Introduction

Native Chicagoan, but long-time New Yorker, Julian Street is described in his 1947 obituary, as a “novelist and essayist,” an “intimate friend of Booth Tarkington,” and the recipient, from the French government, of the Chevalier's Cross of the Legion of Honor "for his work in popularizing knowledge of French wine and cooking.”

The phrase for which he may most be remembered, however, references Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase #2, on display at the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, commonly referred to as the Armory Show. In the essay, “Why I Became a Cubist,” published that same year, Street says of Duchamp’s painting, “It seems to me to look like the explosion of a shingle factory.”

“Why I Became a Cubist” appears in a 1913 issue of Everybody’s Magazine, an American magazine that published from 1899 to 1929. The issue containing Street's essay is true to the magazine’s name, with an appeal to a wide audience and including in its pages fiction, political commentary, jokes, and generous illustrations. Street's comic essay is sandwiched between two pieces of fiction—a romance, Bonnie R. Ginger’s “Blue Roses” and a western, “The Iron Trail,” by Rex Beach. The essay appears just a year before publication of Street’s Abroad at Home, a nonfiction book detailing visits to twenty American cities and illustrated by Street’s collaborator, Wallace Morgan.

|

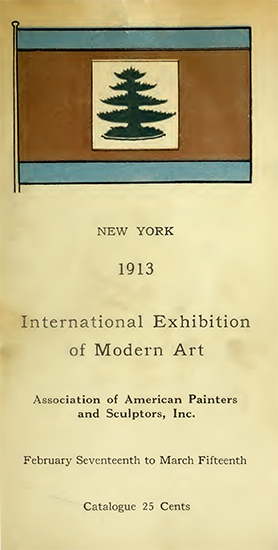

| Catalogue cover for the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, commonly known as the “Armory Show.” |

“Why I Became a Cubist” is a treatment that provides insight into the Cubist movement while simultaneously poking hard fun at it. Street mocks the movement’s enthusiastic backers, art types, and academics, who long for everyone to have—note Street’s ribbing use of capitalization here—Understanding of the movement. The catalog for the show, which is available in the suite for download, confirms the article’s citation of the Duchamp title, as hung in the 1913 show, as Nude Descending a Stairway. It also confirms the use of Paul—rather than Pablo—Picasso in the essay’s label for The Woman with a Pot of Mustard.

In “Why I Became a Cubist,” Picabia’s Dance at the Spring is published upside down (an occurance that probably took us too long ourselves to realize when resetting the piece). We have noted this misorientation in our presentation of the essay here and give readers the chance to see the image rightly oriented with a mouseover. The internal speculation at Blackbird was whether or not this was a deliberate act in the 1913 layout, given the reference in the essay of an Armory Show painting (though not Dance) being hung upside down “through a quite natural mistake.”

We'll leave the final judgement on Everybody’s Magazine’s editorial intent up to readers, but we have also discovered, and republish here as a post-script, a commentary by Everybody’s editors after receiving “numerous letters” pointing out the painting's misorientation. Finally, a brief passage from Julian Street’s 1947 New York Times obituary gives insight into his writing process, and touches on his passions as a food writer, noting the genre that closes out his writing career.

|

| International Exhibition of Modern Art Armory Show, February 15–March 15, 1913. |

Street's quote about Duchamp, much circulated, though often truncated and slightly misquoted, is sometimes attributed only allegedly to Street or is attributed to another individual. Street is also, because of the Cubist essay, wrongly cited in passing as an “art critic,” and sometimes further misattributed as a New York Times art critic, but we are not finding evidence of this.

It seems more fitting, in the 1910s, at least, to characterize him as a humorist—if a cultural critic via said humor, a travel writer, and a fiction writer. Perhaps—as one our our editors speculates—it is the fact that he was not an art critic that gave him license to write about the Armory Show as freely, and as bitingly, as he does. Whatever the case, Street's voice and humor, across a hundred years, still sound out true and strong, and will strike familiar chords to any of us who have recognized, in the art, literature, or culture of our own time, the opening—and challenging—moments of paradigmatic change. ![]()