Editor’s Note: The following keynote was delivered on June 13, 2025, at the NonfictioNow conference convening in South Bend, Indiana, and hosted by the University of Notre Dame’s creative writing faculty in collaboration with members of the Board of NonfictioNow. We recommend that you listen to the author read the address while you read along. The images throughout the text were projected on a screen during the address and are reproduced here at the same intervals. In this way, we hope you will experience some measure of the magic of the performance. Thank you.

Author’s Note:

This keynote was delivered on June 13, 2025, at the NonfictioNow conference convening in South Bend, Indiana, and hosted by the University of Notre Dame’s creative writing faculty in collaboration with members of the Board of NonfictioNow. I opened that in-person performance by acknowledging the privilege of time and space that is a keynote, and of my getting to share that space with phenomenally great writers like Kiese Laymon and Camille Dungy. I also thanked my numerous hosts for their inspiration and the gift of their work as writers and pedagogues. Like all of our work in this world, the keynote emerged from and responded to a historical moment that is ongoing, and I’d commented at the outset on the fresh violences that had continued to be carried out by the current administration, including just the day before the event, on June 12, 2025, the assault on Senator Alex Padilla by armed agents when he tried to ask a question of Homeland Security Secretary, Kristi Noem, at a news conference on immigration in Los Angeles. Having seen the video of that use of force against an acting government official the night before, I decided in that moment to dedicate my presentation to Senator Padilla and to the tears that he struggled to choke back. The particular use of the bodies of his assailants against him as they wrestled him to the ground—three armed men to one unarmed man—the positioning of their bodies reminiscent, to me, of the violence enacted against George Floyd—led me to wonder aloud about two things relative to Senator Padilla’s assailants: the phenomenon whereby one group of humans become specialists in subduing other groups of humans; and the question as it applied to my talk of whose call or what call those trained in this way are answering when they violate the rights of fellow humans. Whose call are they answering, how do they answer it, and why?

Preamble

It’s been so many years and numerous national and global crises later since Patrick Madden’s 2019 phone call inviting me to keynote in New Zealand—the dream-invite—that morphed into a low keynote delivered from the precincts of my living room in Providence, Rhode Island, that I really just want to start with the simple acknowledgement of our still being here, in this world, making our art.

Most essayists know something about choreography—how the play of the intellect is a dance—but the proper stage for such embodiments (with or without a pandemic) is often in short supply. That when we ascend a podium, and especially depending on how our bodies are gendered, raced or classed, we attempt to “move freely in [our] exposed isolation,” to quote Henry James.i We know that the only way to experience a polyphony of points of view is in the shared physics of an actually occurring present, which is another way of saying, in person. That an elan vital—an all caps collective joy—attends the most lively thinking at a core, even if it is a joy underwritten, just now, by sorrow and upheaval.

“To hold on to connections across a multitude of isolations.”This beautiful directive came to me from David Carlin as we tried to imagine what or who a beamed-in keynote in 2021 might serve. What I couldn’t have known until I’d written it was the extent to which today’s (high)keynote would be a reply to David’s years’ old but still relevant infinitive: “to hold on to connections across a multitude of isolations.”

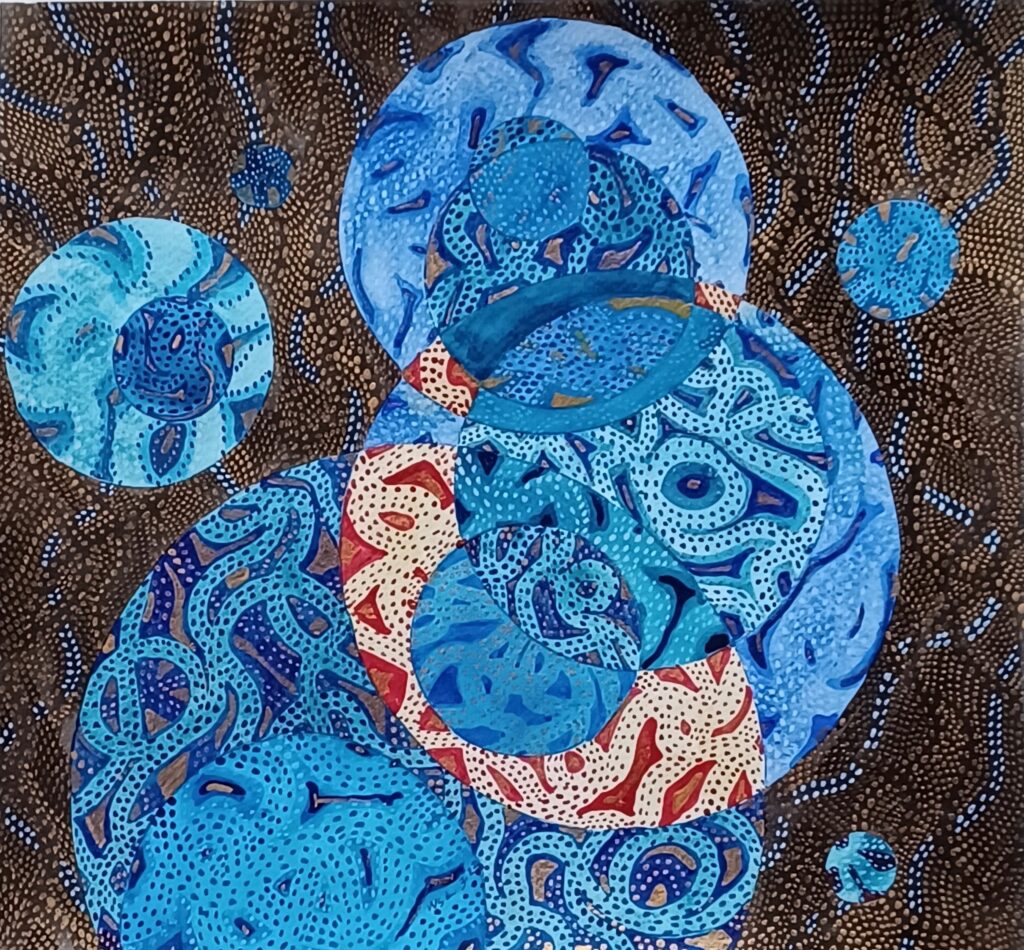

Today I want to address the importance of our serving as tethers to each other and to ourselves. I’ll beg your patience as I arrive at my ostensible focus—I’m an essayist after all—my focus: the terms by which we call and are called, name and are named, the question that each of us must ask ourselves of whether we return the call or ignore the call as writers and humans. I can’t arrive at the call without recourse to the unconscious and its myriad filial undergrounds;the unconscious as the place from which those calls issue and to which they productively return; the unconscious in the way that I maybe understand my friend, the painter, Wendy S. Lewis to have embodied it in these dot paintings—the many hundred painstaking canvases marked by watercolor and ink and more or less hovering around 12 by 12 inches whose callshe has felt compelled to fulfill for at least fifteen years, not knowing, she says, where they come from, significant departures from her life’s work as a landscape artist and portraitist. For me, the paintings offer the most apt image for the unconscious, a cross between inner anatomy and outer astronomy.

Figure 1. Wendy S. Lewis, “Astrobiology 2022 #5,” watercolor and ink, 11” x 11”.

A few clarifications before I start: Most of my inspirations are referenced herein, but two sources that don’t get direct mention are a book that I really love that I’ve read, re-read, and taught in courses on dream and nonfiction, Sharon Sliwinski’s Dreaming in Dark Times: Six Exercises in Political Thought and Darrin M. McMahon’s Divine Fury: A History of Genius

And speaking of genius, in addition to Wendy’s work, my writing partner of many years, Karen Carr’s visual art also appears herein, as well as that of my mom, poet-painter, Rosemary Cappello. Now, if we were in Italy—but we’re not, we’re not in Italy, we’re in South Bend, Indiana—but if we were in Italy, we would take espresso breaks between each section of my tri-partite talk. We would go away for a few hours, have some espresso, wander back, and be ready to listen again together, but we’re not in Italy and therefore I’m going to be reading straight through without pause, and I’m going to close with a segment titled “help me, help us, help me,” from my most recently completed book, Frost Will Come: Essays from the Bardo, a book that dictated itself to me following the death of my mom in September, 2022, and the sacred witness of caring for her in the many months before her death when my partner Jean and I answered the call.

Nonfiction’s Underground

composed

in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,

renamed Rhode Island in 2020,

in the northeastern region of the coastal United States

located on the traditional homelands and waterways

of the Narragansett Tribal Nation

and of other Indigenous Algonquin-speaking peoples—

the Wampanoag, Pequot, Nipmuc, and Niantic,

original stewards of these lands,

past, present, and always

Part One: Exegetical

Watching and reading Hannah Arendt, I am often captured by the sense that

there exists something she will not give up: something precious, mysterious

even to herself, but very strongly present. But isn’t that just the point of all of

this? She might say now, chin resting in her smoking hand from her place in the

bar in the underworld where the lost angels of the last century gather at dusk.

That we are unknowable even to ourselves, maybe especially to ourselves and

yet capable of collective miracles? Isn’t that what you must fight for again now?

—Lyndsey Stonebridge, We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt's

Lessons in Love and Disobedience, 12.

“Nonfiction’s Underground”: The furtive; the unseen but life-giving; the buried or forgotten; the place without light from which things emerge into the light; the purposefully hidden, the politically (clandestine); the psychologically off-limits. I’ve come here today to ask what would happen if, as nonfictionists, we took seriously a charge reiterated by some of the most important thinkers and writers of a previous generation, from Toni Morrison to Judith Butler, from Václav Havel to Angela Davis and back again:

that political change doesn’t happen without psychic change.

No conscious reform without great unconscious resistance:ii

the unconscious that animates every threshold and is a threshold, that is art’s driver, that we ignore at our peril: a fertile underground, to be sure—it is never vanquished, just like the self I knew chemotherapy could never touch no matter how it altered me. Everything you’ve ever experienced is stored there—whether you believe a great twentieth-century essayist or a great nineteenth-century one, whether you move to the groove of Sigmund Freud or Thomas De Quincey who said the same thing differently, and remember, Freud had famously said, wherever I have been a poet or philosopher has been there before me: “…in mental life nothing which has once been formed can perish—that everything is somehow preserved and that in suitable circumstances (when, for instance, regression goes back far enough) it can once more be brought to light.”iii

How can our own inner sleeping giants or inner inklings be stirred? What will it take for the not yet to turn now?

When Louise Glück said she looked for the habit that characterized one of her books and sought in the next one consciously to break it, it was the unconscious element of her work that she was aiming to notice in order to incite a literary imagination of the more and more possible.

When a swath of a country’s populace votes for an ill-equipped, crazed, and dangerous president, it is really a vote against the first woman of color to claim the authority of the Oval Office, fully to “reside” and “preside” there; a collective sexist and racist unconscious is at play. It’s a vote as reaction formation and its bases are deeply disguised, hidden to the voter, even if the voter might boldly claim these are the very reasons for his vote. Our reasons are undergirded by an unconscious that the literary imagination is interested in charting and activating and bringing to light, that motivates our every act and choice and desire, granting access to, or by the same token, barring us from our capacity for moral conscience.

“This is a disinhibited electorate. It is no longer, on the whole, frightened of its own worst impulses” (italics mine).iv I’m not sure if all autocracies emerge under the sign of the unbridled, the brutish, the libidinal, and the infantile (or, in the terms of our own, the mendacious and the craven); what’s clear is that they usually evince a trait in common: the cruel. Trump’s perverse gift was his being able to tap into what I’ll call a collective unconscious, a political unconscious, gone awry, shared by many of our fellow men in which Thanatos, the drive toward death, came, for the time being, to gain ascendancy over Eros—connector, creator, lover. In a small volume that I love on the lecture (as nonfiction) written approximately one hundred years ago by a fellow named Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (aka “Q”), he implores:

The truth I mean is this, –that when a number of persons are met for a purpose

in itself unselfish (and the love of learning is that) there often prevails over the

assembly a strange congregational spirit, recognizably good by any individual

member, yet not his own, yet nothing he consciously brought; but unlocking,

rather, some sense that [people] have more good in common than they pretend

to, if only some other [person] have the gift or art to unlock it.

The writing and teaching and reading we do as nonfictionists unlocks; Trumpism unleashes. We don’t say, “Let us work on unleashing love and kindness.” We reserve that operation for anger, rage or fury.

An inner ogre is unleashed; an inner “aha” is unlocked.

Unleashing is a feature of human impulses; unlocking is a feature of human thought.

As one thing is solved, another thing opens; a part finds its whole, a surface, its depth, a shape, its shift, and so on; unlocking requires patience, subtlety, and, in place of a shock that paralyzes, a metamorphosing surprise that mobilizes.

Can the unconscious be recuperated? Reworked? Rearranged? Differently furnished? Can nonfiction supply the ailing unconscious with restorative objective correlatives? The MAGA movement, among the many needs it seems to have met for the people who were seduced by it, gave its members a feeling of belonging to something greater than themselves and for which they needn’t take responsibility. In psycho-analytic terms, it gave them something to cathect to; it supplied their unconscious rage not just an “outlet” but a legitimating fetish, an icon and an iconography that needn’t be translated into rational terms or art or any of the things we writers rely on in order to live among one another with grace and care. Objective correlatives (T.S. Eliot’s term) are the necessary tethering devices—the external conduits to our internal unconscious needs and desires—that any person needs to make meaning of their lives, and the more nuanced, the more they serve as bearers of finely tuned pluralities, the better. Fetishes rely, on the other hand, on overvaluation of one thing—often in the form of a slogan—to the detriment of all others; on symbol adoration and idolatry; on monoliths; the erasure of the work required to make meaning; and an ossification of thought. If objective correlatives are gifts we share with one another, in the form of writing or art, fetishes are the things we kill each other over in the form of war. Under the sign of a hyperbolic symbolism, the “object” to which a fetish refers (like a flag, for instance) stops being itself; in the realm of art’s reworking of an objective correlative, the thing becomes more itself, an embodiment of its invisible essence.

“O, sleep, o gentle sleep/…Chief nourisher in life’s feast” (Shakespeare)v

Sometimes I find myself wondering how “they” sleep at night (you know who I’m talking about); which is another way of asking, how do they live with themselves? One answer to which might be that they don’t. Trump is known to require only four to five hours of sleep—he brags about how little sleep he gets as he rage-posts mid-night, dubbing his opponents so many “sleepy Joe’s”—but experts note Trump’s numerous episodes of “daytime somnolence” and his habit of (reportedly) consuming twelve Diet Cokes in the course of a day. Short sleepers, also known as the sleepless elite, include Margaret Thatcher, Hitler, and Stalin. Such people are not insomniacs—people who want to sleep but can’t; rather, they refuse to sleep out of a constant need for vigilance. Sleep makes us vulnerable, not only to strangers, but to ourselves. Trump’s problem (and maybe Musk’s too) is that they don’t get enough sleep, leaving the rest of us to be kept up by their daymares.

Why would anyone claim sleep over wakefulness (wokeness) unless they were very, very tired, so tired that they’ve become intolerant of the promises that imagination affords, so tired that they no longer dream and therefore no longer think, so tired that fear takes hold and hate invites them to defend themselves at all costs, so tired that they are vulnerable to their own misunderstood unconscious impulses through which they perceive everything and everyone as an enemy in need of conquest?

If strongmen the world over have argued for less sleep, figures like Gandhi and Einstein argued for more,vi which puts me in mind of Jonathan Crary’s 24/7, where he tells of the State Department’s interest in studying migrating birds that stay awake far beyond any human capacity in the hope of being able to create a type of “sleepless soldier”; he describes how sleeplessness creates worlds that “radically exclude the possibility of care, protection, or solace.” He worries about people who wake themselves up to check their messages. He boldly concludes that sleep is the “only enduring ‘natural condition’ that capitalism cannot eliminate.”vii

Perchance, to dream. . .

Michel Foucault: We all know him as one of the great articulators of the forms that power takes in human life, coiner of microagressions, genealogist of sexuality, and where nonfiction is concerned, lambaster of straight-up confessional narratives bent on redemption. But Foucault, one of psychoanalysis’ most ardent critics, began his career writing about dreams and dreamwork, and turned back to dreams again at the end of his life where he found in the incubation rooms of the Ancient Greeks a model for the type of self-reflection that human ethics depends upon, with emphasis on what he called “the care of the self.” We could if we had time, but we don’t, embark on a seminar together whose aim might be to distinguish between the self-awareness that undergirds ethical regard of one another, and self-regulation, self-management (see cell phones and social media), self-consciousness, fill in the blank, as they operate in our moment and in our work.

Dreams: Those transvaluations of the remains of the day, those thought montages assembled under cover of night.

Figure 2. Karen Carr, Photomontage, 2023-2024.

Dreams try to give form to the unbearable knowledge and intolerable realities of our lives. As alternative worlds that we carry within us, they are no less real than our flesh and our blood—they are the worlds made manifest in literature. To every dream, according to Freud, its unplumbable navel: the uninterpretable origin that knows neither beginning nor end, but that the creative among us are drawn nevertheless to follow.

To every essay, its awesomely inarticulable pivot point; its jolt, gasp, pause, or means of arrest. To every essay, a Barthesian punctum, the highly subjective detail even in a seemingly banal photograph that pierces you and tells you you’re alive. To each essay, a phrase, sentence, or paragraph indicative of its unplumbed center—the reason for the essay’s having emerged in the first place, that often enough remains undeveloped or untapped, like the mercurial compressions of our dreams.

One such cluster captured me from an essay by Freud, “On Dreams” (1901). He’d been blithely describing how the stuff of the unconscious is “allowed to prance about,” as the mind gives itself over to the most lively animations, while simultaneously suppressing actual motor activity in the sleeper and by all means guarding her from the need to wake up. Then he paused briefly, powerfully, to offer a tantalizing suite of exceptions to this rule:

We must in any case suppose. . . that this guard [against sensory stimuli] may

sometimes consider waking more advisable than a continuation of sleep.

Otherwise, there would be no explanation of how it is that we can be woken up at

any moment by sensory stimuli of some particular quality. As the physiologist

Burdach (1838, 486) insisted long ago, a mother, for instance, will be roused by

the whimpering of her baby, or a miller if his mill comes to a stop, or most people

if they are called softly by their own name.viii

Do you want, like me, at this point to stop reading the essay, and instead, as the song lyric goes, “follow follow follow” these three examples toward some luminous end? Sleep might be broken by the hunger of another being who depends upon us for nourishment; by the break in the reassuring hum that we depend on for subsistence; or by the act of being called softly (as in caringly) by our own name. What co-union is conjured by this last example? To what or in what direction are we being coaxed by the calling of our names?

Does it matter what we call it? (Name it?—creative nonfiction, lyric nonfiction, lyric essay—I once devoted an entire keynote to this question)? But this name, the name by which we as humans are called—this is different: the sign by which we are called into being; called to be distinguished, one from the other; called to voice by a voice not our own—the voice we look back at, and to which we respond, “here; present”—each name, your name, my name, a kind of eternal “yes” that follows us from the beginning to the end, that came from the other to you. This sound that we were given, by which we would ever after be “called.”

Given name, dead name, name yet to be: Who is it who is calling your name? There was the mouth of my cat who, according to her sitter, enunciated, “Maaaaaarrre—reee, Maaaaaarrre—reee,” as she ran to look for me at the top of a stair. A name is a conferral; it’s never implicit, yet it comes to bear an uncanny at-oneness eventually with the person it names, which doesn’t mean we embrace the names conferred upon us by oppressors; we reserve the right to change our names and claim our names.

Yet, in foregrounding the power of being called by our names, I don’t mean to reify the name as an assertion of our individual, sovereign identities or egos; I’m thinking instead of the name as the sign that marks both our difference from and connection to others: I promise to call you (address you) just as I promise to answer when you call my name if and when I am called to care, which is the same thing as being called to write.

In his essays on the characteristic features of totalitarianism and how we might resist them, the Czech writer and dissident, Václav Havel, describes how, eventually, the system becomes faceless: “The automatic operations of a power structure thus dehumanized and made anonymous is a feature of the fundamental automatism of this system. . .” Under totalitarianism, humans must conceal themselves behind “a ritually anonymous mask in order to have an opportunity to enter the power hierarchy at all.” [italics mine]ix Václav Havel, Alexei Navalny, Czesław Miłosz, all of them confirm the making anonymous of moral conscience—in other words, a namelessness—that the state depends upon at its most oppressive.x

“Pronounce your name in dreaming state. It will elate the angel who directs your fate.”

“Pronounce your name in dreaming state. It will elate the angel who directs your fate.”

“Pronounce your name in dreaming state. It will elate the angel who directs your fate.”

Sometime in graduate school, my partner, Jean, spoke this poem that had come to her in the night into my ear, and I’ve experienced it ever since as the line of an essay waiting to be written. We can’t just call our names or be called by them; we need to pronounce them in a realm out of reach from the ordinary; they might require our own enunciation, spirit self to material self, inner voice to outer, with the effect, according to this dream poem, of inciting incipient joy.

Is each person’s angel, her anterior self, her sixth sense, her “genius” in that Ancient Roman sense before the word restricted itself in the Age of Enlightenment to “individuals of exceptional intelligence”? Genius, whose root-sense is genera/life-giving, is something all people come into the world with, a “guardian deity or spirit [who] watches over each person from birth,” a demon, actually, in the Platonic sense, the “angelic ‘messengers’ who ‘shuttle back and forth’ between the gods and men, or spiritual beings who were themselves ‘a kind of god,’ existing ‘midway’ between the human and the divine.”xi The very figures whom Socrates was accused of unleashing into the city in the form of ideas, and to which he martyred himself.

In a lecture delivered at Warren Wilson College titled “On the Plausibility of Dreams,” my friend Charlie Baxter quotes a famous Robert Bly poem called, “The Teeth Mother Naked at Last,” a poem about all the political lies that are fit to print, in order to emphasize a line that only came into the poem in a later version, the question: “What is there now to hold us to earth?” Those who don’t care about the earth, are trying to float free of it, Baxter explains. Our current leaders are drifting toward death.

Dream is sleep’s tether even though it relies on drift and alterity.

The call is another tether. As are our names.

In order to resist the current order as nonfictionists, I think we need to tether ourselves both to the earth and to its undergrounds, to the unseen and the unheard within us, and in that process, to each other.

Part Two: Appositional/Notes from Underground

Figure 3. Cover of Highlights Magazine from 1962.

In November, 1962, twelve-year-old Jonnie Pratt of Riverview, Michigan writes to the editors of Highlights magazine: “When something slips away from your mind, where does it go? I would like to know the answer.”

The Editors replied,“I think nobody knows when something slips away from your mind where it goes.”

*

No two generations’ unconsciouses are alike: my ten-year-old niece’s will be populated with googly-eyed avatars and squishies, accompanists to learning, the illuminated figures with whom she exchanges knowledge for coins.

*

As a child in Tucson, Arizona, Susan Sontag was known to bury herself in a hole that she dug, six feet by six feet by six feet. She made a shelf for a candle, but it was too dark in there to read.

*

My mother once told me that they never put their lost teeth under their pillow and waited for money to appear. They were poor after all. They put their teeth into cracks in the side of their house. The teeth were always there, and she’d often re-visit them.

*

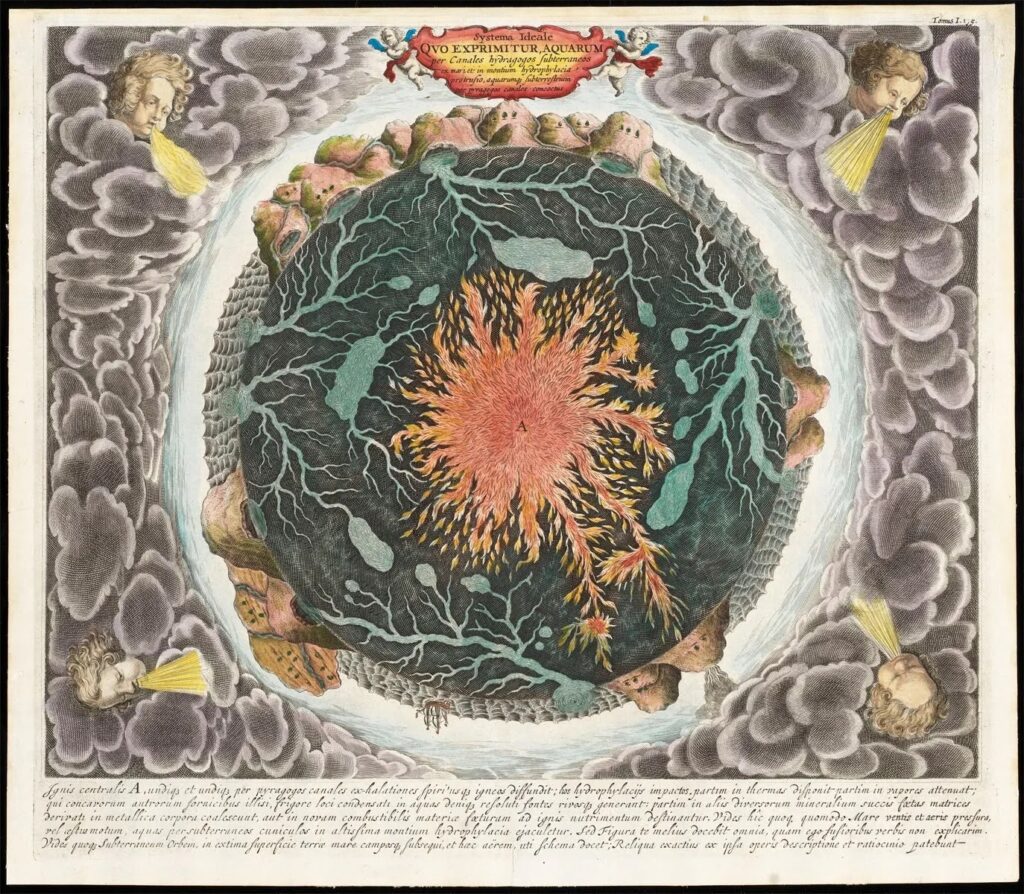

Figure 4. Athanasius Kircher, Mundus Subterraneous/Subterranean World, 1678, subterranean waters, turned into hot springs by contact with subterranean fire.xii

Directive 1: Make a book out of your own “notes from underground,” that always operative ever-flowing, inaccessible reservoir, the inner core of consciousness that, like the iron-nickel amalgam at the center of the earth, creates (!) the very magnetic fields that orient our atmosphere, of negative and positive ions, of affects, and gravitational zones, the what that we are drawn to and the who.

*

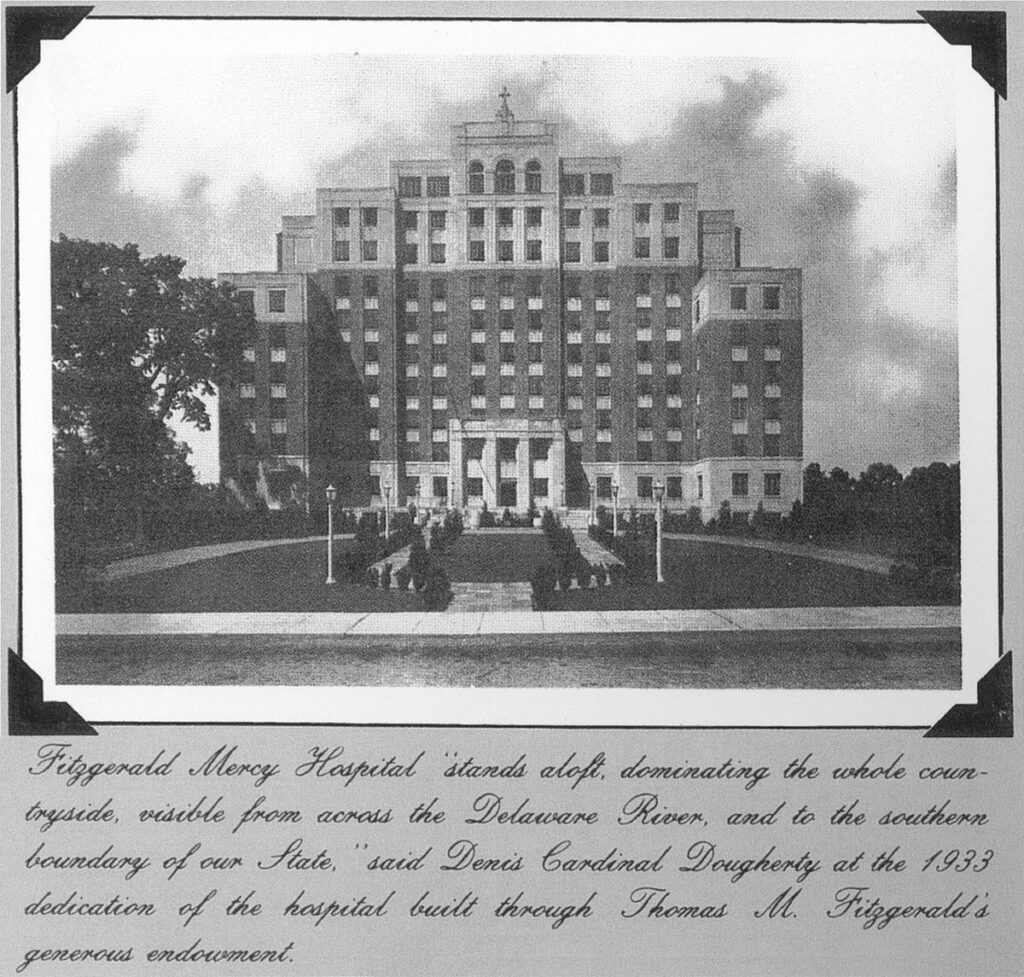

Figure 5. Fitzgerald-Mercy Hospital, Darby, Pennsylvania.

On the edge of sleep—there’s no way to explain it so I’ll need to find a way—how the faces of each and every fellow cleaning woman vividly appeared fifty years forward of our having worked together at Fitzgerald-Mercy Hospital in Darby, Pennsylvania. One summer in my teens, I joined the invisible brigade in the hot, dark spaces of the hospital’s underground where we’d collect the cart assigned to us, then gather the stash of rags, soap, and toilet paper that we’d need for the day. When the supervisor reassigned me to Intensive Care, I was supposed to understand it as a promotion. I was just a teenager, but she consigned me to the death chambers of strangers; for hours on end, my job was to dust the surfaces of breathing machines, a free ticket to rooms so sterile, there was nothing to clean. My new role cut me off from the social encounters with fellow female workers that had been the high point of the job. Peg, Patty, Eunice, Yvette, Charlie short for Charlene, I remember how you hugged me when I left, and said, “Go on now, go make somethin’ of yourself, little Mare, ya hear?”

*

“With the help of the telephone, [we] can hear at distances which would be respected as unattainable even in a fairy tale. Writing was in its origin the voice of an absent person. . .” xiii

*

Twice in my mother’s final days she called me from the hospital bed on her cellphone—I have

no idea how. I’d be in the lobby and on my way up; I’d be in her apartment washing a dish she would never eat on again. “Hi Mom. Is everything ok?” I’d say, “I’m literally on my way over.”

And she’d say, “I just want you to know that I love you.”

“I love you too, Mom.”

Then she’d add an emphasis, “I love you very, very much.”

*

In the attention economy, I communicate with everyone and no one.

To recreate nonfiction in the form of an earlier telephony.

*

How I call out to my absent mother when I’m sick and after she’s died: Mom, help me; mom, where are you?

How George Floyd called for his mother as his breath was being taken away;

How gay makeup artist Andry José Hernández Romero called for his mother when a Salvadoran prison guard shaved his head and stripped him of his clothes.

*

Name one of your personal unfathomables and consider how to plumb its depths. For me, the gifting of the golden pager to Trump by Netanyahu: behold this memorial to maimings of people’s fingers, hands, and eyes.

Figure 6. Golden pager gifted to Trump by Netanyahu, February 4, 2025.xiv

*

“For reasons that remain mysterious. . .every 100,000 to a million years or more, the north-south orientation of the magnetosphere reverses, an event often preceded by an overall weakening of the field.”xv

Figure 7.Artist’s rendering of Earth’s Inner Core, Rostislav Zatonskiy/Alamy.xvi

*

“. . . linked by a system of underground channels…[trees] perceive and connect and relate with an ancient intricacy and wisdom that can no longer be denied… when I followed the clandestine path of the conversations, I learned that this network is pervasive through the entire forest floor, connecting all the trees in a constellation of tree hubs and fungal links. . .[comprised of] chemicals identical to our own neurotransmitters.”xvii

Figure 8.Karen Carr, Photomontage, 2024-2025.

*

“A number of people are able to recall an experience in their childhood in which they were visited by some special being who blessed them, cursed them, advised them or called them…Benign visitations seem to mark the achievement of a precocious self-awareness…”xviii

*

Please, can someone call me to the page? Call me to the word? What word?

Please, can someone call me to the page? Call me to the word? What word?

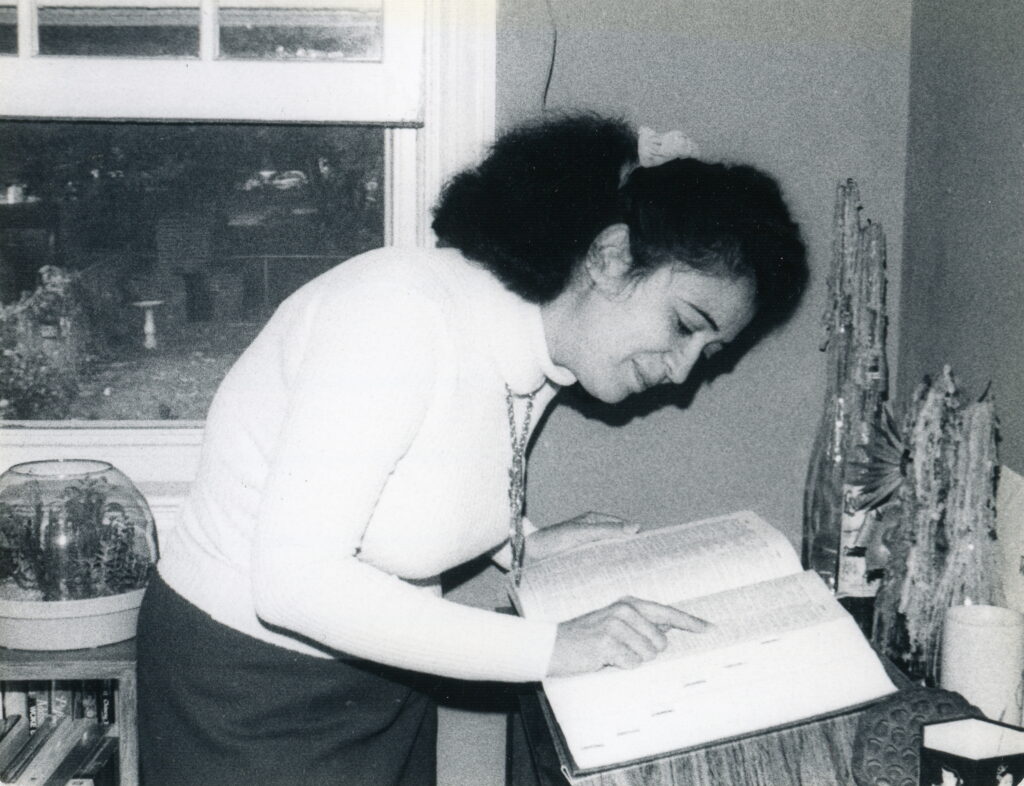

Figure 9. The writer’s mother, Rosemary Cappello, set before her beloved dictionary, circa 1972, in the corner of their row home where she read and wrote. (Photo Credit: Frances Brown)

*

The [earth’s] inner core appeared to be spinning slightly faster than the planet’s outer layers; now it is spinning slightly slower.

*

When we die, our spirit selves’ energy our life force (?) our anima moves through a tunnel at the speed of light and repopulates (pollinates?) all still living things and still-to-be-things in its path. This is not reincarnation; nor is it incarnation. It is carnation. I imagine in the aftermath each of us comes out smelling of cloves and rippled along the edge, striated in pink or red, incarnadine.

*

The call for our earliest caretaker is the first call, a searching call that doesn’t know a name but cries in the direction of a face whose answer it later names “mom.”

Figure 10. Mom at her typewriter. (Photo Credit: Frances Brown)

*

Seismic data [now] indicate that nested within the inner core is another distinct layer they call [get ready] the innermost core.

Figure 11. Wendy S. Lewis, Astrobiology 2023 #3, watercolor and ink, 9″x12″.

*

M. Gessen: “In the 1990s, Kosovo Albanians responded to the Serbian regime’s forced takeover of their education system. . .[with] a parallel underground school system. . .[that] met in boarded-up storefronts.” The current prime minister, Albin Kurti, trained there.xix

*

When the dying person emerges from a deep state of unconsciousness to bouts of sudden, inexplicable presence to the people in the room, they call it “rallying.”

*

M. Gessen: “In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Polish dissidents operated what they called a flying university in apartments across the country.” Its students were “the people who went on to build the only post-Communist democracy that, so far, has been able to use electoral means to reverse an autocratic attempt.”xx

*

At the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow, Russia, in fall of 2001, Jean and I lived the open secret of our sexuality in an unfamiliar land, pulling our single beds apart in the dorm each morning and pushing them back together at night.I was teaching Tender Buttons, and Jean was teaching Tami Gold’s Juggling Gender, a film about a bearded lesbian circus performer named Jennifer Miller, when one of our students said she needed to take us somewhere but she could not say where. We journeyed in relative silence from metro to bus before arriving at the end of a very long walk at a classically nondescript high-rise, one of whose apartment’s housed the gay and lesbian underground library. The director could lose her job or be sent to Siberia. Thus were the stakes of this furtive reading room with the kitchen that sheltered, importantly, a Xerox machine. Her English was about as good as our Russian, so Jean interviewed her in French. Mostly, I remember the way she handled the books like the lovers who’d made so many journeys in different languages, now safely stowed in a palm, waiting to be opened, secretly kept.

*

From a letter from my mother, November 15, 1998,on the occasion of my first book, Night Bloom:

Dear Mary,

On the way home on the train, I started to read your book and it seemed like we

were home in no time. Once home, I read more until it was just too late to stay up.

It was near three when I went to bed and I couldn’t sleep. I was too tired to get up

to finish reading, to write to you, so I just lay there.

I finally fell asleep around five and woke up three hours later, thought if I had

breakfast perhaps I could sleep some more, but I finished reading your book

instead.

…When it is over, it is not over.

Part Three: Self-reflexive

Help me, help us, help me,” from Frost Will Come: Essays from the Bardo.

I touched her, I talked to her; but it was impossible to enter into her suffering. . .I was

terrified by the idea that the pain might have started in the morning, when Maman

had no one with her and no means of calling anyone. . .

Would Dr. P keep his promise: ‘She shall not suffer’? A race had begun between death

and torture. I asked myself how one manages to go on living when someone you love

has called out to you ‘Have pity on me’ in vain.

–Simone de Beauvoir, A Very Easy Death, 81, 58.

She can’t hear you, I had repeatedly to tell people; she can’t see you; you shouldn’t put that IV feed into her right abdomen—she has scar tissue there and discomfort from when she had the drain installed those many months ago.

“Thank you for telling me; I’m glad that you’re here.”

Even on your deathbed, you need an advocate.

I really do think that the hospice staff did all that they could to “make my mother comfortable,” though I can also imagine a reader of these pages thinking that my mother was done wrong. Can we accept that dying might entail suffering beyond the reach of medication? That dying opens the floodgates for scenarios that are far from “routine,” that are nearly impossible to bear, though for different reasons and in different ways for the patient than for those who love her?

In the severest hours of my mother’s need, I attempted extrasensory perception. During periods of “terminal agitation,” or when waiting for the medication to ease ripples of pain, I held my mother’s hand and visualized a scene, then tried to “send” it to her through my fingers. I imagined a stream flanked by flowers of all variety and hue, her favorites of course: peony and coxcomb, gardenia and orchid, roses, azaleas, geraniums, violets, and the very little ones, the Johnny jump ups. I imagined that she was floating down this flower-bedecked stream on her back, eyes to the sky and palms open in a state of perfect clarity, beatitude, and calm. Was it my transferential dream that calmed her and bade her sleep or a narcotic cocktail they’d just flooded through her veins? I liked to think that I was helping her, but I knew my help only went so far.

Figure 12.Paintings by Rosemary Cappello.

One day upon my arrival at her room, I found her saying “help me” over and over again. Her eyes flashed open, and she said my name, but it wasn’t clear if she understood that I was I or the Blessed Mother Mary. For some reason, I thought that if I’d invoked the image of floating that I’d carried out silently before, it might help her. I told my mother I was carrying her and that we were floating down a stream. Not only did this not mitigate her state—I had asked her where it hurt, and she’d replied, “everywhere”—but my suggestion that I was in the stream with her simply inspired a different version of her prayer. Now she implored the invisible presence in the room, “help me, help us, help me.”

Figure 13. Karen Carr, Photomontage, 2024.

No matter how punishing this process was, I could never have foretold the episode that unfolded next, an episode whereby the unbearable came to be overlaid with the unbelievable.

Occasionally, I would check my mother’s cellphone to see if she had gotten any messages from people who did not know where she was. I saw that she was texting with a pizza parlor down the street from where she had lived.In weeks prior, they had sent texts saying the pizza she ordered was on the way, and she responded, “can’t wait,” and “yay.” Today, however, was different.

Tuesday, August 30, at11:09 a.m.

Member Flash Sale Alert!

Click below and check your wallet for a mystery discount.

Offer expires in 24 hours so get moving!

The text, evidently, had not come from a person but from a bot.

Tuesday, August 30, at 3:03 p.m.

My mother, perhaps accidentally or perhaps not, sends an emoji of a puppy with its head exploding and an incomprehensible text:

No g hall no oh hi by xzzszzxxcccvvvvvvvvfcc.

Someone (or was it something?) replies to this, saying:

Hey there! How can I help you?

My mother does not reply.

On the same day, August 30, at 5:57 p.m., she texts:

Vbbp

I can’t get up.

They respond, again, with what must be an auto-reply:

Hey there! How can I help you?

She says:

Please help me heft up

They ask:

How can I do that?

She says:

Help me get up.

They say:

Ok give me your arms.

She says:

My name is Rosemary Cappello

Can someone help me?

They say:

How can I help you?

She repeats:

Help me to get up.

And there the exchange ends.

Is there an emoji that can convey a combination of heartbreak and rage? When I see this on my mother’s phone on Wednesday, August 31, at 2:33 p.m., I write:

Please stop sending messages.

My mother is in hospice

and did not know who this was from.

They reply:

Heard. You are unsubscribed from our list!

I write (but why I write this I don’t know):

Thanks so much!

I will never know if this harrowing correspondence was authored by someone “real.” I know that my mother was real, and that they kept up a pretense of help even when my mother’s utterance of her name should have lent an incontestable veracity to the exchange, making it hard to turn away. When I wrote back, they said, “heard,” which is right up there with so many other wimpish abbreviations in this age of quick fixes and quick exits (my least favorite being “same”!).

In the midst of the depths of my mother’s “help me’s,” I happened to use the word “suffering,” as in “I wish my mother could be released from her suffering,” with the wisest, kindest hospice nurse on the ward who I’ll call “M.” I can’t remember exactly what she said, only that she took issue with my use of the word, “suffering.” No one suffered on her call, I heard her say; suffering was something they simply did not allow. I did not say, “Help me, M.! Please! Help us!” I knew that she could not; I knew that what cannot be helped must be endured. Etymologically, suffer means to endure, but also to bear. It means to carry, or to be made to carry. Pain is something you ameliorate. And, mostly afterwards, forget. Suffering is something that continues, but for M., the emphasis was on the sense of something that you allow to continue (as in “to suffer fools”). With pain there is agency; with suffering, there is not. “Help me” is a phrase addressed to someone, some other, who the person in pain believes exists.

What I really should have said was that my mother was in agony, in the way I had written to my friend, Karen, on September 10th of that year, “It’s been another harrowing 24 hours. When the drugs wear off, my mom is in a kind of agony I’ve never witnessed in my life.” This was the more precise word since its roots refer specifically at least as far back as its usage in the 16th century to the “struggle that precedes natural death.” Reaching further back, the “agon” are the people who gather to watch the struggle as in a wrestling match in ancient Rome. Spectatorship, if not compassionate witnessing (of extreme pain with the hope of victory) defines it at its core.

If suffering endures, our witnessing of it endures a thousand-fold, and we need to do something with that. When, long after my mother’s death, I find myself returning to these episodes in particular in my mind, a grief counselor I have been seeing tells me that my story about my mother’s “help me” texts are intrusive thoughts that are not, well, “helpful.” He wants the best for me; he’s trying to help me, and he does. But I want to tell him these aren’t intrusive thoughts. They are necessities that ask to be transmuted by my art; they need to be felt again and again until they can be properly seen, seen in a way that I can learn to live with.

Were these terrible episodes “helpful” in their persistence long after my mother had died? I’ve recorded them here; I’ve included them because nonfiction as a devotional practice hews close to things so true that they could not possibly be imagined. Here is a record of the veracity of human suffering. Make of it what you will; my mother’s iPhone has since been wiped clean. All data has been erased along with her name.

i I’m quoting Basil Ransom’s description of Verena Tarrant in Henry James’ The Bostonians, 263: “She moved freely in her exposed isolation, yet with great sobriety of gesture; there was no table in front of her, and she had no notes in her hand, but stood there like an actress before the footlights, or a singer spinning vocal sounds to a silver thread. There was such a risk that a slim provincial girl, pretending to fascinate a couple of hundred blasé New Yorkers by simply giving them her ideas, would fail of her effect, that at the end of a few moments Basil Ransom became aware that he was watching her in very much the same excited way as if she had been performing, high above his head, on the trapeze. Yet, as one listened, it was impossible not to perceive that she was in perfect possession of her faculties, her subject, her audience. . .”

ii Felix S.H. Yeng (2022) puts it succinctly in his essay on “Psychoanalyzing Democracies”: “…populist and fanatical political movements speak to much deeper psychological realities than what simple reforms in democratic institutions and public culture can address. Populist movements (whether of the toxic or progressive types) are resilient to conscious reform due to how they function as unconscious psychic defenses against severe anxieties for their participants. This means that unless the psycho-defensive nature of these movements is tackled, conscious reform will be met with great unconscious resistance.”

iii Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, 16.

iv Fintan O’Toole, “The Second Coming,” NYRB.

v I’ve juxtaposed favorite phrases—the first one, incantatory—from two separate Shakespeare plays that I suspect my readers will recognize: Henry IV, Part Two, Act 3, Scene 1, and Macbeth, Act 2, Scene 2, spoken by Henry the IV and Macbeth, respectively: “. . .O sleep, O gentle sleep,/ Nature’s soft nurse, how have I frightened thee,/ That thou no more will weigh my eyelids down, /And steep my senses in forgetfulness?” And, “Methought I heard a voice cry, ‘Sleep no more!/Macbeth does murder sleep’: the innocent sleep,/Sleep that knits up the raveled sleeve of care,/The death of each day’s life, sore labor’s bath,/Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course,/Chief nourisher in life’s feast.”

vi I’ve painted these portraits of sleep with a broad brush. Gandhi apparently followed the early to bed, early to rise dictum, but he slept for short periods throughout the day, and of course practiced meditation. Einstein was known to sleep for at least ten hours a day. Hitler’s relationship to sleep seems to have been complicated by his use of amphetamines. Stalin was known for calling meetings or summoning people to dinner at two o’clock in the morning, but would sleep a potentially decent number of hours thereafter starting around four a.m. The point, in part, is that no matter what their sleep habits were, strongmen seem to enjoy painting a picture of themselves as people in possession of the superhuman ability to continue working while the rest of us are sleeping, or of remaining vigilant while everyone else’s guard is down. Elon Musk’s habit of sleeping on the floor of his companies; of boasting about 120-hour work weeks for his employees at his “Department of Government Efficiency,” and of lining the halls of federal buildings with beds for these workers so that they could be called to work at any time of day or night is also a case in point.

vii Jonathan Crary, 24/7, 1-2; 8; 13; 74.

viii Freud, “On Dreams,” 168. Freud is quoting Karl Friedrich Burdach (1838), Die Physiologie als Erfahrungswissenschaft/ Physiology as an Empirical Science, vol. 3 of the 2nd edition. Burdach was a pioneer of neuroanatomy and a vitalist whose prolific studies of the structures that constitute the human brain influence medical understanding to this day. He is credited with the neologism, “psychiatry,” and among the first (alongside Lamarck and Bichat) to introduce “biology” into scientific discourse.

ix Václav Havel, “The Power of the Powerless,” 34.

x For another type of calculated anonymity under totalitarianism, consider Vladmir Putin’s refusal in public to refer to his major political opponent, the beloved opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, by name. It is chilling to watch footage of Putin on Russian TV find ways to cancel Navalny’s humanity by referring to him with the vaguest, most general of terms.

xi McMahon, Divine Fury, 17, 10.

xii Kircher’s Subterranean World, Wichita State University. https://www.wichita.edu/academics/fairmont_las/geology/wparcell/Kircher/Mundus/Index.php.

xiii Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, 38.

xiv Mick Krever, “Netanyahu gifted Trump a golden pager during their meeting in Washington,” CNN, February 6, 2025, figure 1.https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/06/middleeast/netanyahu-trump-golden-pager-intl.

xv Natalie Angier, “The Enigma 1800 Miles Below Us,” New York Times, May 12, 2012.

xvi Robin George Andrews, “Earth’s Inner Core: A Shifting, Spinning Mystery’s Latest Twist,” New York Times, January 23, 2023, figure 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/23/science/earth-core-reversing-spin.html

xvii Simard, Finding the Mother Tree, 5.

xviii Charles Rycroft, The Innocence of Dreams, 148.

xix M. Gessen, “This is How Universities Can Escape Trump’s Trap, If They Dare.” New York Times. April 14, 2025.

xx M. Gessen, “This is How Universities Can Escape Trump’s Trap, If They Dare.” New York Times. April 14, 2025.

*

With thanks to Nicole Walker, David Carlin, Patrick Madden, Paul Cunningham, Dionne Irving and the entire NonfictioNow team. Additional thanks to Jessica Hendry Nelson for the invitation to translate the originally embodied keynote into a form that could be widely disseminated, and to Matt Schroeder for all of your technical expertise and patience.

I’d like to acknowledge the following interlocutors, without which, there is no keynote:

Bibliography

Andrews, Robin George. “Earth’s Inner Core: A Shifting, Spinning Mystery’s Latest Twist.” New York Times, January 23, 2023, figure 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/23/science/earth-core-reversing-spin.html

Angier, Natalie. “The Enigma 1800 Miles Below Us.” New York Times. May 28, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/science/earths-core-the-enigma-1800-miles-below-us.html.

Butler, Judith. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Chang, Kenneth. “Scientists Detect Shape-Shifting Along Earth’s Solid Inner Core.” New York Times. February 10, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/10/science/inner-core-earth-shape-change.html.

Crary, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. New York: Verso, 2013.

Davis, Angela Y. “The Truth Telling Project: Violence in America” (2105), 68-74. In Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

Davis, Angela Y. “Political Activism and Protest from the 1960s to the Age of Obama” (2013), 88-98. In Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

de Beauvoir, Simone. A Very Easy Death. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1964.

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium Eater. New York: Penguin Classics, 2003.

“Donald Trump: Sleep, Schedule, Somnolence” @ Dr. Zebra: Medical History of American Presidents. https://doctorzebra.com/prez/z_x45_trump_sleep_g.htm.

Foucault, Michel. “Dream, Imagination and Existence” (1954), 31-80. In Michel Foucault and Ludwig Binswanger, Dream and Existence (Studies in Existential Psychology and Psychiatry). Edited by Keith Hoeller. Translated by Forrest Williams. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press International, 1986.

Foucault, Michel. Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984, volume 1. Edited by Paul Rabinow. New York: The New Press, 1998.

Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and Its Discontents. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961.

Freud, Sigmund. “On Dreams,” 142-172. Edited by Peter Gay. The Freud Reader. New York: Norton, 1995.

Gessen, M. “This is How Universities Can Escape Trump’s Trap, If They Dare.” New York Times. April 14, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/14/opinion/trump-higher-education.html.

Havel, Václav. “The Power of the Powerless,” 1-80. In John Keane, Václav Havel et al, The Power of the Powerless: Citizens Against the State in Central Eastern Europe. Edited by John Keane. Translated by Paul Wilson. New York: Routledge, 1985.

James, Henry. The Bostonians. New York: The Modern Library, 1956.

Kircher, Athanasius. Mundus Subterraneous/Subterranean World (1678). Book IV. Pyrography, or the origins of underground fire. Kircher’s Subterranean World, Wichita State University. https://www.wichita.edu/academics/fairmont_las/geology/wparcell/Kircher/Mundus/Index.php.

Krever, Mick. “Netanyahu gifted Trump a golden pager during their meeting in Washington.” CNN. February 6, 2025, figure 1. https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/06/middleeast/netanyahu-trump-golden-pager-intl

McMahon, Darrin M. Divine Fury: A History of Genius. New York: Basic Books 2013.

Mishra, Pankaj.“Václav Havel’s Lessons on How to Create a ‘Parallel Polis.’” The New Yorker. February 8, 2017.

Milosz, Czeslaw. The Captive Mind. Translated by Jane Zielonko. New York: Penguin Random House, 1990.

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the American Literary Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Navalny, Alexei. Patriot: A Memoir. Translated by Arch Tait with Stephen Dalziel. New York: Knopf, 2024.

Nover, Scott. “Why Donald Trump Keeps Falling Asleep in Court.” Slate. April 29, 2024. https://slate.com/technology/2024/04/donald-trump-sleep-courtroom-apnea-science.html.

O’Toole, Fintan. “The Second Coming: Disinhibition will be the order of the day in Donald Trump’s America.” New York Review of Books LXXI, no. 19 (December 5, 2024): 1, 6, 8.

Quiller-Couch, Sir Arthur (“Q”). A Lecture on Lectures Introductory Volume. London: The Hogarth Press, 1927.

Rycroft, Charles. The Innocence of Dreams. London: Hogarth Press, 1979.

Shakespeare, William, et al. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series Complete Works. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2021.

Simard, Suzanne. Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. New York: Knopf: 2021.

Sliwinski, Sharon. Dreaming in Dark Times: Six Exercises in Political Thought. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Stonebridge, Lyndsey. We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience.New York: Hogarth Press, 2024.

Ullman, Leslie. “A Dark Star Passes Through It.” Numéro Cinq II, no. 9 (September 2011). https://numerocinqmagazine.com/2011/09/19/a-dark-star-passes-through-it-an-essay-by-leslie-ullman/.

Yeung, Felix S.H. “Psychoanalyzing Democracies: Antagonisms, Paranoia, and the Productivity of Depression.” Constellations (September 25, 2022): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12648.