print preview

print previewback DAN O’BRIEN | Visitations

Director’s Notes

Rinde Eckert

Time and money were limited. The performers were, for the most part, not primarily stage performers. The spaces in which the works would be performed were not theaters, per se. The two pieces were not thematically related. These were the problems to solve in staging both The War Reporter and Theotokia as one evening of opera.

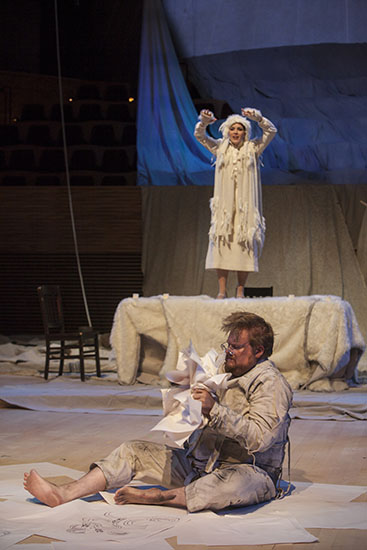

We began by contemplating the various aspects of the two worlds, asking ourselves what characteristics they shared, what materials seemed to belong to either world. Since apparitions were a feature of both operas, the notion of visitations was the obvious thematic link. The operas also shared a common austerity of setting. It was easy to imagine the protagonist of Theotokia as institutionalized, a sequestered schizophrenic in a rubber room, imagining ice caves and snow-bound peaks as he conjured his Yeti Mother. The austerity of Theotokia’s environments seemed to resonate with the austerity of the blasted arenas of The War Reporter—Mogadishu’s rubble and the frozen waste of Resolute, for example. So a kind of desertification, a uniformity of color and texture, seemed appropriate for the setting of these two operas. Materials suggested themselves: a pale canvas (desert sand, snow, parka, flak jacket,) paper (the scribblings of the schizophrenic, the windblown detritus of the urban ruin), boxes (broken walls, ice blocks). There was the notion of the institutional: the asylum of Theotokia, the military-industrial machine of war, journalism itself.

So we covered the stage in gray drop cloths, littered the floor with paper and apple boxes, and placed a table in the middle of it all as a singular stable element (institutional artifact, altar)—a solid thing in a malleable world.

|

| From Theotokia. Photo by Joel Simon. |

In each opera, there is a conflict between the world within the mind of the protagonist and the outside world. It felt right to emphasize that difference by using the supporting cast in each as representative of that dichotomy: In the case of Theotokia, the mode of dress was a cross between the simplicity of Shaker clothing and the uniforms of a crew of orderlies. In The War Reporter the dress of the subordinate characters was meant to suggest a covert government organization.

There is a somewhat cinematic character to these operas, moving quickly from one scene to another, from past to present, from the all too real to the fanciful, from Mogadishu to Columbia University to Johannesburg to Resolute, from a cell to an ice cave to an ordinary house. In addition to suggesting these changes of place by the arrangement of the elements on stage and the additions or subtractions of clothing, we employed projections. They alternately functioned as captions, as architectural suggestions of specific places, as metaphor, and in the abstract as enhancements of mood. They helped to make rapid transitions less jarring or cumbersome.

By all these means, we managed to stage each opera as a singular event while encouraging associations across the divide. The drop cloths and projections allowed us to define an “acting area” on stages that were primarily designed for concerts. Through the manifold repurposing of simple materials (boxes, paper, chairs, table) we were able to suggest an exotic world or a very ordinary one. We could imagine ourselves in the middle of a chaotic war, in the living room of a fraught hyper-religious mother, at a party at Columbia University, or in an ice cave in the mind of a schizophrenic.

One added wrinkle was the difficulty (the lack of time) of memorizing this difficult score. We solved this issue by introducing the idea of hymnals in Theotokia and dossiers in The War Reporter. This allowed our concert singers to feel at home (with score in hand) while still maintaining their theatrical roles.

Each of these operas is large for its size. The themes are dynamic: God, war, religion, sanity, morality, and the vanity of it all. The emotional geography alone, not to mention its challenging musical sweep, makes Visitations a formidable affair. Luckily, we had an extremely talented and particularly intelligent cast. What they did in the short time we had was something of a miracle. ![]()

![]()

Rinde Eckert is a writer, composer, singer, actor, and director whose music and music theater pieces have been performed throughout the United States and abroad. His work includes And God Created Great Whales, winner of an Obie Award, Horizon (Black Anvil Productions, 2007), winner of a Lucille Lortel Award and Drama Desk nomination for Outstanding Play, and Orpheus X (NoPassport Press, 2012), a 2007 Pulitzer Prize finalist. In 2012 he won a Grammy Award for Best Small Ensemble Performance singing with eighth blackbird and Steven Mackey on Lonely Motel—Music from Slide, for which Eckert wrote the lyrics. He is the recipient of a 2009 Alpert Award for theater work, a 2007 Guggenheim Fellowship in composition, and a 2005 Marc Blitzstein Memorial Award for lyricist/librettists from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He is of the inaugural class of Doris Duke Performing Artist Award winners (2012).