Interview by Megan McDermott and Gwen Hall

During a stressful stretch of months in 2024, I began carving out time in my mornings to write and be with art. These little spaces of solace helped sustain me in an otherwise anxious period. Many writing sessions were accompanied by a used book found at the Montague Bookmill (a ridiculously charming bookstore overlooking a river, with the slogan “Books you don’t need in a place you can’t find”), New American Paintings #146. This book was my first introduction to Gretchen Scherer’s work, specifically her painting “A Day at the Met.” While the poem I wrote inspired by this painting remains in the drafts folder, some of the words I attributed to Scherer’s art – “the feeling of being tugged up and open”–continue to feel true as I get to better know her work.

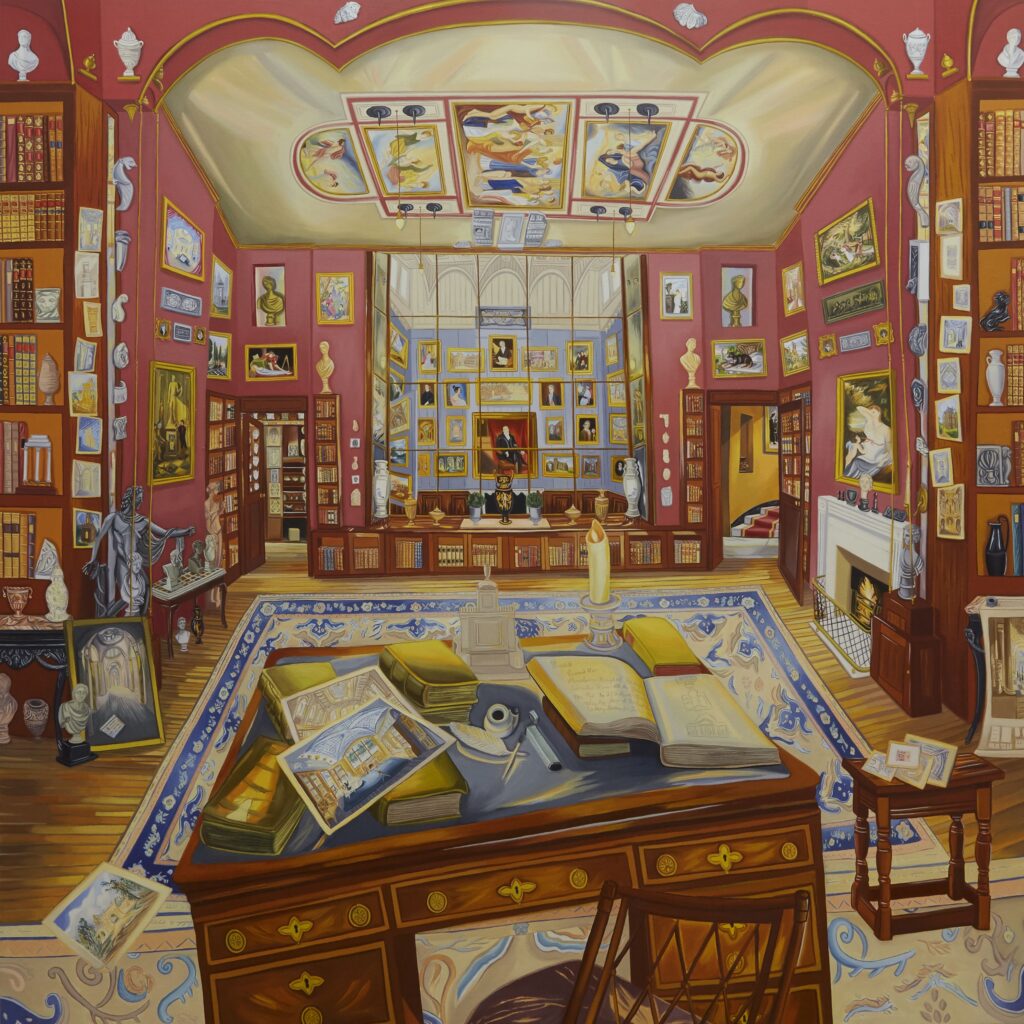

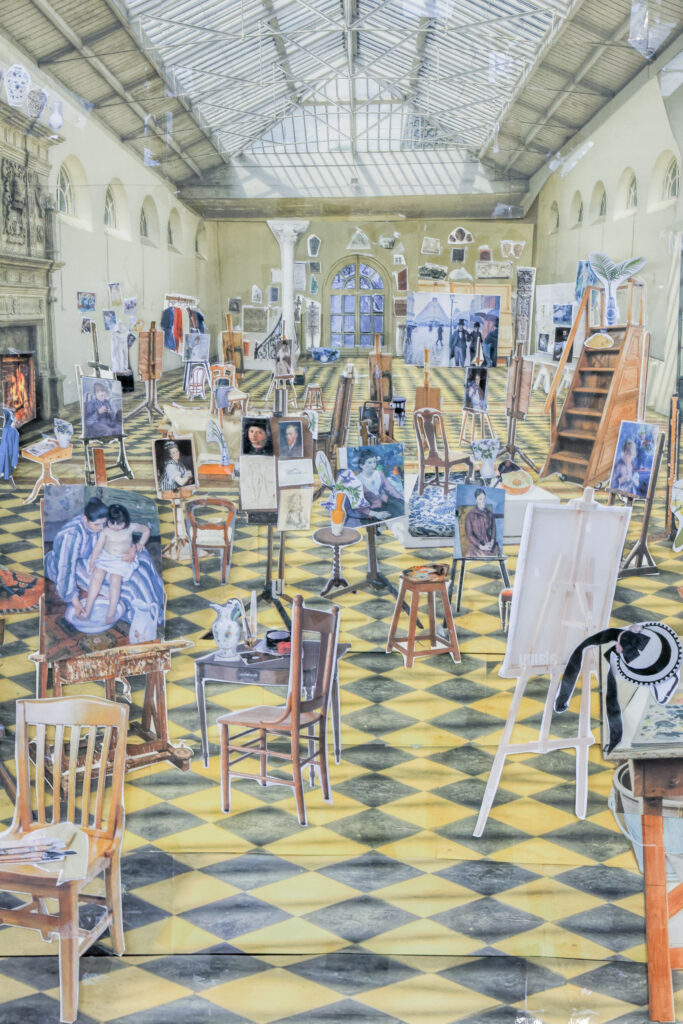

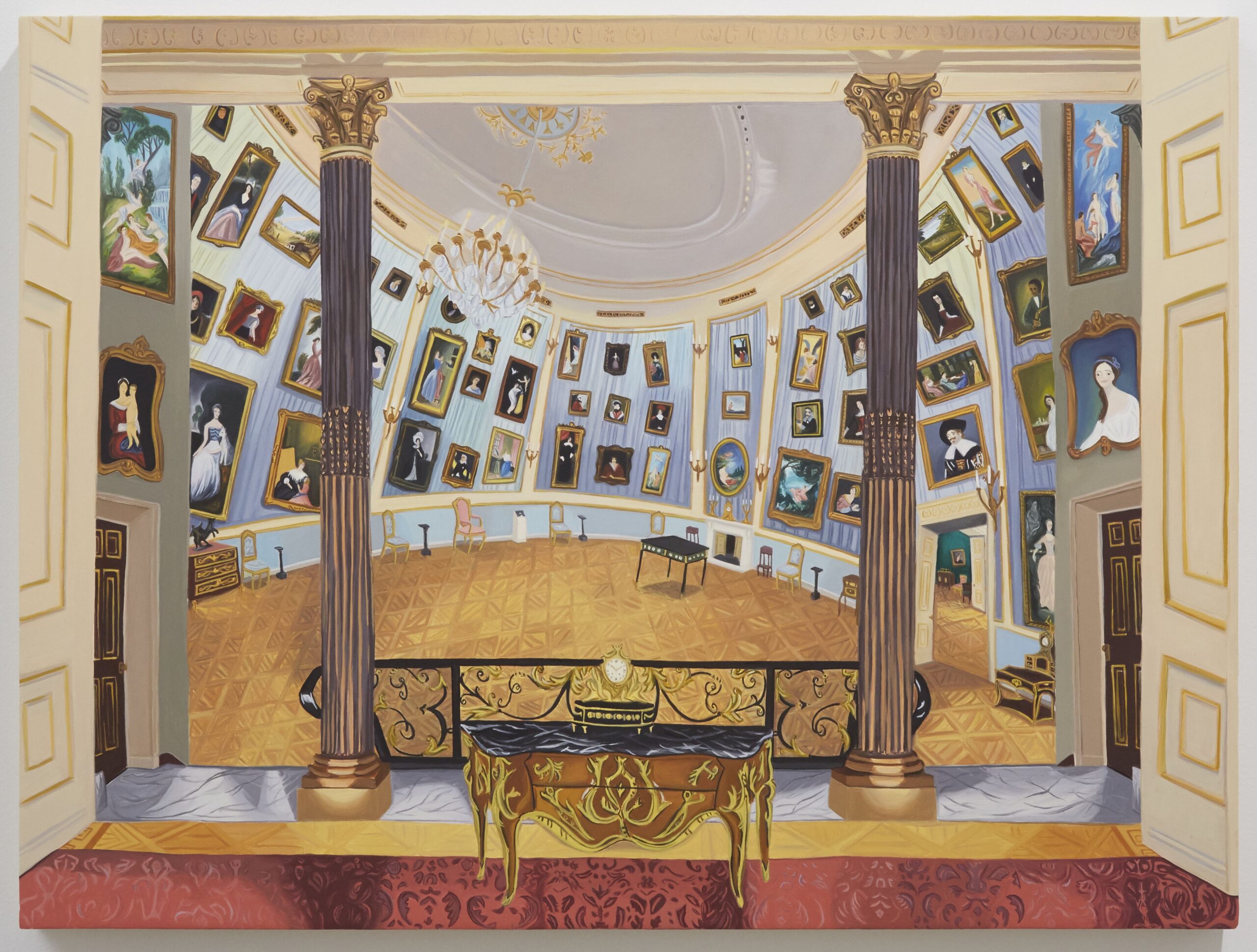

Many of us have been lucky enough to experience the feeling of being tugged open by varied adventures into art spaces. Scherer’s paintings are a testament to that sensation, especially as produced by a holistic experience of viewing a collection or strolling through a museum. In such a setting, our eyes don’t typically feast on one piece alone, but instead take in an abundance of artworks. Scherer evokes that abundance–both by featuring many individual paintings within her own and by highlighting other significant aesthetic details of the spaces she portrays.

This conversation with Gretchen led me to reflect fondly on different art spaces that live on in my own imagination, imbued with memories and emotions across eras of my life: the Yale Art Gallery I frequented while living in New Haven in my early-to-mid twenties; the Prado where I encountered the gripping works of Hieronymus Bosch in the midst of a transition between two distinct periods of my life; and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, which I now walk to regularly from my Richmond apartment, to name just a few. Of course, I have photographs of some of these spaces, and of the work within them that captivates me most–but none of those photographs do justice to the feeling of viewing art like Scherer’s painting do. I am thrilled to begin my time as Art Editor at Blackbird with this conversation between Gretchen, myself, and associate art editor Gwen Hall. From wherever you are reading, may Scherer’s thoughts and works bring you in touch, once more, with the power of viewing art, just as they did for us!

—Megan McDermott, Lead Art Editor

While these paintings show a clear devotion to the preservation of art history, they also do more than mirror important art-historical spaces; instead, they seem to be portals to something alive–pulsing with more energy than some might associate with museums or tourist attractions!

We are curious about the relationship, then, between the paintings and the actual locations that inspire them. How do you choose locations? What would be a dream location to transform into a painting in the future? Conversely, a nightmare location that would pose a particular challenge to your practice?

Thank you so much, I’m so glad they are having that effect on you as a viewer. How I choose a location is hard to describe. It’s almost like the space says yes to me and I say yes to it. Sometimes, I’ll really want to paint something but I get the feeling I shouldn’t. Sometimes it takes time for me to commit to it or believe I can do it. I print out pictures of a place and just look at it for months before I fully decide.

In terms of what I do to choose the actual location, I believe emotions impact how we see and experience a place. When I am composing a painting, I try to imagine it anew, more based on how it makes me feel versus what it actually looks like. So, it has the elements of that space, but they are altered–heightened or enhanced in some way. Every painting begins with a collage that serves as a study for the painting. The collage is usually made up of pieces of the actual room but sometimes I’ll incorporate details from another part of the same house or sometimes a different location altogether.

A dream location for me is something I came across recently actually, a place called Gregynog Hall in Wales. It’s the former home of two sisters, Gwendoline and Margaret Davies; they began collecting impressionist paintings in the early 1900s, and I’ve never come across a house and collection owned solely by women. I’m really excited to try and recreate what their home might have looked like with their collection. A nightmare might be a very spare, minimalist interior with just a couple of items in it. It would be very difficult for me to paint something with so little detail.

We would love to hear more about your process of making these places seem so evocative and real. These spaces often powerfully display wealth, but in your work, they never come across like stale fantasies of grandeur. Are there limits to the process of imaginatively engaging these locations? As you’ve continued to explore this subject matter over time, how do you push past those limits through experimentation and adventure?

I think to me they aren’t about wealth; I can’t help but bring my own experience to these places. I spend a lot of time working on the collage that I use as a study for the painting. I try to make it feel like a real miniature room that I can get lost in and feel like I’m sort of “living” in it for the duration of the painting process. Maybe that transfers over to the viewer. I hope so!

I have a way of working that is pretty rigid, and I go through the same steps each time and at each stage in the creative process. Within those constraints there can be a feeling of routine and familiarity. Each painting is a challenge, and I’m not sure if I’m going to be able to make it work. I slowly introduce new things. It’s very exciting when I come across a new way of arranging a composition.

Experiencing things in real life that are totally different from painting and then trying to put them into a painting form helps me find new ways of thinking. It could be something I see while on a walk in nature or watching something like dance. Anything that is very beautiful can start to open up my thinking on how I could arrange a composition in a different way.

Continuing to think about the impact your imagination has on these spaces–we sometimes saw more warmth and whimsy in your versions of these locations than in photographs we found of them. Particularly, the lived-in quality you give many spaces, and the use of curvature and tilted space, makes grand, ornate settings feel more accessible than they might feel otherwise.

We wonder if invitation or welcome is something that you think about, either in your creative work directly or your overall life as an artist, especially since many viewers of your paintings may never get to see these places in-person. How, if at all, are hospitality and accessibility factors or values in your art?

Yes, definitely. Invitation or welcome is really important to me. I do hope people who haven’t seen these spaces can feel transported and somehow experience these places in painting form. I also haven’t been to a lot of the places I paint. In my paintings, I kind of want the flaws to be there even though it can be uncomfortable for me. I might want a certain area to be different, or I might want to “fix” it, but in the end, as long as it works within the painting, it’s okay with me. I hope this makes the spaces feel more lived in and allows the viewer to enter into the works. I find when a surface of a painting is really “perfect,” it can repel or push the viewer back out, in my experience of looking at art. I’m trying to make something that people feel like they can freely enter and “roam” around the space.

Relatedly, your works may technically qualify as still life portraiture, but they are certainly anything but still. Previous reviews have referenced your work as “prophetic” regarding the haunting reality of lockdown in 2020. When making choices such as a folded napkin, a pulled out chair, or a painting slightly askew, do you imagine characters (past or present) inhabiting the space? As writers, we would love to hear more about this, particularly since the lack of people in your paintings could either signify absence or us, as viewers, being the primary human presence.

Yes, I remember 2020 very well. That was a little creepy when I happened to have a show open with paintings of empty museums right when lockdown started. It is true that the spaces are empty, but I also want the spaces to have a human presence and not feel empty. I do imagine people from the past being there, and I really want the viewer to be able to imagine themselves inhabiting the space. I find when you put a figure in a painting of an interior, often that figure becomes the focus. Through the art I include and the placement of the objects, I try to make it feel inhabited. Because my paintings are about spaces, I want the space to remain the primary thing that grabs one’s attention yet at the same time you might feel there’s someone there.

These paintings often include hallways and stairwells. In addition to transporting us to homes, estates, museums, etc., all over the world, there’s a sense of transportation and movement happening within these spaces. Meanwhile, doors and curtains often seem to suggest that there is more to explore. How, if at all, do you think about the possibility of evoking movement when you’re working?

I think of movement within the spaces often. I try to make sure there is “a way out”–somewhere else the viewer can go, that they’re in this room now but there’s something else right around the corner. I also think about the objects in the room being a little bit askew or as if they were just set down for a moment. Sometimes I’ll place a similar object type around the room–for example, a bunch of drawings on paper sort of scattered about–as a way of adding movement.

These works–while clearly including several iconic paintings within them–seem more interested in capturing the overall impression or experience of art (as one gets when strolling through a gallery) than celebrating the individual, great artist or the power of one great painting. Even in The Wallace After The Swing, Fragonard’s The Swing is literally off-to-the-side, de-centered. Do you find this reflects any of your own thoughts on the role of the artist in relation to art itself? How do you relate–or not–to the idea of a “masterpiece” or “the canon”?

That is a really interesting observation. In The Wallace After The Swing, I placed Fragonard’s The Swing in relation to the chandelier that is also painted as if it’s swinging in an upward motion. The whole room is a little bit off-kilter to mimic the feeling of swinging. I think you’re right, though, that I don’t make the masterpieces stand out. I think the relationship of the artist to art itself is that we don’t really know what we’re making at the time of creation or how it will be thought of over time. So I think a masterpiece is decided by the viewers through the years. I’m painting these spaces a little more from that point of view.

We are blown away by the scale at which you work–18×24 is not large at all for pieces like the Sanssouci Palace, Palace of Aranjuez, and Belton House Staircase! Your attention to detail remains undaunted. How do you arrive at the sizes you work–industry standard, availability, or some other third thing?

It might be a combination of a couple things. I feel the representation of art works best for me in miniature, and I think juxtaposition in a painting can make it stronger. If you take a very grand room and shrink it down, you automatically have this extreme juxtaposition. I like the idea that the viewer can stand in front of it and see the whole thing and not have to move around too much. They can take in everything at once. It is a more intimate experience.

Another factor is time. I really like to add a lot of detail, and the bigger the size, the longer it takes to make all those details across a larger surface. I do enjoy working larger at times, but it is a challenge. I tend to still keep the scale of the paintings and the furniture miniaturized. Small is where I feel most comfortable.

In the LA Review of Books, writer Matthew Jeffrey Abrams reflects on the Trubetskoy Palace and its relationship to modernist art, saying, “Most rooms in Shchukin’s palace, like the dining hall, were explosions of molding, gold, mirrors, and ornament. But this is something most people, even curators, tend to forget…modernism itself, like its environs, was not hard edged, sterile, or spare.” This kind of setting stands in contrast to many contemporary museum or gallery settings. How do these historic spaces you feature challenge contemporary conceptions about the ideal settings or conditions for viewing art?

Oh wow, I love what Abrams wrote! One of my paintings in my solo exhibition, Seeking an Exit at Monya Rowe Gallery, was of the Trubetskoy Palace. I thought about this very thing quite a lot because the existing photos of the palace are in black and white, and I was trying to imagine what they looked like and what colors everything should be. I had the collection, but very little idea of what the decorations were truly like. There are these wonderful written descriptions of the rooms in the book The Collector: The Story of Sergei Shchukin and His Lost Masterpieces by Natalya Semenova and André-Marc Delocque-Fourcaud, so I did take some cues from there. Modern art is very colorful, and each piece is very different stylistically, so the challenge was: how do I make everything somehow go together? Surprisingly, I was able to first arrange the paintings on the wall and then find colors for the walls, ceiling, and drapery that worked with the paintings. This is a long way of saying, I don’t think the rooms need to be so sterile and white. Even though modern art is very eclectic, I think there’s room to change, and it might be really exciting if we let ourselves try some new things. There is a natural conversation, no matter how subtle, between the art and the architecture, so how can we continue that conversation or make it more of a back and forth? I think as art evolves, architecture also evolves, and the more they talk to each other, the more interesting it can be.