How Is History Made?

Marge Betley, Dramaturg

In March 1848, two young girls in a tiny hamlet thirty miles southeast of Rochester claimed that they had discovered the means of communicating with the dead—in this case, with the spirit of a peddler who had been killed in their home some years earlier. The story spread with a swiftness that is staggering—almost as quickly as the recently developed technology of telegraph communication—and the Fox sisters became unwitting celebrities in a rapidly changing American landscape. What was it about this family, about this period in history, about this place on the expanding American frontier that made their story possible? Truly, it was like lightning in a bottle: the perfect convergence of geography, technology, belief and timing.

|

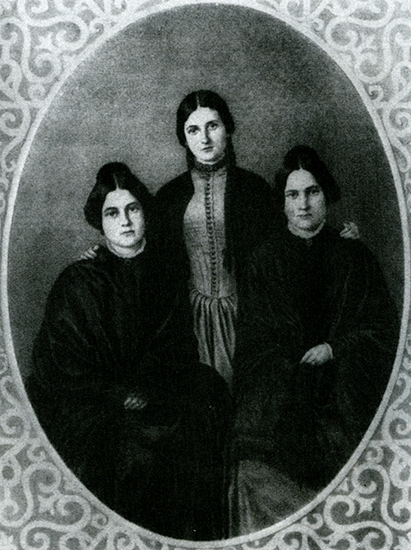

| Perhaps the most famous image of the Fox sisters, this lithograph by N. Currier (of Currier & Ives) depicts Maggie and Kate Fox and their older sister, Leah Fish. Courtesy of the University of Rochester, Rush Rhees Library Department of Rare Books and Special Collections |

Much about the Fox family history is murky and open to debate, with wide-ranging disparities among the many books written on the subject. Even the age of the sisters at the time of the events of March of 1848 remains uncertain. Most sources put Catherine (also called Cathie or Kate) and Margaretta (Maggie) Fox at eleven and fourteen, respectively, but some indicate their ages as nine and eleven. Perhaps the details weren’t recorded meticulously because no one ever expected the two to become such icons. Perhaps it’s because almost immediately, a sense of legendry and hyperbole attended their fame. In still other cases, there have been those who manipulated the facts to exploit the girls for their own gain. Even in the case of this play, writer Dan O’Brien has blended fact and fiction in the service of a theatrical story, one that makes no pretensions to documentary.

There seems to be general agreement, however, that John and Margaret Fox moved several times before eventually settling in Hydesville, in Wayne County, New York, in December 1847. Most recently they had been in Rochester for several years, following a somewhat longer stint in Canada where Margaretta and Catherine were born in the 1830s. It seems that financial difficulties were often the cause of their moves, and when John and Margaret made the transition to Hydesville, it was into a modest, rented cottage (near their son David) that had served as a temporary rental home for other transient families before them.

|

| The house in Hydesville was already known as the “spook house” when the Fox family moved there in December 1847. Courtesy of Plymouth Spiritualist Church |

Canal Towns and The Burned-Over District

Rochester by the 1840s was more refined than the burgeoning canal town it had been in the ‘20s, with a growing upper class and intellectual community and a focus on self-improvement that had grown out of earlier religious revivalism. Wayne County, on the other hand, still carried a frontier spirit. Much of western New York (which had been part of the Iroquois Confederacy) had only been opened to white, European settlers in 1789, barely three generations earlier. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 radically changed the region, opening up commerce and encouraging emigration and exploration. As Wayne County historian Peter Evans noted in his conversation with us during our preparatory research for this play, it is rarely the wealthiest, most established families that pick up their lives and move everything they own during such periods of emigration and expansion. It is typically those who have not been successful elsewhere, or who are eager to exploit the riches that undeveloped territory may offer. Consequently, the rural areas along the Canal attracted entrepreneurs and risk-takers, both the desperate and the savvy.

This new American landscape, rife with death, disease, and hardship, as well as opportunity, demanded its own brand of faith. And so Rochester and its environs in the 1820s became known as the Burned-Over District because of the quantity and fervor of religious movements that swept through the region, figuratively charring the landscape with fire and brimstone. Barbara Weisberg, in her biography of the Fox sisters, Talking to the Dead (HarperOne, 2005), describes it this way: “The region had periodically erupted in evangelical revivals from the early 1800s on. Men and women who headed west, abandoning the settled communities of their youth, craved a faith that matched their fervor and offered solace against the hardships and diseases they faced.” They rejected European concepts of a divinity that they viewed as essentially passive. They wanted a spiritual life that was as active in pursuit of salvation as they were in pursuit of their own earthly survival. The spiritual movements that were born out of this were quintessentially American, including the Oneida utopian community, the Mormons (whose founder, Joseph Smith, claimed to have received his initial revelation from the angel Moroni just ten miles from Hydesville, in Palmyra), and the Quakers, whose emphasis on a personal connection to God found its logical extension in active social reform issues, such as women’s suffrage and the abolitionist movement.

The Rochester Rappings

Just a generation later, this was the geographic and spiritual landscape into which Catherine and Margaretta Fox were born. Yet when they moved to Hydesville in 1847, their lives actually became considerably more isolated. The hustle-and-bustle of city life was left behind in Rochester and suddenly they found themselves in the vast quiet of a rural community in the midst of a western New York winter that was cold enough to stop the flow of Niagara Falls for thirty hours on March 29 due to an ice jam.

The house they had moved into was known locally as the “spook house” because of the odd sounds that previous inhabitants had heard. Indeed, in the months leading up to March 31, 1848, the Fox family had heard unexplainable sounds on numerous occasions—sounds that were sufficiently disturbing that the mother Margaret Fox later noted that their ability to sleep at all had been seriously compromised.

And so it was on the evening of March 31, that the family had gone to bed early in the hope of finding the rest that had been eluding them. The sounds began shortly after they retired, and increased quickly in volume and intensity. What was different on this evening, however, was a moment that is now legendary in the Modern Spiritualist church. One of the girls called out to the sound: “Mister Splitfoot, do as I do.” She then proceeded to clap her hands three times, and the source of the sound responded in kind by rapping three times. That simple but critical decision to address the source of the sound as though it possessed intelligence and comprehension had ripple effects that persist to this day.

Within less than a month, a pamphlet was published containing the affidavits of numerous witnesses to the rappings, including Margaret and John Fox, their son David, and assorted neighbors. What is remarkable in their testimonies is that each seems genuine in his or her wish to find some non-supernatural explanation. They do not offer hypotheses about how the sounds are made; rather they offer only their own wonder at the mysterious noises.

Once the sisters established “contact” with the spirit in their home (reportedly, a peddler who had been murdered in the house years before), their ability to communicate with spirits expanded beyond him, and beyond the confines of the house in Hydesville. Eventually, the spirits seemed to follow Catherine and Margaret wherever they went, and they developed their talent at contacting specific spirits, including the dearly departed relatives of a wide range of admirers and supporters.

The Spiritual Telegraph

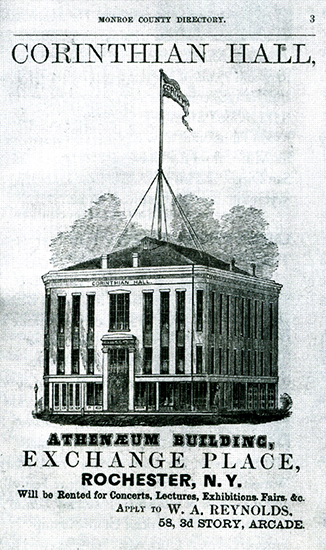

It is almost hard to conceive just how quickly news of the Fox sisters (and what became known as “the Rochester rappings”) spread. In November 1849, less than eight months after the original event, Kate and Maggie gave a demonstration of their abilities at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall for an audience of more than four hundred people. Several weeks later, a report of the proceedings was published in the New York Tribune by Horace Greeley, who would go on to become one of their most ardent supporters. By 1850, the girls launched their first professional tour, eventually traveling widely in the US and abroad, and in 1853—just five years after that cold March night—a petition with fifteen thousand signatures was sent to Congress, asking for a federal investigation of Spiritualist claims.

For those who believed, Spiritualism offered evidence of the continuity of life—of life after death. Communication with those who had “passed over” was likened to the invention of Samuel Morse and was even christened “the spiritual telegraph.” As the century progressed and so many young men were lost to the Civil War, killed far from home and often with little information to send back to relatives, the desire to communicate and find closure beyond the grave had an extraordinary pull.

|

| The Fox sisters’ first official public demonstration of their abilities took place on November 14, 1849, at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall. Over four hundred people attended, paying an admission fee of 25 cents per person. (50 cents admitted one gentleman and two ladies.) Courtesy of the University of Rochester, Rush Rhees Library Department of Rare Books and Special Collections |

Throughout the nineteenth century, some of the most respected and influential thinkers and reformers in America and Europe, from Frederick Douglass and Horace Greeley to Amy and Isaac Post and William James would take an interest in Spiritualism, and some (like Sherlock Holmes writer Arthur Conan Doyle) would become true believers and staunch defenders of the faith.

The National Spiritualist Association of Churches was founded in 1893. The Spiritualist assembly at Lily Dale (in Chautauqua County, New York) is still active, as is Plymouth Spiritualist Church in downtown Rochester, and some four hundred others around the country.

In hindsight, it is almost unimaginable how, from a single, humble moment in time such a cascade of history and faith could flow. But consider “the butterfly effect” in the science of chaos theory. The theory tells us that the effect of the beating of a butterfly’s wings, by the time it reaches halfway around the world, can cause a tsunami. Seemingly inconsequential events, stretched over time and space, can have ripple effects that stagger the imagination. Surely, young Catherine and Margaretta could have no notion of where that one simple invitation—“Mister Splitfoot, do as I do”—would lead. ![]()

Marge Betley is a freelance dramaturg and the Executive Director of Stagebridge Senior Theatre in Oakland, California. She has worked with The Sundance Institute Theatre Lab, Arena Stage, the Colorado New Play Summit, and many others including Geva Theatre Center where she led the New Play Development Programs for over a decade. The House in Hydesville was one of more than a dozen world premieres produced by Geva during her tenure there.