ELIZABETH KING

The River Then and the River Now

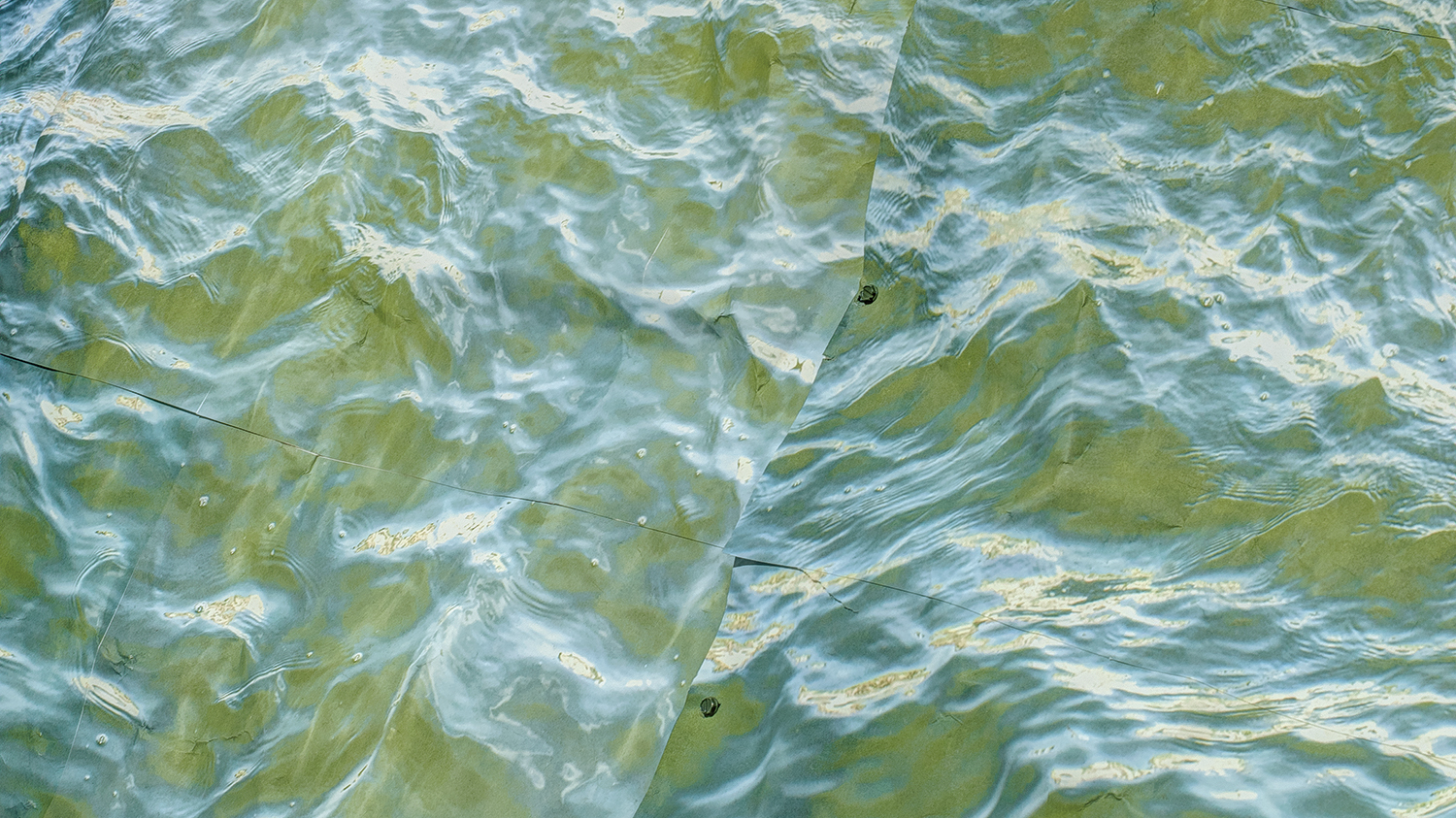

Myron Helfgott’s recent portrait of the River Seine, Water, is one of the best sculptures he’s made. He took three snapshots of the river, blew them up on a grid of forty-eight sheets of 8½ x 11-inch paper, and printed them on his home printer, for a seven-foot-wide panorama of the surface of the water, actual scale. Supporting the image, banked at the same camera angle, is his hallmark wooden scaffold, crafted with architect-tight cross joints, its own grid in three dimensions. The water is choppy and reflects a hundred shades of Parisian blue. He scrunched the individually printed sheets up and only partly flattened them before mounting, so the paper is choppy too and reflects a hundred shades of gallery light. Which light is real and which is photographic? What’s a wave and what's a wrinkle? An image of water at close range: no shores, no frame, the paper extending beyond the support; fluttering edges mimic the windy moment of the shot. One strolls around to see the scaffold, and goes from the straight-faced illusion of watery surface and depth to an equivalent depth of contrivance and craft. A thing made of opposites: the near-comic thrift to capture and size the picture, the elaborate stretcher strong enough to support that volume of actual water. Myron once said, “Painters always want more of the hereness of sculpture, and sculptors always want more of the thereness of painting.” The sculpture tickles itself even as it walks a tightrope over the chasm between truth and bluff, object and image, fixed and fluid, lyric and burlesque. The river then and the river now.

Myron is among the most original sculptors on the American scene. He taught in the sculpture department at Virginia Commonwealth University for thirty-five years. It was a hands down privilege to see him in action as a teacher. No one could predict what he would say in a critique. He loved pointing out things that made a work good in spite of the artist’s intent. Students learned to pay attention to slips and mistakes and visiting angels. He taught all of us about the demands and the gifts of history, how it pushes us like the wind at our backs. Borges, Beckett, Frisch, Calvino, Brodsky—his thinking is suffused with literary form. His love of argument, his pranks, his ethics, his animal energy, his idea of what an art school does—the department sailed to its national reputation on his intellectual momentum. “What is the difference between subject matter and content?” he would ask. “In dreams begin responsibilities,” he would remind us, quoting writer Delmore Schwartz quoting Yeats. He went home from school for lunch every day and worked in his studio. “When I see something I really like, I either have to copy it, or eat it.” How do we measure constitution and physical energy in human achievement? Myron, who works like a horse at seventy-eight, is in his studio every day. He’s making the best work of his career, right now..

Elizabeth King’s work has appeared in permanent collections in the U.S., including the Hirshhorn Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Dartmouth’s Hood Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Most recently, a mid-career retrospective entitled “The Sizes of Things in the Mind’s Eye,” curated by Ashley Kistler, traveled to five museums and art centers in the US between 2007 and 2009. She is represented by Danese/Corey in New York. King earned MFA and BFA degrees from the San Francisco Art Institute. Her awards include a 2014 Anonymous Was a Woman Award, a 2006 Academy Award in Art from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a 2002 Guggenheim Fellowship. King is the author of Attention’s Loop: A Sculptor’s Reverie on the Coexistence of Substance and Spirit (Abrams, 1999). She is currently finishing a second book with coauthor W. David Todd of the Smithsonian Institution: a study of a Renaissance automaton in the Smithsonian collection and the legend behind it, entitled A Machine, a Ghost, and a Prayer: The Story of a Sixteenth-Century Mechanical Monk. The monk is the subject of her shorter essay published in Blackbird in 2002, “Clockwork Prayer.” She is a professor of sculpture at Virginia Commonwealth University.

poetry

poetry fiction

fiction nonfiction

nonfiction gallery

gallery features

features browse

browse