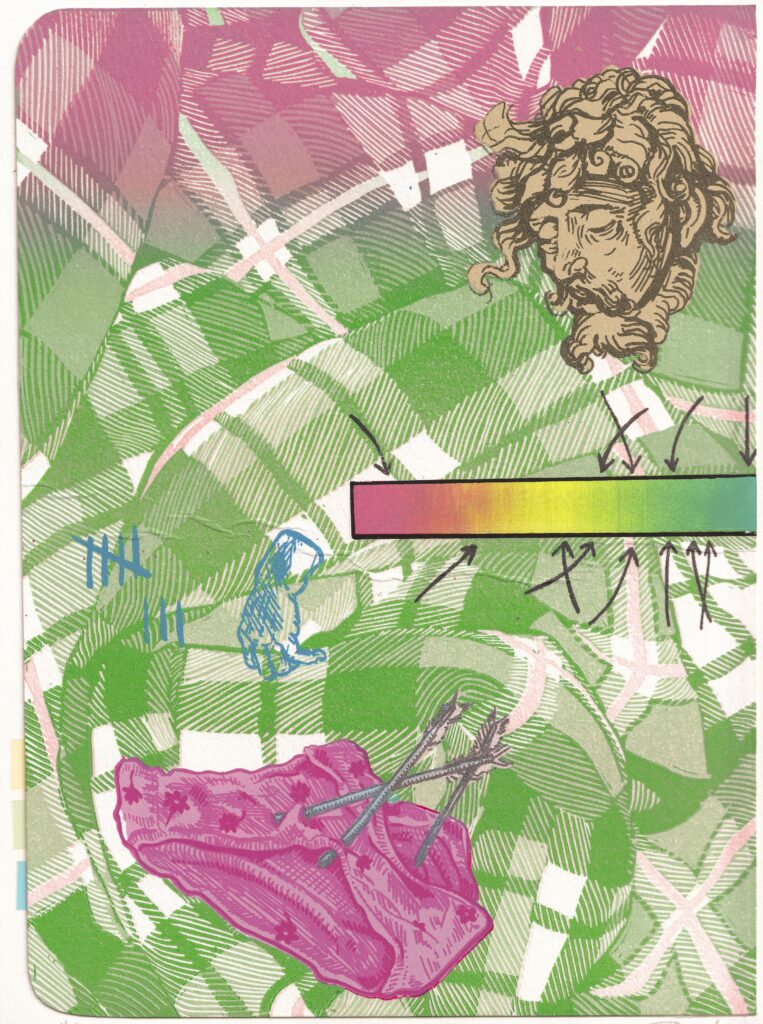

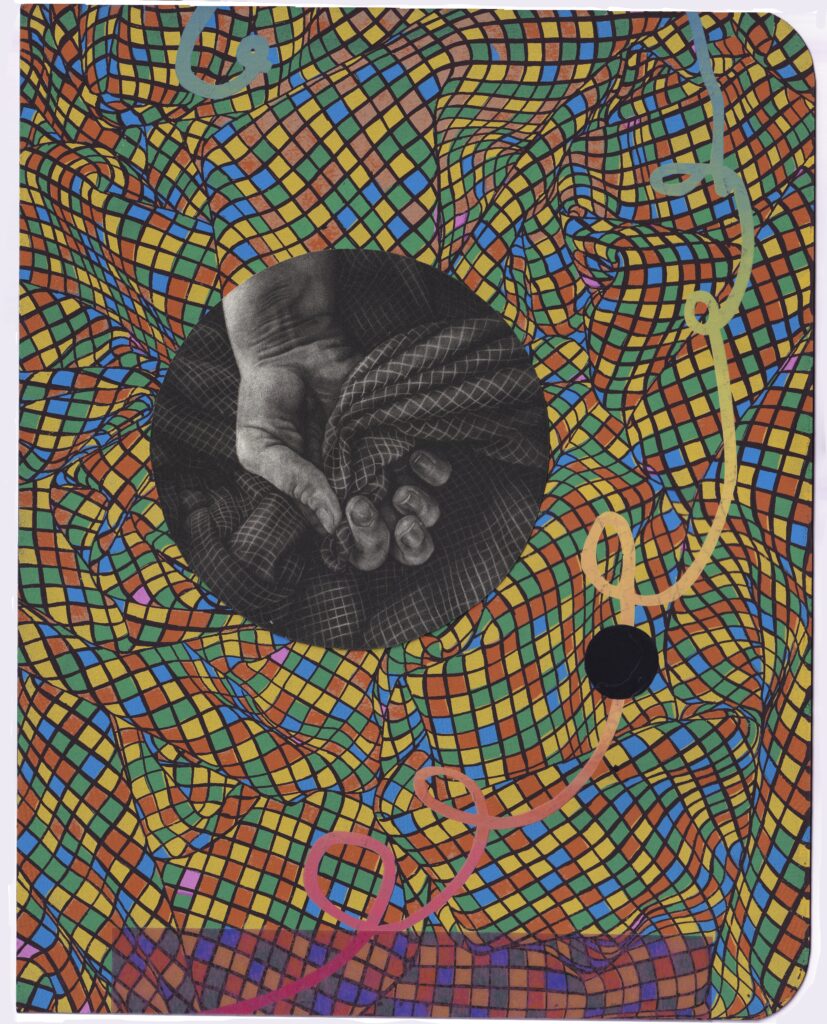

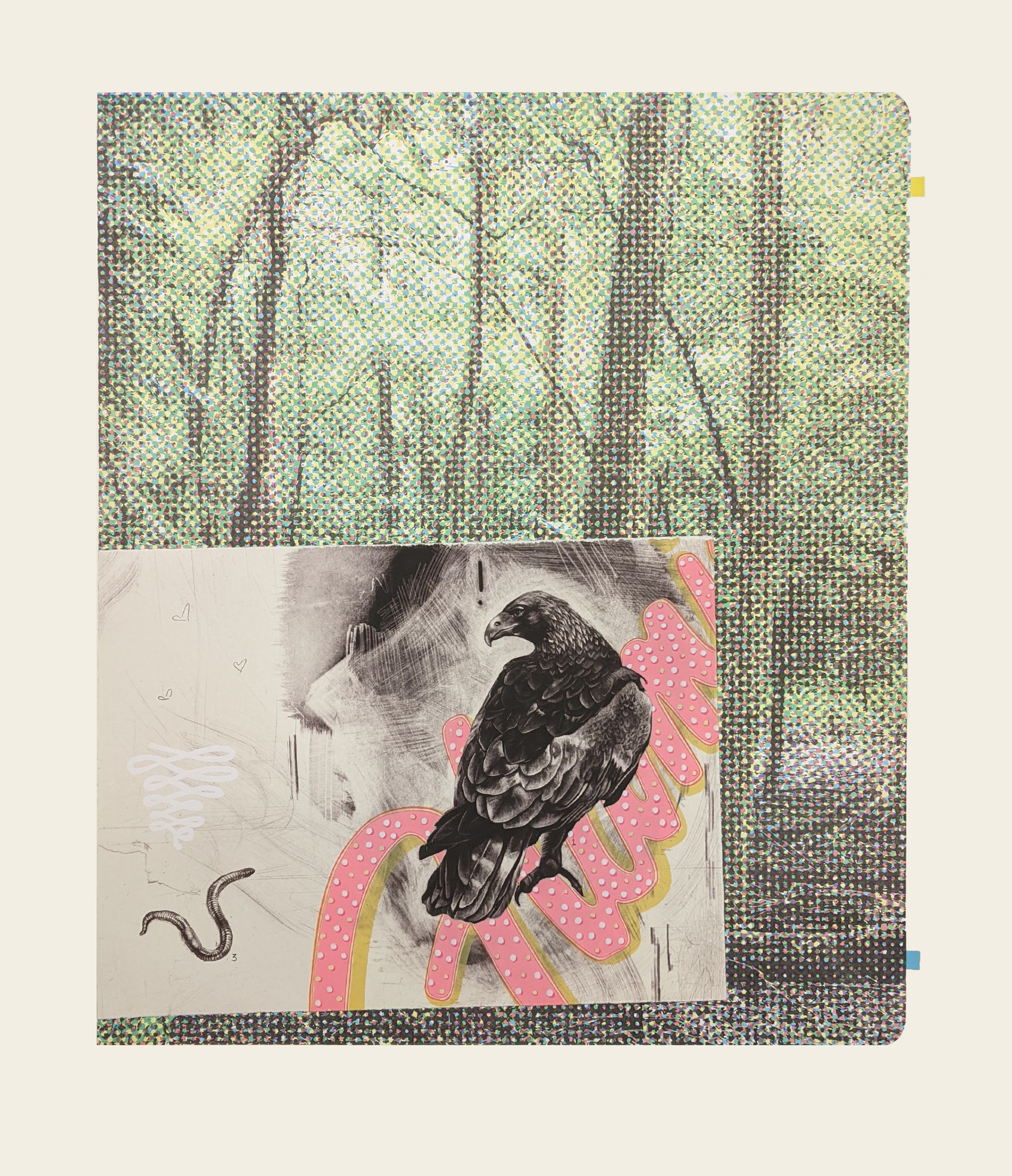

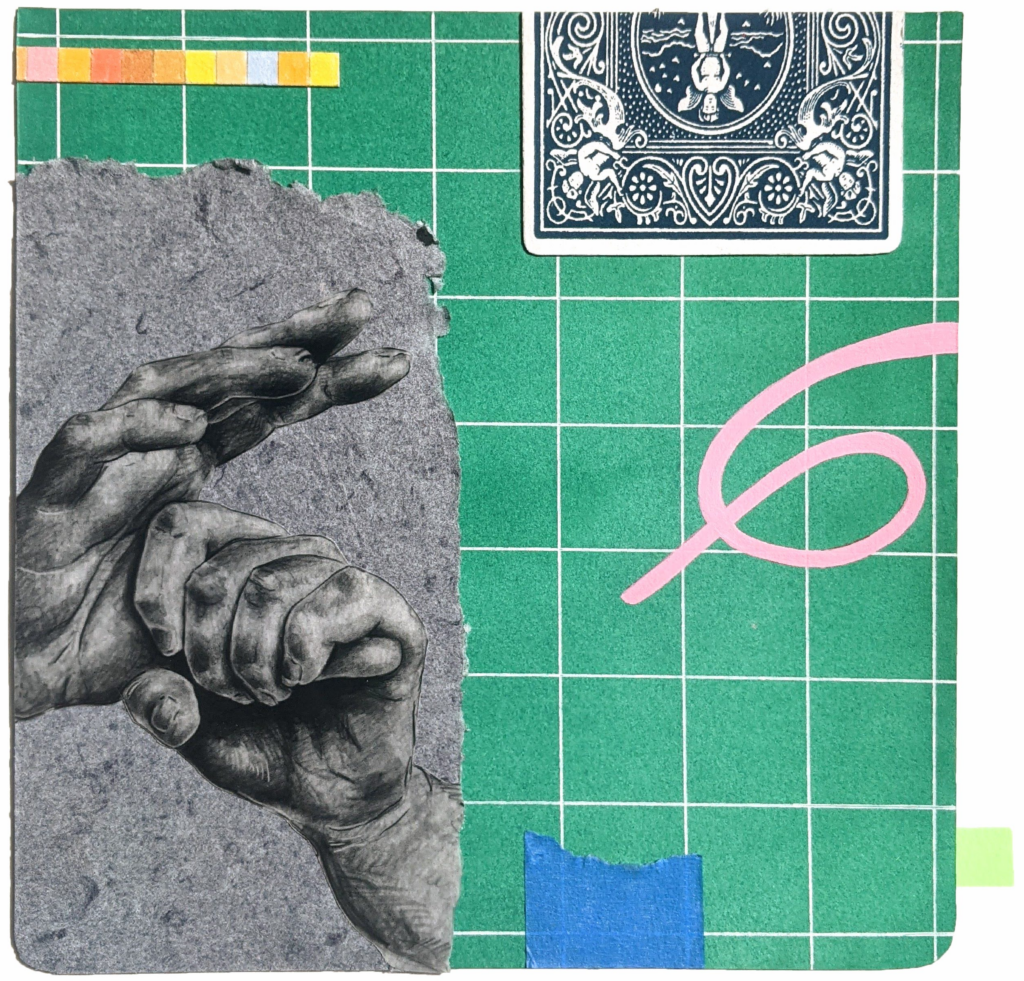

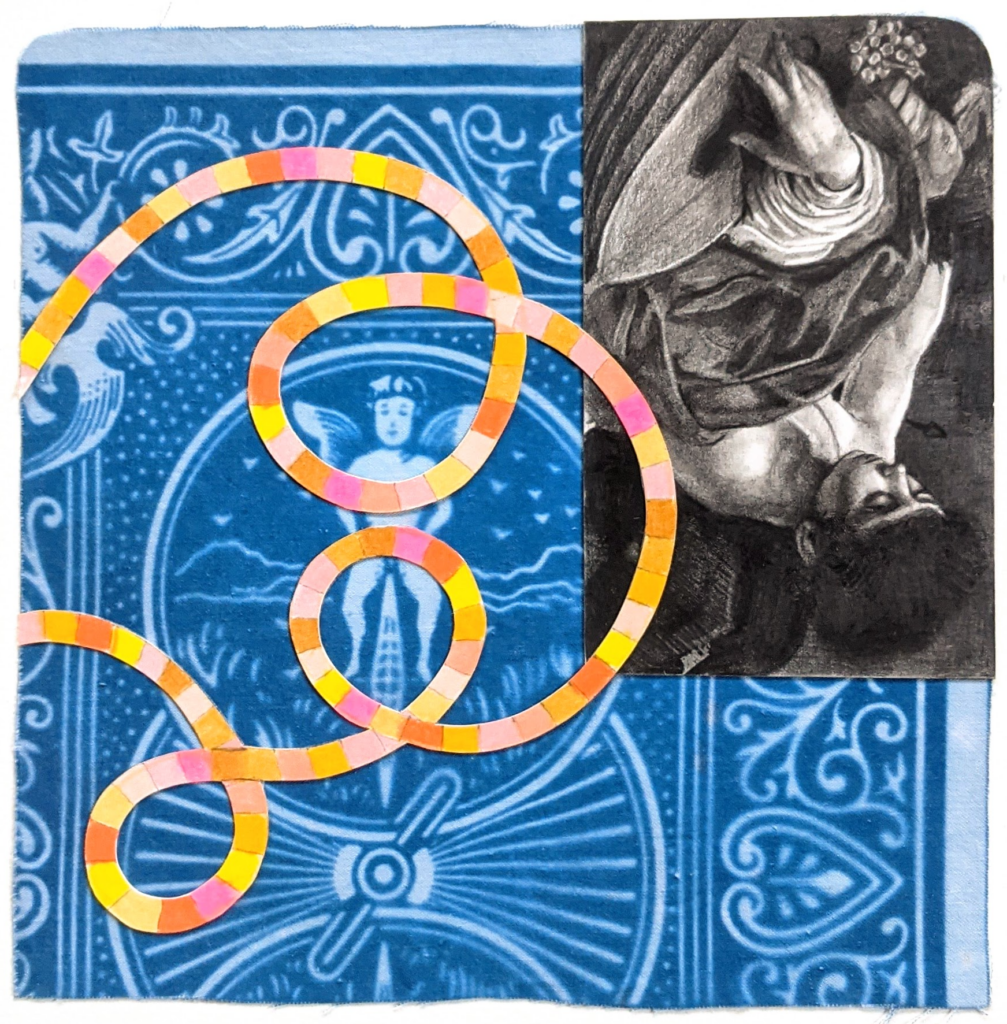

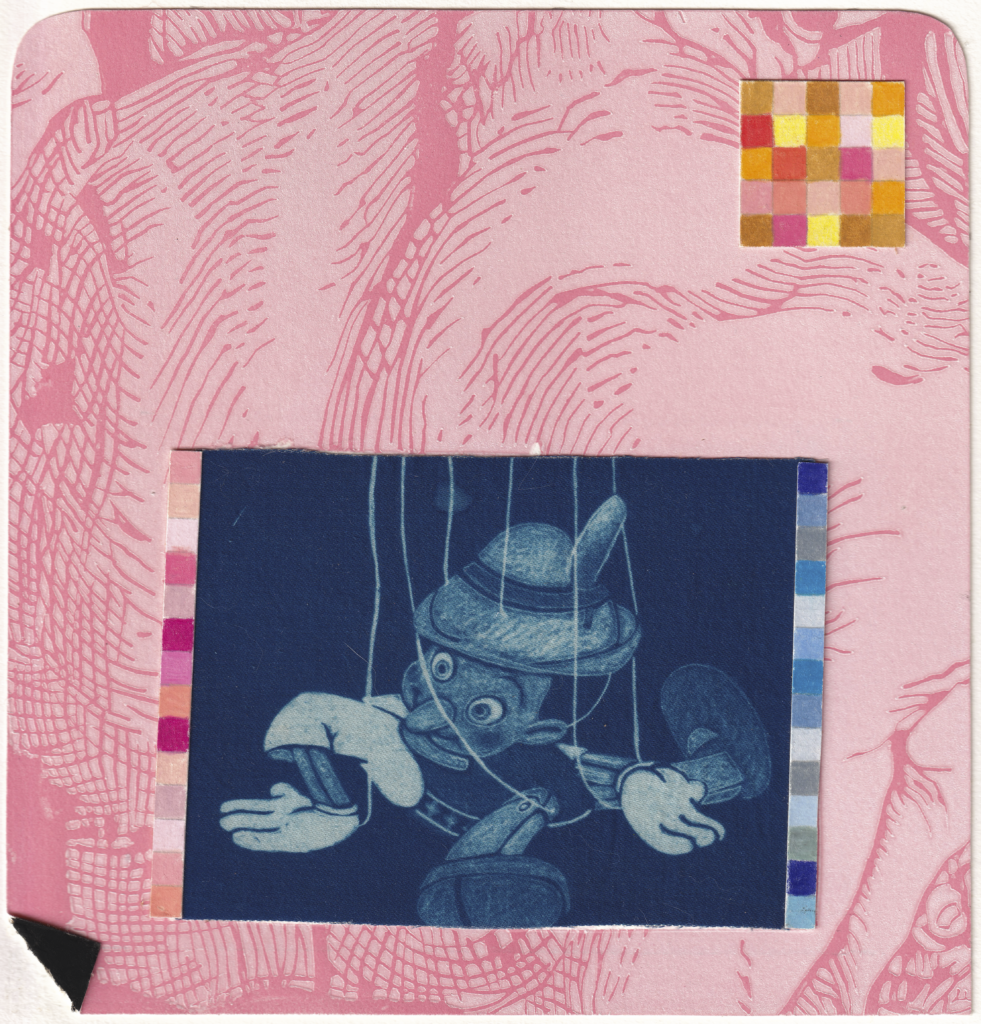

With the compositions and groupings of symbols, there is always a narrative, feeling, or argument in mind. I’ll use my latest solo exhibition, Two Friends, as an example. The idea was that the exhibition as a whole would function as a book whose thesis question was “Am I or am I not a liar?” All of the works were paired into companion pieces, which worked together to approach the central argument. These were not diptychs. These prints had rounded corners on the outer edges and were displayed like an open book spread. Each pair of works functioned as a chapter in the book. The chapters were titled “Risk,” “Bird Art,” “Performance,” “Family,” “Evidence,” and “Shame.” The book ended in an index of hand-written definitions on pages from a yellow legal pad. This list of definitions provided a variety of methods to unlock the reading of each piece.

This meant the work grew from very personal narratives and feelings I wanted to get across to the viewer, supposing the viewer was willing to spend time decoding the work. For the passerby or outsider, the work might have been difficult to decipher. I wanted to speak to concepts that are very difficult to get across with only words, or maybe even things I don’t want to say with words. Inevitably, as an artist, if you make the work you have to talk about it, which has been a challenging aspect of my artist’s practice over the last few years and a major motivator in my recent work.

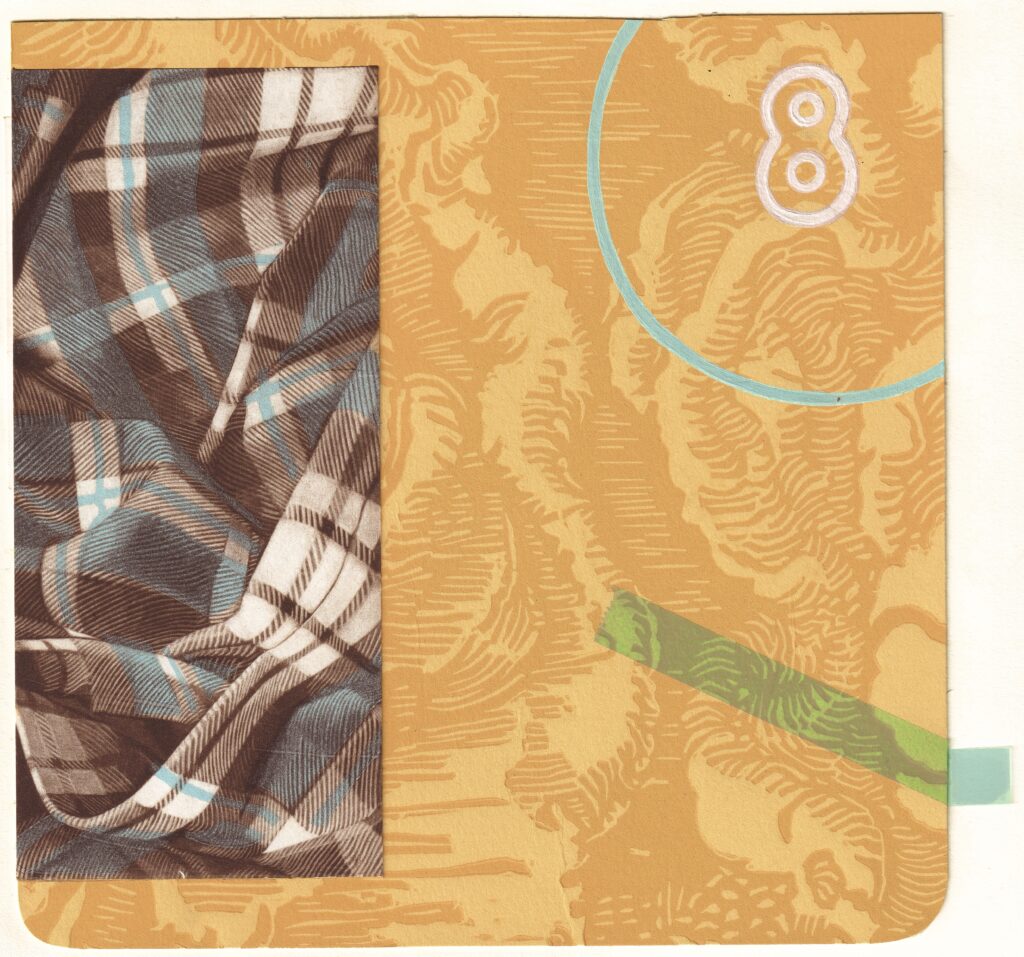

With my most recent series, I am trying to shift the narrative focus away from deeply personal stories and more toward societal narratives. Three major driving forces in the new work are moving from the personal to the societal, striving for truth, and being more direct.

To illustrate how this works, I can point to a new piece, Guts. My works start with the background image, in this case a drawing of pipes from a decommissioned aircraft carrier. Recently, I find myself considering the nature of broken systems and investigating the role of enculturation, politics, and faith as broken systems in America. A broken aircraft carrier pipework felt like the perfect way to visualize that. Then there appears a series of knots, male and female being tied together, a male-to-female pipe converter. Color in my work is often gender-coded: pink as girl on one end, blue as boy on the other, yellow in the middle for nonbinary, and orange and green as being between yellow and blue and pink. In this way the color is like a gender spectrum. So all the symbols, from objects to colors, have specific meanings. It’s not important that a viewer picks up on everything, but I hope they can at least derive a feeling from it. In Guts, I think the feeling is something between worry and anxiety, a gut feeling.

You describe yourself as a “gender archeologist.” Why do you think it’s important for queer artists today to set their sights as readily on the past as on the future? In what ways do you see your contemporary queer work and processes in conversation with those of the past?

Symbolism has always been and continues to be important within the queer community. I am interested in the hidden or secret languages that queer people have been using for hundreds of years to speak to one another, and I think there are many beautiful instances of that in art history. Often double-coded, symbols allow members to communicate to the in-crowd while eluding would-be persecutors. LGBTQ+ persons were consistently using symbology within socially acceptable artworks to talk about their socially unacceptable queerness. Many of these historical queer symbols appear within my work. I seek to recognize and continue this visual queer history.

Something I come to time and time again is the idea of queer evidence. How do you provide evidence or proof of a feeling? How do I provide evidence of queerness? Many LGBTQ+ people will wait until they “have a reason” before coming out. They wait until they are in a relationship, are starting medical transition, or have some other visible proof. I can’t provide evidence of my queerness in that way. I can visualize my emotions for the viewer in the form of a work of art, but that emotion can always be disputed—and probably will be in my lifetime. So I point to evidence of a history of queerness and gender nonconformity existing through time, not only to disprove the idea of queerness as a so-called fad but also to acknowledge and understand queer voices of the past. Feelings of queerness are not new; they have been felt by humans for thousands of years. The language, understanding, and acceptance of them may be growing, but the evidence of these feelings spans through time and through the history of art.

As you mention, symbolism isn’t merely foundational to your work but to queer people as a means of safe communication in unsafe circumstances. Can you tell our readers more about how the language of symbolism has evolved from a means of protection for you—a way to hide the true nature of your queerness, as you’ve described it—into a means of interrogating broken societal systems and diverse infrastructures?

My relationship to hiding! A tough question. I’m a hider by nature. Coming out and revealing myself has been challenging. But I also love challenges, and I love to push myself. I think the long-term arc of my work can be understood as an arc of progressive truth telling. As far back as my BFA or undergraduate thesis, I was thinking about gender in my work. At first, I made work about gender and said it was about death. Really it was about both, but I was unwilling to reveal that aspect of myself to any but a chosen few. The group of people I trusted expanded with each body of work. Now, I’m pretty open with everyone.

It’s tough, especially these days, because nonbinary identity has become this huge political issue. America is so polarized and whipped up that it feels like coming out or speaking about gender is always fraught or risky. Telling people this personal thing can cause them to dismiss me or characterize me as childish and ridiculous, if not flat-out villainous. Opportunities like this to speak about my work to a broader audience always make me extremely nervous (hence the hiding). But I am working on being braver. I do think the message is important. I do think it’s important to speak the truth to the world even if people disagree with you. All I can do is try to be brave, and explain my perspective, and how things feel to me.

I find that sentiment incredibly relatable as there are so many intriguing parallels between attitudes toward genderqueer people today and attitudes toward gay people back when I was coming up. One of my favorite things about my own artist’s practice is exploring how various media can help us in our efforts to be brave and explain our perspectives, particularly when the nature of various materials mirror our thematic content (don’t get me started on the queerness of neons in my work). Can you speak to the various ways you bring mixed media into your prints? It’s rare you use only one printing process, and you often include hand-drawn or otherwise rendered elements.

My artistic practice is based in collage. This has been the case for many years. Even when works are finished as traditional prints, their formative development comes from a construction, deconstruction, and reorganization of symbols across a page. These days I don’t make any single process prints. The compositions reveal themselves throughout the process of creation. I have started printing in a very painterly way. I analyze the piece at each stage and make moves or add symbols as I figure out how to make the piece work. I never have a composition fully figured out before I start working on a piece. Creating is an act of self-discovery, of inquiry. In my mind, I am working through questions and emotions, so it feels natural that the prints should be created in a similar way. One symbol leading to another leading to another. Once I began making prints with many layers, it just made sense that all those layers shouldn’t have to be in a singular medium. Bringing in other media is a great way to keep myself entertained and, in the process, get diverse marks and textures for visual interest.

As an artistic medium, printmaking has wonderful inherent queerness. Prints create variation from the binary, white paper and black ink. The edition is also a representation of sameness and difference. As much as we may try to exert control over an edition, variety inevitably occurs. I reject the idea that prints within an edition should be excluded due to slight discrepancies. This variation is naturally occurring and should be celebrated.

You’re an assistant professor of printmaking at the University of South Dakota, where you share your knowledge and skill with up-and-coming talent. What brought you to academia? Had you always wanted to teach or did the career path take you by surprise? How does teaching affect the evolution of your own artist’s practice?

I really did always want to teach, and I have been teaching printmaking now for three years at the University of South Dakota. We have a historically strong printmaking program, and I feel lucky to have inherited a beautiful and spacious printshop. I love sharing my passions with students who are finding their way in life through art. The feelings I chase in my own work—like when I complete a piece that I actually like and that works, or when I figure out the solution to a difficult problem—I get these same feelings when helping the students figure out a problem, when I watch them fall in love with the process or pull a print that is beautiful and works. I love that part of my job and could do it forever. But, of course, academia has its challenges. I’m sure any professor you know could talk your ear off. Oh, the things I could do with just a little more cold hard cash and an extra couple of hours every day!

My students inspire me all the time. They give me the excitement and the drive I need to keep making art even when teaching and maintaining our printshops takes up basically all of my time. I am constantly working at becoming a better teacher and being better at explaining myself, which does lead to new strategies in the work. In some ways, I am trying to teach the viewer or explain things to the viewer.

Even outside of the classroom, you’ve been heavily involved in your local and even international printmaking communities. You run The Future Is Queer, an online exhibition and index of over one hundred international LGBTQ+ printmakers. Can you tell our readers more about The Future is Queer and what drives you to craft spaces where printmakers, particularly queer ones, can congregate, work, and be celebrated?

Community and the atmosphere in the printshop are what brought me to printmaking. I love creating work with others around. A group of artists striving towards their own goals but working together to learn and to make it all work. The Future is Queer is a passion project that I need to dedicate more time to. The goal is to help queer printmakers meet and learn about one another. I was inspired to create the project when Southern Graphics Council International’s printmaking conference was in my hometown, Las Vegas. There was an LGBTQ+ printmakers’ incubator, where we were encouraged to get to know each other. The event was really eye-opening for me. I discovered just how many queer printmakers were out there and recognized how important meeting these people was to me as a young artist. It was such a simple event, but it meant the world to me. So during the COVID lockdown, I really wanted to create a space for this community to exist online. I would love someday to be able to organize the directory by location as well as name. I also want to create a portion of the website dedicated to LGBTQ+ printmaking art history. There are plans forming for an upcoming in-person exhibition too, so stay tuned.