print preview

print previewback CHELSEA GILLENWATER

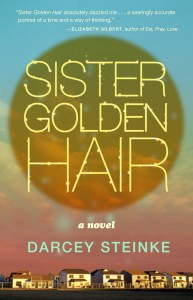

Review | Sister Golden Hair, by Darcey Steinke

Tin House Books, 2014

|

Darcey Steinke’s fifth novel, Sister Golden Hair, a coming-of-age story set in the 1970s, takes its name from a 1975 song by the band America—a dreamy, upbeat track about a relationship that never quite finds the right wavelength. The lyrics in the original song—I been too, too hard to find / But it doesn’t mean you ain’t been on my mind—suggest a stalled narrative, a speaker reluctant to act, and a widening disconnect between reality and desire. Sister Golden Hair revolves around those themes, and Steinke fixes our attention on characters mired in disappointment, constantly trying to reshape their identities by moving in regressive, circular patterns. They often spiral, directionless, without a clear sense of where to turn, and Sister Golden Hair crackles with their desperation and loneliness, allowing us to witness their growth in barely perceptible increments. The characters, drawn so complexly and vividly, wobble in a way that makes them feel alive, and Steinke’s sharply rendered details invite us into the anxious, claustrophobic world of a family stuck in place.

Even in their darkest moments, Steinke’s characters channel hypnotic energy. From the opening pages, Sister Golden Hair evokes a charged, darkening sense of summer: “There was glamour,” twelve-year-old Jesse says, “in the way heat slowed my body down and penetrated every moment with languor.” Steinke layers narrative and imagery in an intoxicating mosaic, blending the surreal with the sublime, the mundane with the monstrous, all amounting to a pitch-perfect examination of adolescence in all its gloomy, transformative power. Our narrator, Jesse, aware of her rapidly approaching transition into “womanhood,” practically storms through the world of the novel, a landscape that expands to capture both the innocence of childhood and an undercurrent of agonizing uncertainty. Jesse regards her future with both fascination and fear, and Sister Golden Hair manages to infuse every scene with the bizarre pull of both; danger and eroticism fork through this novel like lightning.

Steinke heightens the stakes by making even the smallest moments glow with startling spiritual depth. Her characters connect to the world around them in a way that cuts deep; they want to be tied to something bigger, something that they can rely on to guide them. The novel begins with Jesse’s family moving across the country after her father renounces his profession as a pastor, and his crisis of faith pulls the rest of the family into a tailspin of uncertainty as they begin to search for a new home and a new sense of stability. While his wife longs for permanence, for a respectable, affluent home in a nice neighborhood, Jesse’s father has already begun to resist such traditional trappings: “We were, he had told me with great enthusiasm, in a period of devolution, unlearning what we knew.” While her father sees this new chapter as freeing, Jesse longs for a time when her place in the world felt sure: “I thought about our life before we left the church . . . We were at the center of what I thought of as THE HOLY, and our every move had weight and meaning. But out in the world away from the church, we floated free.” The family eventually settles in Roanoke, Virginia, in a small neighborhood of duplexes that Jesse likens to “army barracks,” but their new home feels impermanent, temporary. Other tenants come and go, but Jesse remains, unable to free herself from her parents’ insecurities. Without an obvious source of security or reverence, Jesse begins to test relationships beyond the insular circle of her family, pulling herself gradually out of the shell of childhood.

The chapter titles, named after various characters in the novel, chart Jesse’s fixations—among them her sexy, alluring neighbor Sandy and a strange, hyper-confident girl named Jill who takes care of her younger siblings after her mother disappears—and all of them provide her with a fluid frame of reference for her evolution into womanhood. Jesse places an intense, quasi-spiritual emphasis on her idols. When she identifies Sheila as the most effortlessly popular girl in her class at school, she thinks, “Let her instruct me, like Jesus, from the inside.” In one scene, Jesse goes into her neighbor Sandy’s house and begins to try on her clothes, studying the mechanics of being “grown”: “I tried a sort of chaotic walk that Sandy used as she moved over the lawn . . . I walked back and forth in front of the mirror, slopping my body around as if it were liquid in a bucket, but the bathroom was too narrow to get a real feel for the full sequence.” Jesse longs to feel confident about herself and her future, but her efforts often only make her feel more childish and stunted in her body.

Her exploration of the physical world plays a huge part in forming her identity, and she finds objects and bodies charged with meaning. She worships her favorite books, various objects in her room, girls in her class, and the alluring villains on the soap opera Dark Shadows. By studying the external world, she believes she can make her own body obey her will: “From practicing, I knew the pose I wanted to present when I stepped on the bus. My chin had to have a delicate look and my lips had to be relaxed and slightly parted. I wanted to look mysterious like a Victorian heroine, with pale cheeks and sunken, glittering eyes.” She tries on many versions of femininity: the sickly Gothic maiden, the effortless Playboy Bunny, the aloof mistress. While none of them quite seem to fit, she finds power in the images. Once the effect fades, her discomfort sharpens again, and she once again feels ill at ease in her own skin.

That deep-rooted anxiety propels much of her narrative. Sister Golden Hair mythologizes girlhood as an enchanted, long ago time, something unreachable and unknowable even while Steinke’s characters remain trapped inside it. Jesse views her adolescence as something to escape. Looking into a mirror, she says, “[if] I stared long enough I could convince myself that I had nothing to do with the body before me; it was like I resided someplace else entirely and this body was just a puppet that I controlled.” She often imagines puberty as violent and horrifying, her slow transformation into a “skinny monster.” Stories and images briefly allow her to seize control of herself again, but Jesse also learns that words can be reductive, stripping real people of their lived experiences. She tallies up all her female classmates who have left school only to become the figureheads of imaginary scandals: “It was not unusual for girls to disappear, to turn into stories, but it was rare for them to come back, to change back again into girls.”

Much of Sister Golden Hair’s power comes from Jesse’s omnipresent dread of falling prey to something; she remains aware that the world has a way of claiming young women and turning them into something else entirely. Physical relationships make her leery: “Men, it wasn’t hard to see, ran everything and once a girl got breasts and all that went with that, men had wizard power over you, they could make you do anything they wanted.” The novel takes us through several encounters that illustrate both the thrill and alarm of Jesse’s budding sexuality. Danger and sex seem inextricably linked, and Jesse worries that falling too far could mean losing something essential about herself: “I clenched my fists and stuck my fingernails into the palms of my hands. The slight prick of pain reminded me that I was substantial, that I wasn’t blowing away into the dark.” But Steinke treats eroticism as a neutral force, another avenue to self-enlightenment, and a form of energy that directs itself more inward than outward, a kind of “longing . . . not explicitly aimed at anything.” Sex, for her characters, creates moments of potential, enabling them to forge relationships that can help crystallize their own identity—or consume it entirely.

Throughout Sister Golden Hair, the measured, lyrical prose keeps us grounded in those small moments of trauma, and no matter how dark the subject matter becomes, Steinke always finds a glittering silver lining that helps the characters hold onto themselves and onto hope for their future. Steinke challenges the traditional coming-of-age narrative by prolonging the transformative arc of adolescence, and Jesse manages to find fleeting certainty, moments where the world inside her body and outside the church seem to make sense, to cohere into a story “intended especially for me.” But Jesse learns that survival often means fragmenting herself and changing into something new. She does not need to discover her identity in a single moment of epiphany—instead, she learns that she is something unfixed: tender, beautiful, and more than a little dangerous. ![]()

![]()

Darcey Steinke is the author of the memoir Easter Everywhere (Bloomsbury, 2007) and the novels Sister Golden Hair (Tin House Books, 2014), Milk (Bloomsbury, 2005), Jesus Saves (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997), and Suicide Blonde (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1992). Her books have been translated into ten languages, and her nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Boston Review, Vogue, and Spin Magazine. Steinke has been the recipient of both a Henry Hoyns and a Wallace Stegner Fellowship. She has been Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi, and has taught at the Columbia University School of the Arts, Barnard College, The American University of Paris, and Princeton University.