print preview

print previewback LAURA VAN PROOYEN

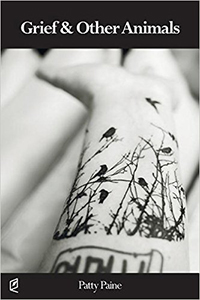

Review | Grief & Other Animals, by Patty Paine

Accents Publishing, 2015

|

“We don’t get to choose / what breaks us” declares Patty Paine in her second full-length collection of poems, Grief & Other Animals. In this book, however, we discover not a person broken, but a woman navigating the relentless and cyclical nature of suffering. These spare, tightly woven poems take on “[the] sudden / onrush of grief” while surging with the “constant / undercurrent of sorrow.” Divided into three sections, each one prefaced by a well-chosen epigraph, the book begins three months after the crushing loss of a partner to addiction. Section II examines the speaker’s deep history of pain as revealed through memory and her mother’s death, while Section III attempts to reconcile the experience of the past in relation to the present. Paine’s gift for the deft line and for arresting imagery keeps the subject of grief, which in its very nature is repetitive, from feeling overplayed. These poems, always precise and direct, scrutinize loss both as overwhelming void and as persistent presence.

A raw and recent anguish permeates Section I. In the opening poem, “Merciless,” the speaker projects her anger onto pigeons that continue to arrive, “still expecting / a scribble of seed along the sill” months after her partner’s death. Her impassioned response to their habitual need reveals her own struggle to cope, especially when reminded daily of her partner’s absence:

How not to hate their relentless

innuendo, their inexhaustible need

to return? The hand that feeds you

is no more. Take your stupid swagger,

your useless iridescence, alight

yourselves, be gone.

The blunt question and thudding directive highlights the speaker’s futility, her resentment that the world continues to go about its business despite her acute suffering. We sense, too, that the sharp edge of grief is made all the more painful, having lost her partner when he “hit the black ice / of addiction,” an event that cut her “razor clean.” She does not, however, lash out against his self-destruction, or even directly against death, but targets the feeling she’s forced to reckon with: “Grief, intransigent / bastard you, ants marching // my counters, every day I kill / you, every day you march again.” The speaker’s voice is strong and clear, an impressive stance of certainty in the wake of destabilizing pain. Her footing feels sure, especially in poems that record events in the form of journal entries, noting specific months, days, and years, suggesting a desire to create order in spite of the disordering chaos of death. “Grief Diary, Day 107” recalls the couple refusing shelter from a hurricane and explains, “We needed our beauty hard, / our danger real,” but the speaker reflects on the scene with new understanding: “I see now, / even then, you were leaving // your body, nothing could hold you; / nothing left to save.” In these tense, terse poems we sense an urge to recall with specificity, to affirm and process truths, even if those truths are difficult in retrospect. The voice rings with clarity, and the images arouse the effect of grief, both jabbing and numbing.

Section II opens with stark revelations that portray lives influenced by a long history of trouble. In “Erasure as Explanation” we find the speaker’s mother and father “Night after night” in “drunken cadence,” while “Each morning” arrives as “the color of bruises.” The poem turns from disclosing the details of a violent home to reveal the equally complicated life of the “you” who we understand to be the speaker’s partner:

. . . you told

me you were seven

your mother left you

at his house every day.

You see yourself

going back, door opening, muzzle

flash, his face

a thousand shards.

We thought this joined us,

we were marked

with the same [ fucked up] brand.

The speaker’s loss becomes even more heartbreaking once we understand that a shared experience of abuse drew the couple together. The bond of suffering could not protect her from further pain. Stylistically, erasure as a form highlights the poet’s attempt to make sense of turbulent circumstances. Deleting the unnecessary distills focus and gives power to choosing what will remain, a way of taking control when losing a partner to addiction and witnessing the “mother’s slow dying” threaten to keep the speaker in a spiral of sadness. Her strength grows and transforms into moments of healing, as in “Memorial” where she assures us, “It gets better, dear reader, the wailing / I promise you, will someday break / into song.” Her direct address offers a flash of relief, recognizing that bearing witness to grief can be taxing for the listener, too. We are drawn close to the speaker who includes us, who glimpses hope after months of despair.

The intricate and complicated process of healing moves toward acceptance in Section III. In contrast to the anger that opens the book, we find the speaker reverently reflecting on animals and objects that serve as totems of loss. When her partner’s cat pressed its face against her neck, “for a moment [her] mind went / magical.” The avocado seed planted by the deceased “blossomed like a memory” and our speaker vows to “try not to kill [it] / with love.” Moving toward healing, however, is far from a linear process. “Derecho,” one of the collection’s most remarkable poems, presents a notable departure from the other poems’ tight lyrics. Here we find grief in fragments, in disjointed stanzas that start and stop, that change course in an attempt to get the story right. Ironically, the poem’s disjunctive moves create a space where the speaker’s voice feels secure. “Name it” she says, “Begin again.” Her commands become the fixed points around which the details of her life swerve. The perspectives shift. She addresses the self, the reader, and directs questions to the deceased. She is insistent:

Some days it comes like this, fragmented

and untidy.Persist.

Persist.

Persist.

There’s power in naming what haunts us. The speaker’s urge to recall, to nail down details, signals an authoritative move. She speaks from a place of strength, even as she attempts to convince herself that “grief humbles, / grief softens / . . . It must. / It must. / It must.”

Spare and intense, these carefully wrought poems show impressive emotional depth and range. They do not seek closure, but offer an honest portrait of suffering. This strong, solid collection recognizes grief as a complex and unresolvable experience, where pain can rush in and recede like a tide, where it can sting like a fresh cut or for days dully throb. In Grief & Other Animals, Paine creates a voice we trust, a woman who speaks from hard-won knowledge. She shows us the imperfect path toward healing and acknowledges that the process will never be over: “Sorrow, I accept you, how I’ll carry you / the rest of my life. I accept // you’ll sharpen yourself / endlessly.” Paine gifts us with a voice that is resilient and smacked with truth. ![]()

Patty Paine is the author of three collections of poetry. In 2011, her collection The Sounding Machine (Accents Publishing, 2012) won the Accents Publishing International Poetry Contest. Her poems, reviews, and interviews have appeared in The Louisville Review, Gulf Stream, The Journal, and other publications. She is an assistant professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University Qatar where she teaches writing and literature, and is the interim director of Liberal Arts & Sciences.