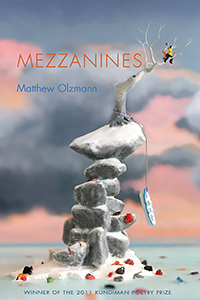

Review | Mezzanines, by Matthew Olzmann

Alice James Books, 2013

|

|

Enter the mouth of the gift horse. “Pry the jaws back / and stare through the phlegm that falls / between the teeth and the hallway of the throat,” writes Matthew Olzmann, “because the world is beautiful, / haunted, and begging you to receive its offering.” Enter the imaginative world of Mezzanines where, as the book’s title suggests, poems inhabit intermediate spaces, navigating the “in-between.” In this prize-winning debut, Olzmann writes narratives from a new angle, making strange connections and quirky comparisons that aim to capture the lyrical moment. Poems shift from storefronts to asteroid fields, from Facebook to Bigfoot, weaving together a cohesive collection and a series of insights that traverse the enduring themes of faith, love, and identity. In this book, we discover a warm and playful speaker whose keen awareness and penchant for metaphor attempt to put a finger on the very nature of existence.

Unlikely juxtapositions and associative leaps provide the core strength in Olzmann’s work. Within many poems, the lens zooms in and pans out, creating jumps in space and scale, where objects and ideas soar or plummet with great velocity. Olzmann’s poems can address a wild premise—a mother who discovers on her baby’ s video monitor a space station hurtling toward earth — zip to a magician whose gloves transform into “two fuming ravens that shriek[ed] around the room,” then zero in on the speaker’s spiritual reflection and contemplation:

. . . I’ve known people, afraid

of the sun, who opened their eyes to God, but found

only a wine cellar lit by a guttering lamp. There’s so much

to be afraid of, so much to gaze at and be wrong about.

Throughout the collection, we discover a speaker both a skeptic and believer, a questioner positioned between the limitations of earthly experience and the possibility of transcendence.

In one of the book’s most direct and humorous expressions of faith and frustration, Olzmann pens eight short missives “For a Recently Discovered Shipwreck at the Bottom of Lake Michigan.” The writer begins his one-sided exchange with questions addressed to the boat (“So what’s it feel like to have everything inside you still / ‘intact’?”). By the third letter, the writer’s thoughts surge toward spiritual concerns, offering a fresh look at the conflict between reason and belief:

April 24th, 2010

Dear Shipwreck,So I was talking to my priest the other day. He’s worried that

I’m having some kind of existential crisis. Meaning: I’m trying

to rationalize God by replacing the ephemeral with a tangible

object. Or: I’ve replaced one object that’s been hidden from

view with another object that’s hidden from view. Or: every

time I speak to you, I’m talking directly to God.If this is the case: Lord, I noticed you haven’t written back yet.

The conversational tone and absurd context of the message disarms the reader, making more poignant the depth of the speaker’s grappling. Tonally, the subsequent letters reveal the speaker’s growing irritation; they move through sarcasm (as in the next note’s greeting: “Dear Shipwreck/Dear Metaphor for God,”) and anger (“Fuck you, boat.”). In a statement of both recognition and resignation, the speaker empathizes with the unreachable ship/God in his final missive: “I know what it’s like to sink, to be angry because no one on / Earth knows if you exist.” The beauty of this series resides in the way Olzmann calls attention to the device of substitution, ironically noting the method of metaphor, while heightening our awareness of his figurative constructions.

The pleasure of Olzmann’s poetry lies in its combination of careful craftsmanship and surprising images. His technical and inventive powers show off in the sonnet “While Scratching My Wife’s Back, I Calculate the Distance Between Sky and Earth.” In the context of performing a tender yet mundane task, the speaker envisions his wife’s otherworldly origins:

In the space where my wife’s wings must have been

there are no scars, no broken screws, hinges,

or binding clips. There is only her skin.

Grounded by the physicality of the body, Olzmann launches the imagination into the celestial realm, creating a space filled with possibility. In subsequent lines, the speaker feels guilty that his wife’s wings “were severed, / erased when she opted to be married / to a man built with more clay than wind.” He suggests we all have a choice “to fall: without memory, meant to land // with what catches us.” The sonnet’s conceit brings to mind Icarus, who attempted to escape Crete by means of wings made from feathers and wax, but who ignored his father’ s warning and flew too close to the sun. The melting wax caused him to fall into the sea and drown. In this case, the wife’s “fall” does not lead to death or failure. Instead, the final couplet illuminates the power of free will and her preference for a gritty, flawed, mortal existence with her husband in “a new, coarse Eden,” challenging the ideal of a perfected, purified paradise.

In Olzmann’ s hands, irony and wit unhinge ordinary events, opening them to larger issues. The poem “Spock as a Metaphor for the Construction of Race During My Childhood” confronts what it means to be biracial, to be forced to consider alternate or imposed ideas of the self. We learn that the speaker has a “German father” and a “Filipino mother” and that he thought he was “like all the other kids / until [his] best friend said, No, you’re not.” His paradigm shifts; the revelation “mess[es] with things like gravity and light,” making him feel:

half-alien, staring down an eternity

that was both limitless and dangerous

as a captain’s voice boomed from above:

Brace for impact, we’re going down.

The speaker not only inhabits the space between races and cultures, but he also floats between the present and the idea of a bottomless future of pending doom.

While race is not the central focus of the collection, there are notable moments that highlight its role in the speaker’s idea of where he belongs. In “The Melting Pot in Housewares Has a Slight Crack” the speaker declares:

I say the word assimilation like a blade

of grass bending. Always bending.

The line break sharpens the edge of the comparison, encouraging the association of a knife. The sentence turns, however, to reveal that the blade is a leaf of grass in a position of perpetual tension and compromise—perhaps resisting the anonymity of the lawn, or ducking to avoid being cut off. Through this expertly rendered simile, we understand the speaker’s complicated and sometimes painful relationship with the formation of his selfhood.

The strange interrelatedness of disparate things makes this collection work. Olzmann situates his speaker with two feet on the ground, but with an eye fixed on the cosmos and a hand extended to the bottom of the Great Lakes. He casts a gigantic net that captures and connects tangible elements of the earth to orbiting abstractions that help us make meaning in our fleeting lives. In Mezzanines, Olzmann creates a mythic and modern universe that skillfully suspends us in the moment and radiates with light. ![]()