print preview

print previewback LAURA VAN PROOYEN

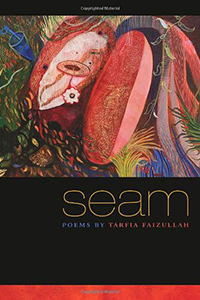

Review | Seam, by Tarfia Faizullah

Southern Illinois University Press, 2014

|

“Why call any of it back?” Tarfia Faizullah asks in her award-winning debut, Seam. Why take brutality head-on, confronting the past where over two hundred thousand Bangladeshi women were raped in the liberation war? Faizullah’s fierce book of poems stands as the answer: because power lies in the telling. Because, as Gregory Orr posits, “Trauma, either on an intimate or a collective scale, has the power to annihilate the self . . . And yet, the evidence of lyric poetry is equally clear—deep in the recesses of the human spirit, there is some instinct to rebuild the web of meanings . . . ” In Seam, tightly controlled poems emerge from that impulse to create space where, through the experience of trauma, we come to some understanding of grief, violence, loss, survival, and the self. This collection weaves together stories of grandmothers, mothers, sisters, and daughters affected by catastrophe, and reveals a speaker grappling with her own faith and identity. In lyrical moments both direct and haunting, these poems expertly twine and intertwine imagination and memory and refuse to turn away from the disturbing seam where lives are both joined and torn.

The opening poem, “1971,” introduces Faizullah’s gift for the deft line and command of the evocative, precise image. This five-part poem revolves around the speaker’s grandmother and mother at the time West Pakistan launched a military operation against Bengali civilians. The women’s stories twirl through time and place, threading together recurring images of “oil,” “water,” “stone,” “light,” “diamond[s],” “bayonets,” and “khaki-clad bodies.” References to “green” permeate the poem, evoking lushness, serenity, and nourishment, but repetition generates a kaleidoscope-effect, where the familiar shifts to take on new and alarming meaning. We discover “A Bangladeshi woman [who] catches the gaze / of a Pakistani / soldier,” and whose “sari is torn / from her.” The narrator’s mother tells the story of her own mother bathing, an intimate ritual in counterpoint to the rape of that woman whose sari is not folded but torn:

She bathed the same

way each time, Mother says—the torn woman curls

into green silence—first, shewould fold her sari,

then dive in—yes,the earth green

with rain, the water,green—then she would

wash her face

until her nose pin shined, aha re,

how it shined—his eyes, green

—then she would ask me to wash her back—

the torn woman a helix of blood

—then she would rub cream into her

beautiful skin—the soldier buttoning

himself backinto khaki—

The green of the soldier’s eyes is incongruous and unsettling, becoming in one sweep a color infused with danger. Furthermore, the abundance of green produces a cinematic backdrop that highlights the jarring contrast of red in “a helix of blood,” then the return to “khaki,” a color by now associated with oppression and threat. This poem, like many in the book, fuses image and meaning, subtly but viscerally increasing the tension and shock of violation. At the same time, the jagged and shifting lines oscillate from reverie to harsh recollection, producing instability that suggests the mother’s hesitancy to remember—a resistance answered by the assertion: “yes, call it / back.” In the poem’s final section, we discover that the speaker intends to “research the war,” and we follow her journey across oceans and personal gulfs as she sets out to gather stories about what happened in 1971.

As a Bangladeshi American woman from West Texas traveling to her parents’ homeland, the speaker has more than one “crisis of faith.” Arriving in Bangladesh, she feels displaced and divided: the “land cannot claim / such cloudy veins, these / long porous seams between // us still irrepressible—.” When she takes her place among a “dark horde of men / and women” who look like her, she is “ashamed / of their bodies that reek.” While in Dhaka for her grandmother’s funeral, the grieving speaker recalls receiving the news:

Grandmother, in Virginia, I cradled

the phone to my cheek and stood over the darkskillet, waiting to turn over another slice

of bacon to slip into my mouth, knowingwell that that sin, too, like so many others,

would dissolve once I willed it to.

The speaker’s honesty reveals both her strength and vulnerability. She courageously dives into the pool of self-interrogation, where bias and a willful embrace of “sin” become mirrors that warrant reflection. As she contends with her personal and cultural identity, the speaker also questions her role in her research, how she has “the right to ask anything / of women whose bodies won’t / ever again be their own.”

At the heart of this book lies a series of poems structured as interviews with birangonas or “war heroines” who survived the atrocity of rape, and whose government thrust them into an uncomfortable spotlight. The speaker takes the position of the interviewer, a more detached than personal stance that creates protective distance. Each of the eight poems bears the title “Interview with a Birangona,” the repetition uniting the women’s collective experience. Yet, the generalized title allows for anonymity and provides a powerful space in which the poet records answers to direct questions, such as: “What were you doing when they came for you?” Faizullah handles the women’s responses with lyric precision and refuses to shy away from details that haunt and disturb. One women tells of “a rope steady around my throat, ” another of the soldier who says “Kutta” only later to “realize / it is me he is calling dog. Dog. Dog.”

Interspersed among the interviews, we find a series of second-person poems, “Interviewer’s Note[s],” where the speaker adopts the distant point of view in order to process the intensity of experience. These poems deal with the present through reflections of the past, and raise the crucial question, “It is possible to live without / memory Nietzsche said but / is it possible to live with it?” For the speaker and for the women in the book, living with memory proves difficult, but for the reader, their potent visions effectively sear the mind.

In our present moment, when headlines daily highlight misogyny and violence, when brutal acts against women persist, Tarfia Faizullah’s impressive debut strikes a tender nerve. These exquisite poems work their way into the psyche, forging a consciousness of troubling loss. The poems demand that we look squarely in the face of terrible truths; yet this book revives the self by retelling, by creating urgency to understand brokenness and grief. Seam does not abandon us in despair. This book is fueled by courage. Faizullah illuminates even the darkest places—these poems turn toward the light. ![]()

![]()

Tarfia Faizullah is the author of Seam (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014), which won the 2012 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry’s First Book Award. She is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, scholarships from Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and a fellowship from the Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop, among other honors. Her work has appeared in Blackbird, Ploughshares, The Southern Review, and American Poetry Review. Faizullah is the Nicholas Delbanco Visiting Professor of Creative Writing in poetry at the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writer’s Program, a writer-in-residence for InsideOut Literary Arts Project, and a poetry reader for New England Review. She is an MFA graduate of the creative writing program at Virginia Commonwealth University.