Profile by Josh Galarza

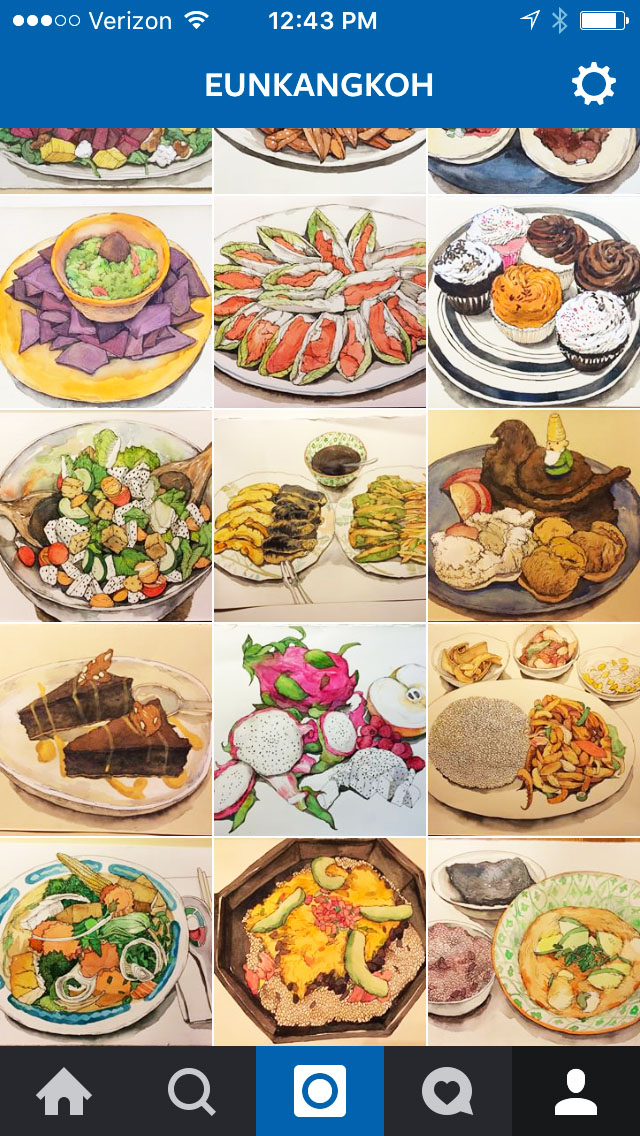

There’s something seemingly run-of-the-mill lurking in printmaker Eunkang Koh’s Instagram page. Were you to hear about her work through the tightly knit printmaking community, you’d expect to find copperplate etchings or linocuts of anthropomorphic animals (or animalistic humans) in her signature, illustrative style. While these do feature prominently, you’ll also find something more at home on the page of an influencer baiting for likes and follows: dozens of images of food. #whatieat. #foodie. #lunchtime. #foodporn. For each of the one hundred days, Koh posted something appetizing and thoughtfully plated, each tableau arranged for a pleasing aesthetic effect, no filter necessary. Indian food, Thai, Korean barbecue. Koh’s food images acted as a travel blog of sorts, each marking another location in the artist and professor’s busy travel schedule. Los Angeles, Brussels, Madrid, Rome.

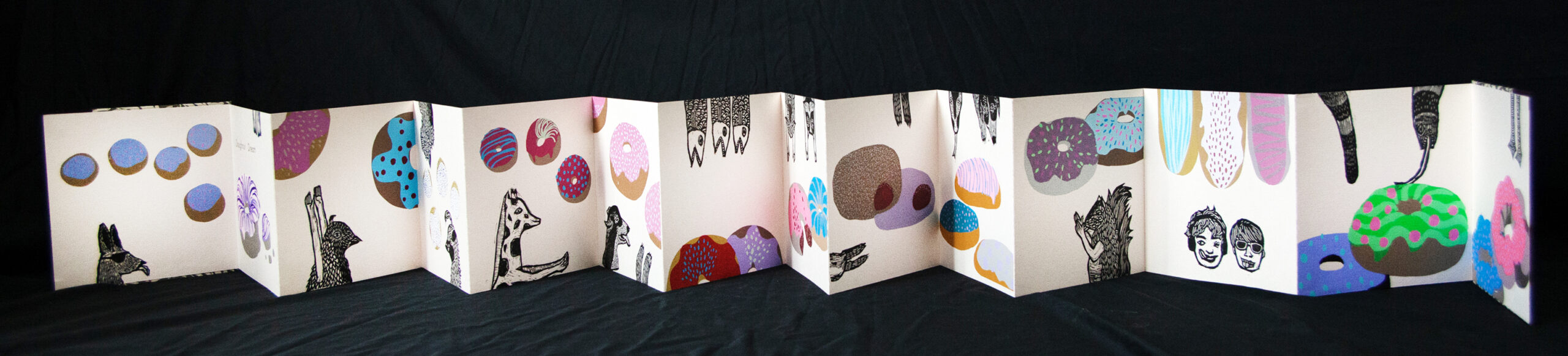

The key difference between Koh and a typical food blogger, however, is that Koh painted her delectable subjects—in watercolor and gouache—with the aim of commenting on how we consume food differently in the Insta-age than we did before a random meal seemed worthy of global broadcast. “I’m trying to explore humanity in a consumerist culture,” Koh says. “We consume food physically, yes, but now we stage the food, arrange it. The food has to be attractive enough. It has to look good enough.” In her What I Eat series, Koh simply took a newly ingrained aspect of Western culture—the idea that some items are more worthy of consumption than others and should therefore be memorialized for all time—and elevated it to an artistic statement. And a gentle critique. More recently, this exploration has evolved into the subject matter of Koh’s latest body of work, Desire, which features plenty of soft-sculpture treats with decidedly erotic undertones.

On the surface, Koh’s dreamy and inviting food paintings seem completely divorced from her often humorous or unsettling printmaking works, which consist mainly of relief and intaglio pieces, but Koh, who teaches printmaking at the University of Nevada, Reno, has been exploring and advancing the same themes in multiple disciplines, including sculpture and book arts, over the course of her twenty-five-year career as an artist. “From the beginning, I was always interested in examining how humans exist and interact in society.” These explorations might focus on how humans treat one another or how we’re fundamentally animalistic. “We often act like animals, and, of course, we are a type of animal.”

A fish who’s gone in for liposuction. An elephant in a three-piece suit. It’s these hybrids that most readily characterize Koh’s work. In representing humans as primal beasts, Koh strives to reveal how we function in various aspects of society and culture (her show titles include The Humanoid in Dystopia, Political Assholes We Wish to Avoid, The Human Shop, and Jungle City). Koh’s recent focus on food, particularly on how desire of any kind overlaps with sexuality, represents a natural progression through one aspect of human behavior. As the digital age of consumerism took hold, Koh’s art followed the trends. “I’m interested in how humans consume, even how we consume other humans. Like with dating now. You can shop for people on your phone. The color of the skin, the career or education—these things are how we’re chosen. The person’s humanity is ignored.”

Koh herself embraces the distillation of humanity in some ways, often reducing her human subjects to the animals she sees when she looks at them. “I was raised with Buddhism, so there were many stories where humans were animals or took on the traits of animals. The animals represented different energies. Because I was raised this way, these aspects of my upbringing are represented in my work.”

In her earliest work, Koh rendered people existing in familiar spaces—on a subway or a busy sidewalk, say—but some of the people would look human and others animal. “People are very political, and sometimes they behave well, other times they don’t. You go into a faculty meeting and people say things—sometimes nice, sometimes not. Is our behavior theater? Or is it real? These places can be a war zone, so I take myself to a more imaginative world. What could my own reality be? You look at the power-hungry misogynist and see a snake or a rat.”

Koh smiles with wicked glee as she talks about the animals she sees around her. Her enthusiasm is infectious, and her perspective is fascinating. It’s hard not to ask what animal she sees when she looks at you (you might find out one day if she cuts a portrait of you from linoleum block, an honor many of Koh’s friends and students have enjoyed over the years). It’s evident that Koh is bolstered by the sense of power that comes from viewing the world through her own secret lens—like when you need to calm your nerves before a speech and imagine the audience in their underwear. When Koh muses on how ridiculous a god might find human behavior, she could actually be describing her own position in relation to the rest of humanity: “If there’s such a thing as a god, it might laugh at us.” If the joke is written by Koh, you can’t help but wish to be in on it.

There’s only one renowned art school featuring a printmaking program in Koh’s native South Korea. “In Korea,” she says, “you get a BFA in art school, then an MA, then a PhD in art, but the only good printmaking program is in Seoul.” If Koh didn’t want to study under the same professor for twelve years, she would have to widen her list of potential schools after completing her BA. “The only option I had was to go abroad. I didn’t want to go to a lesser school. And I didn’t want the same professor for three degrees.”

Koh had studied in the UK for a year as an exchange student, but rather than embrace a familiar location, she set her sights on New York. “In New York, I would get my MA and MFA, which would be like my version of a PhD.” Koh made peace with the trade-off because of the potential benefits of living in the US, particularly the connections and attention she might gain as an artist living in the art capital of America. “I thought I had to go to New York to be an artist.”

But as Koh prepared her applications, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, gripped the world in fear and confusion. “My parents convinced me not to go to New York. My mom was afraid. California was the farthest I could get from New York and still be in America, so I ended up at Cal State, Long Beach.”

Koh credits the decision to attend school in California with completely changing her life’s path. “Had I waited another year, maybe I’d have gone to another country, maybe back to Britain. I could have gone to Australia through a school program.” But Koh had been mentally preparing for America. Attempting to achieve her dreams wasn’t easy. “There were so many restrictions as an international student. I couldn’t get a job or teach. I’d worked since I was eighteen, but I couldn’t do that in America, so I really focused on making art.”

Koh’s time in California was some of the most productive of her career. “If I couldn’t work, I might as well be in the studio. I literally lived in the studio.” When asked what makes a successful artist, Koh unconsciously points to her own behavior. “A successful artist is a working artist. You might be really famous, but what does that mean if you aren’t continuing to make art? Passion. All my friends who work as artists are passionate and make art regardless of money or attention or hardship. An artist makes art.”

It’s that insufferable last hour of a studio class—that time in the class period when students either start packing up early or express their cabin fever by moaning about their aching hands, fried brains, and the utter lack of dissociative substances in their bloodstreams—when Koh opens up about her relationship with alcohol. “I don’t drink much anymore because of my digestive problems, but I always used to say there were only three things I needed in this life: art, friends, and beer.” This sort of casual admission is commonplace in Koh’s printmaking lab. She’s the rare teacher who’ll openly confess to hating grading work. “I give out a lot of A’s. If you’re passionate, if you work hard, you still deserve an A, even if your artistic skills are weak.”

Koh’s irreverence for her own position points to the nature of printmakers as a type. There’s something inherently rebellious about the art of printmaking. Unlike classic disciplines like painting or sculpture, printmaking wasn’t only for those wealthy enough to commission a work. Instead, printmaking developed to quickly disseminate information to the common citizen. The work was not precious. It was meant to be held in one’s hands and shared. So while printmaking eventually rose to the level of fine art—and enjoyed a notable heyday in the age of pop art—it never quite shook its reputation as the messy little brother of the art world (literally messy, since the requisite component to all printmaking is ink, a viscous substance made of oil, pigment, and glue).

Printmaking attracts the misfits—the punks and the queers and the feminists and the counterculture—those whose voices were not historically welcomed in the mainstream. It makes sense, then, that printmaking is characterized by a fundamental sense of community. Wherever minorities meet, they meld. “I loved the community part of it,” Koh says when asked what drew her to printmaking. “Printmakers are community-driven, not so much about pursuing their careers as individual artists. Printmaking is more democratic than other disciplines, about working together.”

Koh’s assertions are further illuminated by how printmakers are employed or how they access the incredibly expensive presses or emulsion exposure equipment needed to print almost anything besides hand-printed relief blocks. There are three main avenues for the printmaker: to teach, accessing equipment on a university campus; to gain employment in a print shop or press, which involves an incredible amount of collaboration to see each internal or commissioned project to completion; or to access a community press, which exist in many larger cities but are all but unheard of in rural areas. (Reno’s community press, Laika Press, founded by Koh’s own former students, only just opened its doors in 2017.)

“I fell into teaching,” Koh admits. Her career as a professor, which she secured after a single teaching job, was merely a way to pay the bills so she could make art. “I figured I’d teach two or three years, and then after my immigration status was worked out, I’d go back to being a full-time artist.” Koh’s attitude quickly changed once she started mentoring college students. “I didn’t like teaching kids or teenagers—and college students can be like children sometimes—but still, I think it’s great to work with my fellow artists. That’s what I call my students, fellow artists. Some of them even become friends and we still hang out.” Koh may no longer be able to tolerate the beer, but two out of three needs met isn’t bad.

One might suspect Koh’s attitude toward teaching is especially relaxed—maybe too much so considering how often she jokes about needing snacks for critique days—but nothing could be further from the truth. “Teaching means so much to me,” she says. “In one way or another, I’ll always be teaching. It’s just a great way to use my knowledge. When I teach, my knowledge comes to life. Does that make sense?”

It does. Teaching keeps Koh sharp and stimulated as an artist.

“Some people are naturally good at teaching, but I don’t consider myself that way. I constantly study and do research to be better. That makes me grow. I’m not just staying in one corner forever, like water that rots.” Koh’s face brightens whenever she speaks in metaphor, a self-effacing expression affected partly, one might guess, because she’s forever unsure if her metaphors are making sense in English. This particular routine might be shaky, but she sticks the landing: “I’m a stream constantly flowing.”

Koh’s mother didn’t know she’d received a C-minus in her undergrad ping-pong class—twice!—until Koh began teaching college herself. Koh’s grin when she speaks of the stain on her permanent record suggests she might get a small thrill out of disappointing her mother. “I had to request my transcripts from Korea. My mom had some questions for me.” Koh’s words might conjure a particular image in the mind of an American: in some dated but perfectly tidy sitting room, the poor, long-suffering Asian “tiger mom” sets her china teacup down and hangs her head in shame at the news that her daughter was anything less than perfect.

It’s moments like these—moments when you feel a pang of guilt over reducing a person to an ethnic cliché—that you become hyper-aware of the fact that Koh lived a whole life across the Pacific before immigrating to the US. This realization begs an obvious question, one you’ll quickly regret asking: in what way does Koh express her heritage in her work?

To the Eurocentric eye, Koh’s work is mysteriously devoid of references to her homeland, but of course such a thought, fleeting as it may be, is embarrassingly ignorant. “I’m from a country that was colonized,” Koh says. “Is my perspective of Korea what I think it is, or did I learn from the Western perspective what my heritage is about?” Such an unsettling concept can be hard to grapple with. What does cultural identity mean to those who grew up drowning in the simulacra produced by a wholly different culture? “That’s a common identity issue any colonized country has to suffer. They have to reinvent themselves. I didn’t want my perspective to be what I was taught to believe, so in my work some of the ideas and philosophy are from my heritage, for sure, since that’s who I am, but not necessarily this idea of Asia-in-quotation-marks, not what the Western world believes Asia to be. Korea is a very contemporary country. It’s not the eighteenth-century cliché many people in Western countries imagine.”

Suddenly, it makes perfect sense that Koh’s animalistic images could reference people existing anywhere in the developed world. Koh’s Korea isn’t all that different from America, Western Europe, or anywhere else possessed of contemporary affluence. “My work is influenced by what I’ve seen. I’ve spent twenty-one years in the US. American culture is part of my culture now. People ask, Why don’t you make art from your culture?” Koh shakes her head in frustration. “This is my culture.”

Shortly after arriving in the US, Koh was driving home to her apartment in Long Beach when she was accosted on the street by a stranger. “He yelled ‘go home!’” she says, clearly amused by the story now. “And I was like, What the hell? I am on my way home.” Koh thought the racist was merely distressed that a woman was out on the street instead of home cooking. “I thought he meant go home to my house. My roommate—who was white—was so furious when I told her what happened.”

Though Koh was in her late twenties, racism was still a relatively new concept to her. She’d grown up as a member of the majority in South Korea, enjoying the opportunity that came with relative ease to the middle class. Koh displays no hesitance or shame—as those who suffer from white guilt might—when she casually cites her Korean privilege, a term that rings somehow off to the American ear. “I’ve had two experiences. I lived as a majority. I was entitled and didn’t know about minorities. When I experienced racism in America, it really hit me. I didn’t know what it meant at first.”

Much of Koh’s education in minority living came through the efforts of one of her dearest friends, a gay man by the name of George. “Back when Netflix was new, you know how you would have a list and they’d send the movies? George would say, You should watch this movie, that movie. I’d put them on my list and forget all about them. Then they’d show up, and I’d be watching all these gay movies like, What’s this? I wasn’t interested in two boys or two girls falling in love.”

There’s no dismissal or disrespect in Koh’s recollections, only the usual surprise and mild disinterest most heterosexuals displayed toward homosexual sex and issues at that time. Even though the movies didn’t initially capture Koh’s attention, she understood what they meant to George—and what they could teach her about herself as a new citizen of America. “I thought, This is how my friend must have felt in mainstream culture. I knew that it must have been hard for him.”

It’s clear that Koh’s attitudes toward opportunity have been strongly influenced by George and the myriad friends of all backgrounds she has collected across the globe. “People complain that a minority individual will get a job [over a cis, straight, white, able-bodied person], but for a minority to grow up and succeed is so much harder. If a minority person can be competitive, they deserve a chance.”

Professorships in printmaking are remarkably—scratch that—abysmally scarce, and though Koh doesn’t state as much, one might guess that she’s experienced her share of detractors, those who’d suggest she landed her position because of the disadvantage boxes she ticks off merely by existing in this place at this moment in history: she’s a woman; she’s an immigrant; she’s of a racial minority group. But Koh is the unique individual for whom advantage and disadvantage collide in incredibly complicated ways. Did she get where she was because of her early privilege in South Korea? Or was it because she was a member of several disadvantaged groups in America and therefore uniquely attractive to liberal arts programs? Koh’s life doesn’t add up into a neat equation: A privileged young woman enjoys a level of education many minorities are barred from. Said woman immigrates to a country where her privilege is stripped away, but she receives a consolation prize: the general attitude that women and minorities are more deserving of opportunity since their struggle is greater than that of white men.

Can one characterize Koh’s life journey as a struggle, though? In what ways does her experience compare to that of a native-born American of color or queer orientation? And is it fair for these questions to eclipse Koh’s hard work and talent, two attributes she demonstrates in spades?

Perhaps Koh’s friends provide the best answer as to why and how she ended up where she is today. “My American friends say I’m a true American. I moved to the US with a dream. I achieved the dream. I embraced the culture to make a new culture within me.”

Koh cites one of her fellow Korean friends when explaining this idea of a “new culture.” “My friend says she’s ‘minimally Korean,’ but I say I’m half Korean. It’s still a big part of me because I spent half my life there. I grew up there. I’m not minimal. I’m at least half.” Such abstract quantifications make Koh laugh. “I became a proud American with a pioneer spirit. I rejected what I was taught to believe and created my own identity. I don’t like being told what to do and who to be.”

If America is the melting pot of the world, there’s no denying that Koh brings more ingredients to the kitchen than most. Minority or not, privilege or none, Koh truly does embody what it means to be a modern American, and not just because her Instagram overflows with pictures of mouthwatering meals. Like any American success story, Koh seems confident and satisfied in having achieved her dream. When asked what animal she sees when she looks in the mirror, Koh lifts a limp wrist to her mouth and mimes licking a paw. “I don’t know if I’m a cat, but I like the idea of being a cat. I’m cute and sassy.” And deceptively powerful. It’s hard to imagine any canary standing a chance against her.