Interview by Josh Galarza

Blackbird’s inaugural featured artist is Cesar Piedra, a Mexican-American ceramicist and sculptor from Reno, NV, whose practice highlights the myriad ways cultural evolution shapes identity. I first encountered Piedra’s work at the University of Nevada, Reno, where we were cohort-mates in the School of the Arts’ rigorous Bachelor of Fine Arts program. Struck by the depth of Piedra’s research practice and the mindful way he spoke about his work, I was grateful to grow as an artist in his proximity. His work routinely taught me things I didn’t know I needed to know about myself. If the breadth of Piedra’s community engagement is any indication, my experience in his orbit was not unique. It was a privilege to interview Piedra over email for this feature, and I couldn’t be prouder to share his vibrant, challenging work with you. I’ve never met a Reno artist who doesn’t know who Cesar Piedra is, and I’m excited that the same can now be said of Blackbird’s readership.

—Josh Galarza, Art Editor

Your work seems concerned with the expression of intersectional or diasporic identity, particularly identity rooted in your cultural lineage. How does identity interact with history in your art?

When you learn ceramics in the US, you learn Asian ceramics, or rather a bastardized, Americanized version of it, which borrows/loots Asian forms, motifs, and techniques. This knowledge is passed down by a goofy, well-meaning (white) high school teacher. Then, you’re thrust into the world of higher education with an appreciation for Asian pots and sculpture.

So there I was, a Mexican kid making Japanese-inspired tea sets, conforming to the decades-old tradition of American ceramics. I got to sit and dwell on the work I was making and realized how inauthentic my practice was and, in turn, how inauthentic I was. I knew more about Japanese history and ceramics than I did about the culture and people I descend from. After much time researching my roots and the world post-conquest, I began to resolve this identity crisis by blending postclassic Mesoamerican subject matter with that of my contemporary life to illustrate where I “come” from and how that gets altered through time and the intermingling of cultures.

I am not Mexica, Mexican, or Mexican-American—rather, a bastardized version of the three that I like to think of as the hyphen between Mexican-American. My works reflect this journey of the acceptance and rejection of the need to be “authentic.”

The culture of the Mexica features more heavily in your work than that of other civilizations native to what is now Mexico. Were you drawn to the Mexica because of their sheer power and visibility in the pre-Columbian Americas? Or are you descended from one of the indigenous peoples that the Mexica comprised? I’m intrigued because many mestizo people, particularly those in the diaspora, know very little about our indigenous ancestry. Much of my own work relating to mestizo identity is driven by an effort to understand my full self and my full history, so I’m curious if your motives are similar or if they stem from a different set of curiosities.

I too am part of the diaspora that does not know the origin of their lineage, just the immediate folks that are still alive. The origins of both sides of my family are hard to pin down as my parents and their family moved a lot when they were kids due to my grandparents’ migration for work and roles in the Mexican military. Much of their identities comes from where they were brought up, Durango, MX. I didn’t really have a location to base my identity on. We lived in Southern California for the first nine years of my life, then moved to Reno, NV, where I had no real connections to anything that could inform my identity.

I focus on the Mexica-Aztec culture because of my time as a fútbol aficionado. Nothing made me feel or look more Mexican than sporting la Verde (Mexico’s 2010 World Cup jersey). You hear “somos guerreros” (we are warriors) and “los Aztecas” (the Aztecs) in dialogue before and after matches. I found this interesting and wanted to make work that challenged those nationalistic perspectives. I started at the Aztec creation myth, and from there I became obsessed and dug deeper and deeper, arriving at contemporary readings like Mexico Profundo and The New World Border. From there, I began to pose questions about the cultural and social issues that plague the contemporary Mexicano through the lens of art and cultural history.

Much of your work illustrates and even emulates cultural consumption. How does the audience’s experience of consuming a culture, or sharing in a culture that may not be their own, inform your process and your planning of performance events involving audience interaction?

When I was just scratching the surface of making works inspired by Mesoamerican objects, I was doing just that, recreating interesting objects and imagery from the books I was skimming to gain a vocabulary and appreciation for the culture. I would then exhibit the works and feel like the content wasn’t engaging, and that the objects were so far removed from their intended purposes/original context that there wasn’t any entry point for the viewer.

My response to this issue was to be more playful and invite the viewer to engage by activating the work and space. I became especially interested in cultural consumption after reading about objects and the museums they’re exhibited in, so I thought about having my objects looted by the audience. I didn’t want to be in cahoots with anyone, so I arrived at the piñata delivery system. With my ¡¡¡DALE!!! ¡¡¡DALE!!! ¡¡¡DALE!!! piece, I created anticipation by tethering a fourteen-foot axolotl piñata to the wall, anchoring it to a spot where I hung piñata-ized macuahuitl (Mexican warclubs). After breaking the piñata, I didn’t need to instruct the audience to take the culture candy littering the floor; they knew what to do based on their experience with Mexican culture.

When I sold my ceramic objects in El Vendedor, I took inspiration from the street vendors in my hometown in Southern California. I screamed, “Se vende cultura, dulce cultura” (culture for sale, sweet culture), inviting strangers to buy the culture I was peddling as they would concessions at a ball game or event. I want to encourage the idea of intermingling between cultures. I believe that culture shouldn’t be policed and kept from people based on their ethnic background; it’s meant to be shared and experienced so that others can learn, appreciate, and become inspired.

You’re deeply involved in your local art community, and regularly curate group exhibitions showcasing the work of others. Can you speak about your service work, why you value it, and how the concept of community is expressed in your art?

I don’t really think of it as service; I went to school for all of these years to learn how to be a practicing artist, and it would be a major disservice to all that work if I didn’t apply what I learned and continue to build, push, and challenge all of those dialogues.

My curatorial process has always been collaborative and is inspired by the conversations I have with my peers. The exhibitions I put on with my friends are an invitation to propel the dialogue and give everyone involved space to share and time to speak. My practice in the studio is very much in the same vein, as my use of mixed media gives each of the materials a role within the work.

Speaking of, though your background is in ceramics, your work seems increasingly mixed-media. Your recent exploration of fiber arts is particularly intriguing. What informed your decision to go down a new path with felting?

Accessibility. Felting does not require a dedicated studio space but rather a flat surface, some needles, wool, and foam pads. I started felting in my bedroom the summer after undergrad. During this time, the Nevada skies were full of smoke from the California wildfires. Going outside was not an option, thus I dedicated sixteen hours of my days off to turning loose strands of wool into tight forms.

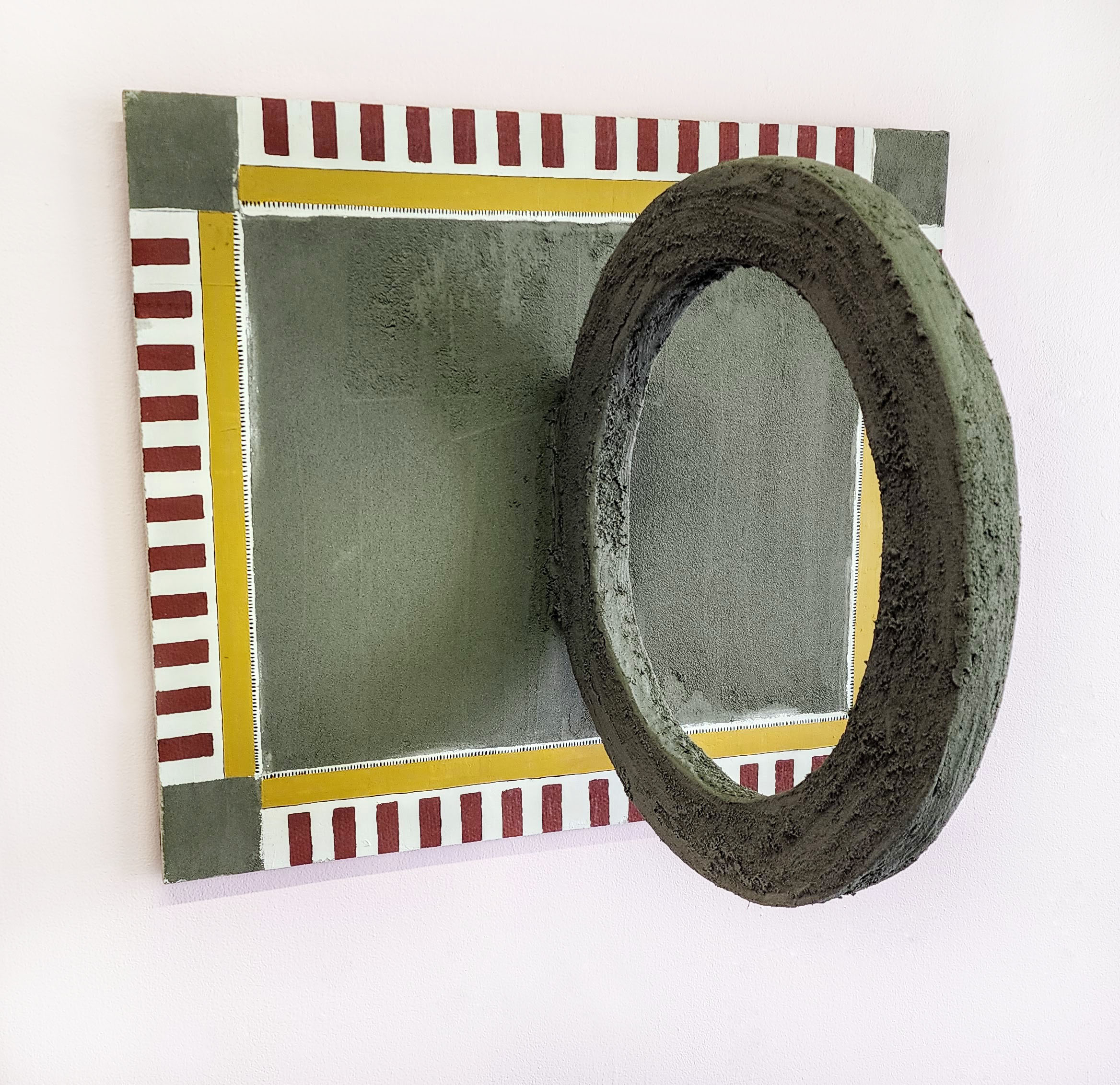

I also needed a break from ceramics and the rough building materials I was using to create works of art. Concrete, plaster, mortar, spray paint, and clay are all so rough on the body. You definitely have to gear up to work with those materials in closed spaces. Not to say that felting isn’t dangerous—those needles can do some damage—but using fiber as a material challenged the expectation of my status as a Hispanic man as the materials aren’t very macho. This allowed me to flip the perceived notions of my establishment art practice on itself. Fiber softened up my works and allowed for an intriguing visual dialogue of the hard and soft within the works.

As a viewer, I can’t help but assume connections between your art-making materials and the cultures your work celebrates. How does the subject matter of your creative research inform the media choices you make in the studio?

Within my research I get hung up on or obsessed with an object/iconography/ritual, especially when there is a contemporary counterpart to compare it to; this dialogue of ancient and contemporary creates tension. For example, The Beautiful Game blends the contemporary sport of fútbol with the Mesoamerican ballgame. The presentation makes reference to the Mexica tzompantli (skull rack), a structure that displayed the skulls of war captives and those ceremoniously sacrificed by the Mexica. The display of human skulls was one way the Mexica legitimized their prowess over their tributary states. I relate this to my exposure to the culture of fútbol, as the sport and its games are weaponized by aficionados, eliciting nationalistic pride and conflict. My use of materials in this piece references the materials of the Mexica culture and their contemporary counterparts. I weaponized the pelota (ball) with obsidian in the same way Mexica warriors would their Macuahuitl (warclubs). This weapon was made to severely injure the opposing individuals on the battlefield, who would then be captured and sacrificed to the god of war, Huitzilopochtli. The use of red earthenware is attributed to the terracotta used by the Mesoamerican culture to make ceramic vessels and sculptures. The concrete pedestal serves as the altar where all of these concepts come together. The presentation is inspired by the tension created before a World Cup match, where the ball sits on a pedestal and the players from both teams stand in the locker room tunnel waiting to “battle” for ninety minutes on the pitch.

Much of your work is displayed in unexpected spaces. I’m very compelled, for instance, by the image of Caninos Canijos hung on a chain-link fence. Can you tell our readers about your impetus to bring your work—even work that is not performance-based—out of the gallery setting and into a community setting?

Caninos was part of a group exhibition by The Holland Project and Window Mine for the Other Places Art Fair OPAF in San Pedro, CA in 2021. For this piece, I requested the work be hung on a chain-link fence. The work depicts a coyote and a xoloitzcuintli. These canids hold cultural significance for the ancient and contemporary people of Mexico. The xoloitzcuintli guides our souls to the land of the dead while the coyote, in contemporary times, guides and traffics the living through imaginary lines into the US. When I delivered the piece, it was pristine white; when I received it, it was a lovely tint of brown, as it was exposed to the beachy winds of San Pedro. The calendar iconography in the work was a mix of Mixtec and personal iconography from my time growing up in Southern California. The intent of these design elements was site-specific.

I thoroughly enjoy messing with established gallery practices and exhibition guidelines. Exhibiting in an alternative art space has always felt like a place where experimentation and play are encouraged. I prefer DIY spaces because they let the Art happen.