Interview by Josh Galarza

While sitting in the audience of a Nevada Arts Council judging panel way back in 2011, I was so struck by an offhand comment judge Debra Gwartney made about the nature of creative nonfiction that I’ve carried the insight with me to this day. She was evaluating my work—which came to her anonymously, like those of every entrant—and was troubled that each essay in my packet tied up in a neat bow. Sometimes, she said, as essay should “open into complication.” Those were her exact words: open into complication.

A young, budding writer at the time, I couldn’t quite understand what Gwartney was getting at. Shouldn’t my stories tie up neatly? Shouldn’t my insights be clear and resonant? Eventually, like any writer who dedicates himself to creative nonfiction, I came to understand that an essay is an exploration, not an explication, and that writing from life means dedicating oneself to the journey, not the destination.

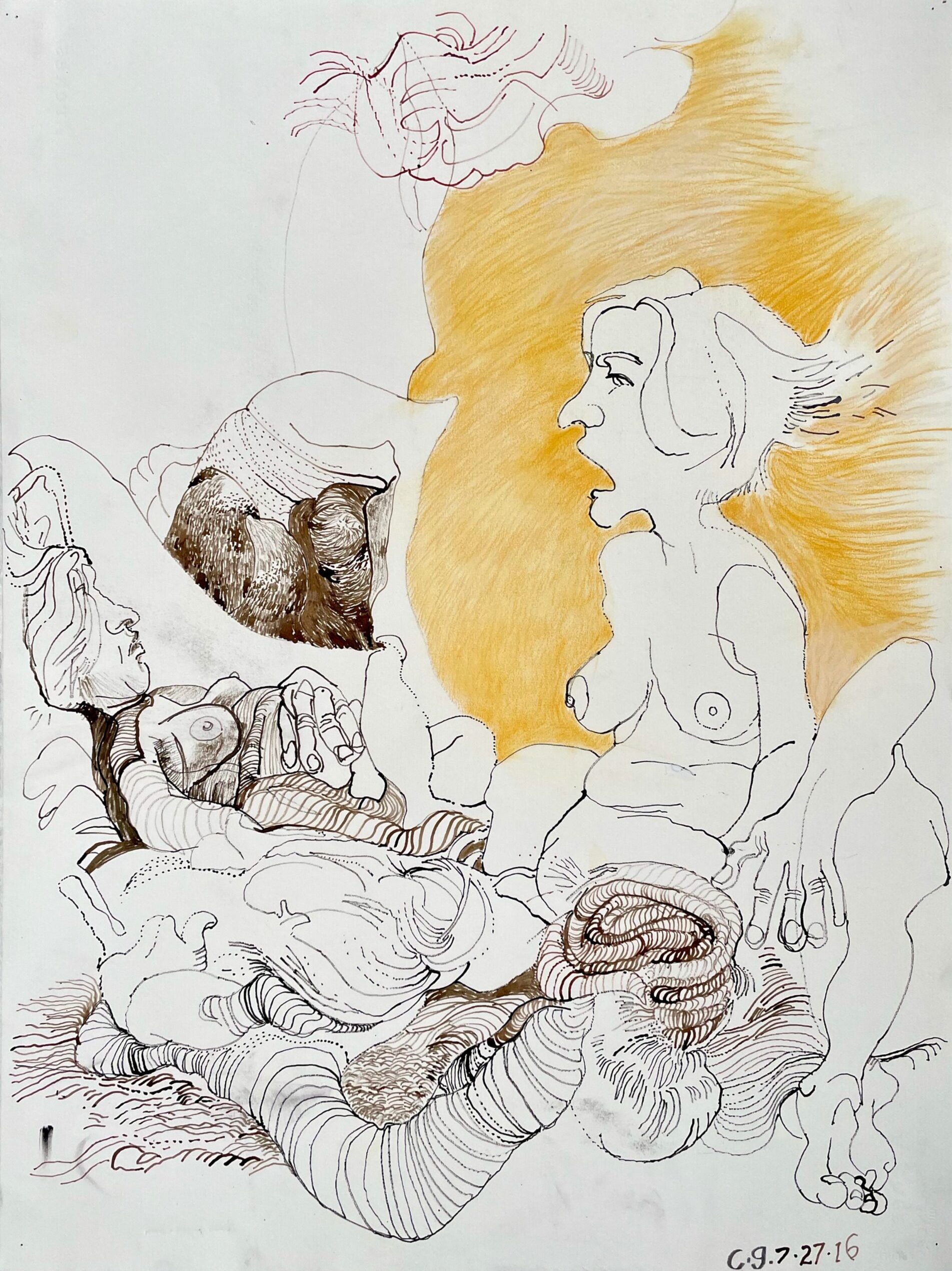

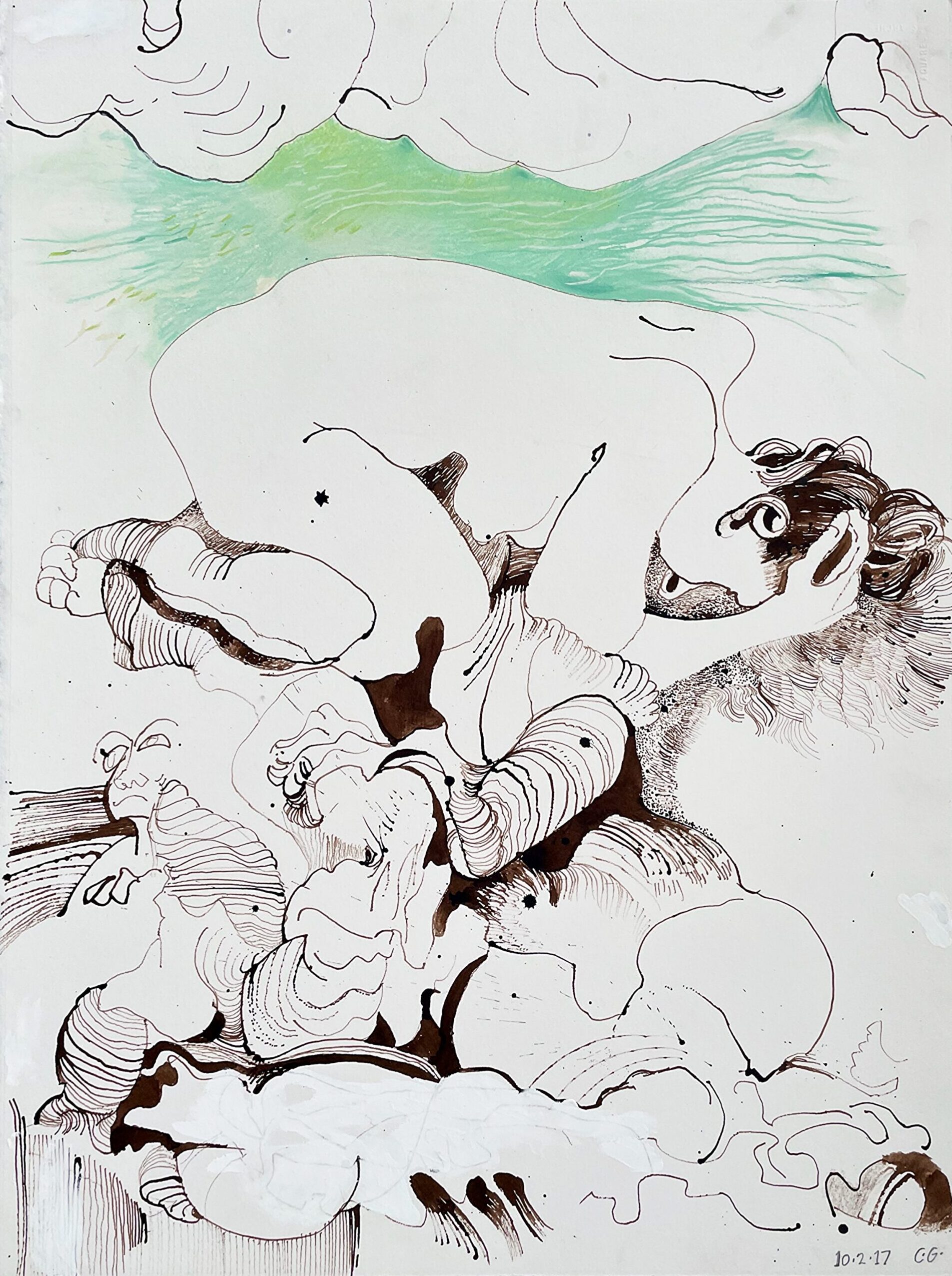

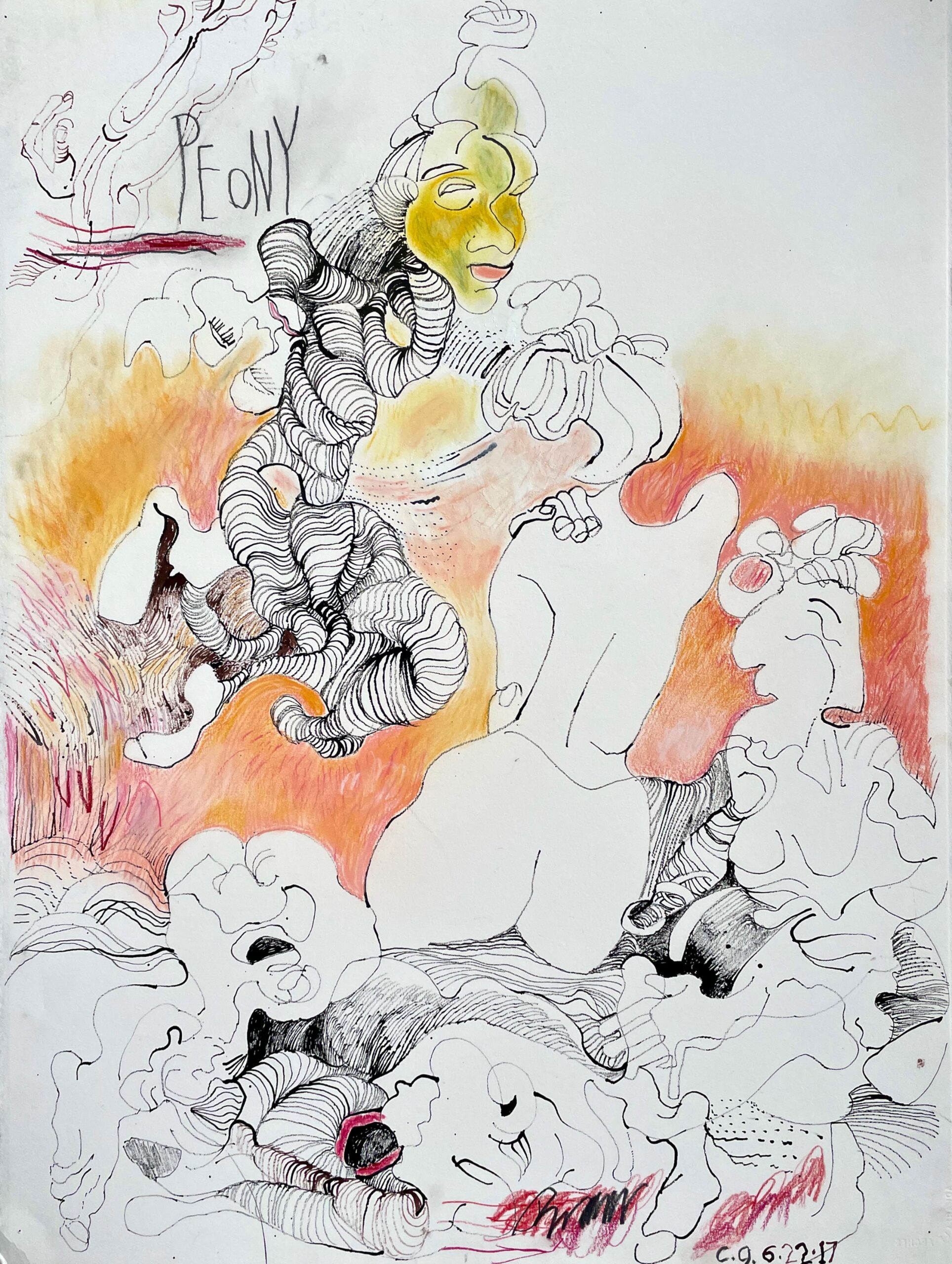

What first drew me to artist Char Gardner’s series of life drawings is their exploratory nature. These are images that open into complication. They turn themselves inside out, twist around, and open up all over again. The subjects seem unwilling to settle into a comfortable composition with a set of identifiable rules or norms within the universe they inhabit. Gardner’s subjects press against compositional space rather than conform to it—a result, I eventually learned, of her process, which saw Gardner following the movement of her models in real time. Each work is an experiment that finds its way spontaneously rather than along any predetermined path toward a clear narrative or thematic insight, and each work, while providing a feast of intrigue for the eyes, leaves the viewer wanting more, not a single neatly tied bow in sight.

—Josh Galarza, Art Editor

The circumstances that led you to create this body of work, Drawing Life, seem like an unexpected gift. Can you tell us how this body of work came to be?

Well, I had not been drawing or painting for a while, though I had never entirely stopped. In 1986, I left my job teaching art to children in grades K-5 to help my husband launch his documentary film production company. Gradually, I took on more responsibility in filmmaking so that by the early 1990s—even though I had gallery representation in Washington, DC—I knew I just had to put art aside for the time being (which turned out to be about twenty years). In 2015, we retired from the film business and moved from Baltimore, Maryland, to Rochester, Vermont—a village in the Green Mountains. Here, I joined a group of other artists who had been meeting weekly for many years. They chipped in to hire a model for life drawing. No instruction, just practice. These are some of the first drawings I made in that group. To me, they represent the beginning of living and working in a new environment with new friends. I used the materials I had been using when I left off years before. Mainly ink.

Though these pieces are crafted with various media, they’re primarily works in ink. Your unique methods of applying and manipulating the ink lend them visual dynamism. Can you tell our readers about the tools and methods you used?

Long ago I taught basketmaking with natural materials at the Smithsonian in DC. One of my favorite materials is the root of spruce trees for the way it bends when first dried and then soaked in water. I began using the roots to make sculpture. About the same time (the early 1990s), I sharpened the roots and used them as drawing tools. I love the way they can carry a lot of ink or a little. The nib can be shaped to produce thick or thin lines. Holding one in my hand made me feel as if the root was sometimes making the drawing on its own. All the drawings here were done with spruce roots. I dug them from the nearby Bingo Brook the day before I attended the first Vermont drawing group.

Much of your work is planted firmly in the abstract. Here, though, viewers will note a tension between the concrete and the intangible, the figurative subjects morphing and melding into abstraction. I’m particularly intrigued by moments of erasure. How did this interplay develop?

I don’t know, Josh. This early Vermont work felt very figurative to me. But one thing you might want to learn is that while working with the model, I never changed to a new sheet of paper when the model changed position. I just kept using what I saw and adding to the same sheet. No one in the drawing group worked like that. At first, I thought of it as being thrifty, since one sheet of Arches Aquarelle paper, 300#, costs around fifteen dollars. But everything I do is so intuitive. That had to be part of my motivation—to not know where I was going or where I would end up. Kind of like writing creative non-fiction (for me, anyway). At some points, I was using white gouache paint to “erase” some lines. I don’t think I did it very often.

Speaking of paper, the printmaker in me—so basically the paper nerd—would love to hear more about the importance of the paper you use as a foundation for your work.

My paper is produced in France by Arches, one of the foremost papermakers in the world. One hundred percent rag. That’s why it’s so expensive. It’s archival as well. I have made paper in a friend’s studio before. On a small scale, anyone can do it—watch YouTube for a glimpse. But for my purposes, I need the skill of the masters. And it really matters to me that I am in love with the surface of the paper I use. It needs to take the ink or paint perfectly or I don’t want to mark on it.

When I first viewed these pieces, I immediately saw a kinship with magazine illustration styles of the 1960s and -70s, both in the line work and the warm color stories. Do any influences stand out to you from this period?

I was eighteen in 1964, so I was visually aware of my surroundings art-wise. Early on I was drawn to the work of Ben Shahn, Bob Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly. Louise Bourgeois was not “re-discovered” until the ’70s, but she is an influence. Georgia O’Keefe, always. I made psychedelic posters in Berkeley in 1965-66.

While these works are products of life-drawing exercises, their titles point toward the experiences of women existing in the female body. Can you speak to the thematic threads that emerged as you crafted these pieces?

Your observation is probably by chance and the result of the different times you have grown up in. As I said, I work intuitively, so what comes out is from my sub-conscious self, and I make no claims except that I think I am honest as I can be, and I’m a sponge soaking up everything, so surely it finds its way onto the page despite everything. Since I am a woman, nearly eighty years old, and I exist in a female body, the titles relate to everything in my spongey old brain.

You’ve said that the intent behind your art is experiential and that you don’t predict the results of any given piece. In a culture that is predominantly market and consumer centered, what is the appeal for you in centering your experience as a maker over the resulting product?

Market-driven, consumer society is the enemy of art. The “Art World” is in ruin. I don’t even want to be shown in a gallery. I’d rather be my own boss. I gave myself a 75th-year retrospective a few years ago in an empty store front in my village. It was very satisfying to pull together work from all those years. Many people came, and I used it as an educational experience, talking about ways of working and common themes over the years. People loved that I spoke in normal language. They felt at ease learning something and not being intimidated to open their mouths. In today’s world, DIY is the way to go!

You’re also an essayist and former documentary filmmaker. As an author and visual artist myself, I’m always curious about how various forms of expression and storytelling intersect for others whose practice can’t be contained in one creative arena. How do you see your work with words and film in conversation with your visual art?

Thinking back, I believe it’s all-of-a-piece, as any artist’s work should be. Look at Phillip Guston—his early work was brilliantly figurative and influenced by the Renaissance. His late work (the best) had a hard time getting shown in the ’70s. But it’s all-of-a-piece because it came out of the same artist. All my favorite artists lived long lives and proved this to be true. Right now, I’m in love with the British painter Rose Wiley, who is ninety-one. She insists that when she was married to the painter Roy Oxlade, and he was painting and she was making curtains and raising the children, she was also in the process of “making.” Now, in her older age, she’s had a huge show at the Tate and is continuing to paint. I hope you will take a minute and look her up, watch some interviews on YouTube. She’s a treasure. And what about Abigail Thomas, who wrote a great rant on her Substack today! In film, I love Agnes Varda, who is no longer living. And, in closing, I want to say that I dropped out of college first semester and never returned. Yet I became a teacher. I became a mother and a grandmother. I learned film from my husband who dropped out of high school, yet he is the recipient (along with me) of many awards (Emmys, DuPont Columbia, Academy Award nomination, etc.). In the end, what matters is your passion for your art and your loved ones. And if you can teach some people along the way, that’s good, too.