print preview

print previewback KATHRYN LEVY

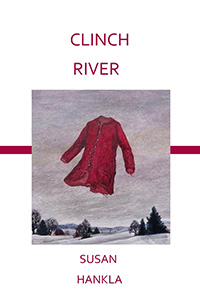

Review | Clinch River

Susan Hankla

Groundhog Poetry Press, 2017

|

Many years ago, when I first read Susan Hankla’s work, I found myself laughing out loud. But it was a complex laughter, mixed with terror and wonder at this odd and unsettling voice, which is unlike any other writer I know. So it was with great eagerness that I opened Hankla’s debut poetry collection, Clinch River.

What I found there surprised me, even though I thought I was familiar with this unique poet. The constantly shifting diction in Clinch River, the unexpected imagery, and the ambiguous terrain Hankla explores made me dizzy. Hankla is a writer who always keeps her readers off-kilter, who takes us places that feel both familiar and surreal. Her dream life is inextricably intertwined with quotidian, often comical details, her intricate metaphors enriched by the distinctive twang of Appalachia.

In Clinch River Hankla displays a microscopic eye for detail and an acute ear for the idiosyncratic voices that surround her, but it is her vertiginous imagination that makes this book so compelling. The work, like all truly original writing, is impossible to categorize. It’s as if a Language poet were melded with a Flannery O’Connor character, and transformed into a peacock. Not simply some dazzling peacock, but one with drooping feathers who has to remember to take in the laundry.

This roller coaster world is perhaps best exemplified by the book’s first poem, to which I can only do justice by quoting in full.

The Sweater

She didn’t see the sweater on her back

unraveling as she walked away from home,

didn’t know its cables

snagged on winter’s thorns

so scarletly,

delighting squirrels and magpies.

Didn’t know this shredding sweater

was her shining raiment,

didn’t know she’d grip its last pearl buttons

to barter for milk, for bread.

Didn’t know how hard she’d have to work graveyard

in the store of winter long johns

or that she’d see the one red pair

swinging on its hanger, like a quadriplegic soldier,

like a clothespin dolly on the line from girlhood.

Or that in buckets of wash water she’d see herself,

and that she couldn’t stop moving, flying

back through the years,

until the tree of her sweater’s remains

rained down apples,

at first rotten, then merely bruised,

and then, finally, she tray-packed Golden Delicious,

standing in line

with others at the orchard.

The insistent music, the metaphoric leaps, the play with language, and the remarkable amount of territory Hankla covers in a relatively short space are characteristic of the best work in this volume. With the narrator we fly back and forth through the years, often ending up dazed and stranded “in line / with others at the orchard.”

I look at the two similes in the third stanza of this poem and wonder how many writers would immediately follow such a disturbing image as “a quadriplegic soldier” with the childlike diction and imagery of “a clothespin dolly.” But that sort of unexpected juxtaposition is at the heart of this book.

Appropriately enough for a first poem, “The Sweater” introduces many of the obsessions that define Clinch River. The lost and found world of childhood resonates throughout the book, and from different angles Hankla explores the unraveling of much that we love, the constant struggle for bare necessities, and the detritus of a life, sometimes “tray packed,” sometimes swinging on a clothesline.

The narrator begins her journey in Appalachian coal country, surrounded by hardscrabble lives and startled by unnerving daily discoveries, from her first sexual awakenings to the tip of a character’s finger “lopped off” while chopping wood, leading to the half-humorous, half-rueful line, “It’s going to be hard to write cursive from this day on.”

We encounter the mother who cans dirt, but not just any dirt:

The dirt my mother canned could not be just any. No.

It couldn’t come from hookworm plots

where the dogs lolled. She had to take a bus

to the far rough edges of county—

to a forgotten graveyard, where her people

lay down in their satin.

That was Indian dirt she canned.

And after it cured in dark ground,

she’d dig it up toward the end of the month

to make cookies

we’d eat

when we were down to Crisco

and ketchup.

The unusual image of the mother canning dirt and using it to bake cookies is a vivid metaphor for poverty, but Hankla pushes the poem further, reminding us of the everyday products, Crisco and ketchup, that have to be scrounged from the kitchen simply in order to survive.

The book is filled with slightly askew characters like that mother. Among them is the father who throws the speaker “to the biggest wave / to teach her to cry”; Miss Reed, “prize-winning educator,” who shows her students a lynching photo, “for our good”; and the young boyfriend, Junior, who decides to drown his souvenir alligator in the Clinch—the same river that engulfs a suicidal young couple and a pregnant girl.

And of course, this being the South, there are the pervasive echoes of the preachers—or are they carnival barkers?—as in “If You Believe on Him, You Will Not Need Fire Insurance”:

My God is bigger than yours. My sheets are whiter.

Life is my china pattern. Death is my charger.

Jesus my change.

These goblets are grails.

The Tupperware burps His Name.

I suppose one could describe that last line as a twisted colloquialism, but Hankla’s linguistic approach is more intriguing than a mere negotiation between colloquial and figurative language. She has her head in the kaleidoscopic clouds, but at least one foot always kicking at the dirt: “I’ll sing the song that’s part breath, part coffee. / I’ll be that bluebird that creaks on russet hinges outside the door, / that pecks at the suet bell on the ground.”

Aside from the sometimes tortured, sometimes bemused narrator, the figure who looms largest in these pages is Glenda, a schoolmate, half-imagined from the start, who remains in the town that Hankla leaves but can never quite leave. Glenda has one damaged eye and also shares some secret vision with the speaker, as in the fascinating poem, “How I Know Glenda”:

At school I touch her clammy hand, then give her

the bag of vitamins the town pharmacist, my father,

says to take her. And I see that one eye has a black dot,

where a BB’s lodged, that her brother shot, missing a grouse.

So Hankla provides Glenda with a wide range of offerings from “Hostess snowball twins,” to “two newborn mice who choked on dust bunnies,” to “bikini panties embroidered with wolves’ lolling tongues.” Most of all she gives her a voice that is intensely alive, perhaps most so in the poem “The Boy in the Red Shirt”:

The principal’s messenger

hands our teacher the roster of scores,

then plods back across gravel and dirt.

And into the trash of pencil dust

and blackening fruit skins,

go our IQ test results.

“What did it say?” Glenda yells from the window.

“Don’t know,” calls the boy. “Can’t read.”

“Marry me,” yells Glenda.

The ending of this poem, like so many in the book, swerves in a delightful, unexpected direction, provoking once again that complex laughter. But as the world of the book ages, as the unraveling becomes a permanent condition, both Glenda and the narrator are forced into corners of sadness and bleak revelation: “Her copper hair cross-boned with bobby pins, / Glenda pries the lid of the Eight O’Clock coffee tin / where she keeps the sunflower’s face, / to see it’s more like a heart now.”

And what of the writer, Glenda’s restless friend? She surveys her disappearing life, still reliving the past, composing a letter to the husband she has failed in some way, as perhaps we always fail:

You have carried me as a soldier carries one photo.

In squelching mud.

In soot and ash.

Through the slights of a life.

That photo doesn’t change.

But how does time get by with running away so recklessly?

That note of regret for all that has gone wrong, for the dead and for the many people left behind, informs the somewhat quieter tone of the last poems in Clinch River: “I once raked leaves / when I was angry with my mother / and now that memory rakes me.”

This is not to suggest that the arc of the book is a simple or linear narrative—it is too dreamlike and anarchic for that. Throughout Clinch River Hankla expands our imaginative reach in a way that only a truly adventurous poet can. Inevitably, not all the poems are completely realized, and, unsurprisingly for a writer so intoxicated by language, there are times when wordplay overwhelms a poem.

However, those are minor problems. This is a debut that is long overdue and one to be cherished. With each reading of Clinch River I found myself startled anew. Read the book slowly, then read it again—but be prepared for a wild ride, because Hankla’s voice will both delight and sear you. As one of her haunting characters says, “‘I like my own cooking, / even if it burns.’” ![]()

Susan Hankla is the author of Clinch River (Groundhog Poetry Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in Gargoyle, Beloit Fiction Journal, Michigan Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. She earned an MFA in creative writing from Brown University. She teaches creative writing classes at the Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia.