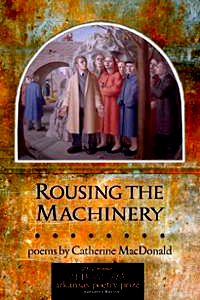

Review | Rousing the Machinery, by Catherine MacDonald

The University of Arkansas Press, 2012

|

Both intensely personal and disarmingly distant, Catherine MacDonald’s debut collection of poetry showcases the poet in the midst of a crucial investigation. In the process, she stumbles and ad-libs, idealizes and compromises. Consider the opening poem, “Grace”:

This is my footpath to Grace,

seventh house on the left. An air conditioner,the only one for blocks, sweats and sighs

in her jammed-open front window as Augustsimmers.

“I knock anyway, every day,” MacDonald writes. “Drawn by the monkey’s cry and the air conditioner’s / cold invitation, I face Grace on her front stoop.” The double meaning of grace is irresistible. The young speaker’s unassuming conflation of her neighbor’s given name with unmerited divine love manifests the underlying impetus of Rousing the Machinery: lacking a clear path to understanding, the poet will forge one despite impediments and warnings.

To that end, the machinery invoked in the collection’s title takes on multiple significances. It connotes the workings of both the known world and the mystifying universe, the fabrications that humanity imposes upon them, and the machinations of the individual within them. Initially, MacDonald’s machinery operates around and independent of her speaker, and though its gears and lights gleam beautifully, its inherent danger pervades the poetry, as in “Blue Strobe”:

square above a racing river,

the velocity of its current calculated

remotely by strobe and transmitted

via satellite to engineers who wait

restlessly to wring meaning from raw

data. Six boys, hands flat on the hood

of an unmarked police car, circa 2008.

Its blue strobe is the river’s pulse at its sharpest

bend, wildest branch, and highest bluff.

In the following poem, “Notes on Prison,” we see the “big machine” of the corrections system that grinds inmates down, the machine we’re meant to rage against. Danger inhabits this place as well, but an intriguing sense of logic and elegance undercuts it:

Carlos is a man with a business plan,

an artist from Jalisco. He shows us

his sketchbook: the Basilica

of the Virgin of Zapopan, patroness

of epidemics and thunderstorms. His sister

strumming the vihuela. A man’s open palm.

But here, it’s reverse paintings on glass

for sale or barter—maybe Disney

for baby or one of the Bible’s bad boys

for mama, or your sweetheart’s

face copied from a wrinkled photo.

As MacDonald’s collection progresses, her speaker approaches machinery like this, with oblique and tentative steps, cultivating a magnetic attraction to it. Poems in the vein of “Indian-Style, In Front of the Tube,” “‘House-Hunters,’” and “How to Leave Home” acknowledge the inevitably growing divisions between people—brothers and sisters, children and parents (“We outnumbered them, but they outweighed us, / bringing to the table clear advantages”)—driving at the need for external reason and structure.

As we move into the collection’s second section, its emotional core shifts to the internal. The speaker—as pregnant woman, as mother—envelops the workings of the world:

Watch: the miracle

occurs in a vessel, an enclosure, in a lidded pot

on a hot stove, in a woman’s body

where a child grows, or in the insect

jaw, ganglia, and lobe.

As the engine that produces life, the female body houses some of the most remarkable machinery on the planet. Through MacDonald’s treatment, by turns reverent and fatigued, bearing a child takes on a utilitarian edge. The child, consequently, becomes product as well as progeny, and a son’s maturation evokes pride and alienation in equal parts.

MacDonald illustrates this phenomenon wondrously in a number of poems, notably “Appetite” in which the speaker marvels that, “After a semester away, my son is observing / Ramadan, fasting from sunrise to sunset.” The pair wanders the grocery store together, mother tempting son with what she can provide him, attempting to bridge the increasing gap between them with produce. Ultimately, though, she asks, “Is it enough? I cannot see yet // how his uneating will lead him from hunger / to hunger.”

Delving further and further down this rabbit hole eventually yields disorienting and devastatingly practical results. “Some Mothers Ask,” with its regular couplets and purposeful rhythm, carries the reader along in an irresistible current. In the second section the speaker reveals that she has miscarried and, in the aftermath, donates the milk that her body produces to “a crack-baby served by prescriptions, / the infant of a mother with implants or AIDs, an infant // fostered.” Her sorrow is palpable, playing off of the selflessness of her breast’s gift and reflected in the poem’s imagery:

After each miscarriage, it’s new mothers who move me

most. I find them in grocery store lines wheeling a carthalf-full, mewling infant sunk in a sling, in restaurants,

shy, nursing through a hurried meal. I know mother-hunger and baby-lust are yoked to the body-ox—

but what match fires that slow fuse? Every night I dreamof catastrophe, and each day carry out one useful chore.

No more sticky kitchen shelves. No oily imprint of the collieon the dining room floor. My shallow drawers hold

armloads of homely objects, each with its deep intentionto pierce or measure out. A tiny fork. Hollow-handled

medicine spoon. Look—six scallop shells—a wedding gift,cradles for sinew and bone. We use them as scoops, as ashtrays.

Repurposing, it’s called.

Body-ox. Shallow drawers. Hollow-handled medicine spoon. Repurposing. The comparisons and actions in “Some Mothers Ask” bear repeating. They estrange; they commodify; they crush the reader in agonizingly precise teeth.

The final section of Rousing the Machinery opens with poems—“Russian Studies,” “RAF Station, Norfolk, England, April 1940,” and “Yokota Airbase, Japan, 1961,” for instance—that transport the reader to foreign locations and cultures. These stand as a reprieve from the inner workings of the human body and a rediscovered interest in simplicity:

Clouds arrive all morning from long ago

he recalls the lacquered discs of an abacus

under his five-year-old fingers clicking.

Names of friends and family members repopulate the text at this point as well. Instead of he and she, an infant or the son we have Emile and Ellen, Newell and Charity. Not since Grace from the collection’s opening poem have specific people emerged and identified themselves so. Humanity, in all its glorious imperfections, takes center stage again, interposing itself between the reader and the oppressive mechanics of the world. Along with this movement, the speaker resurfaces in the final poems “Teaching Myself to Sew,” in which she attempts to follow her father’s example:

my stitching pulled loose from the cloth.

Because I studied his face more closely

than his hands, I never saw how he began,

with that necessary snarl, the knot in the strand.

and “Sing Whatever Is Well Made,” in which the drive to a family reunion stirs memories and implies obligations:

In the grand

tradition of my class, I’ll wash our shorts and shirts and socks,

treat the stains that remain, soften pilled fabric. A tender,

a keeper, I’ll make it right, sweep the seats, wipe

the kids’ prints from rear windows, point the car home.

Ultimately, it is impossible to separate the person from the machine, the father from the stitching, the mother from her children’s prints. MacDonald’s poetry bravely and honestly deals in this fact’s recognition and reconciliation. ![]()

Catherine MacDonald is the author of Rousing the Machinery (University of Arkansas Press, 2012), which won the Miller Williams Arkansas Poetry Prize. She teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University.