print preview

print previewback MATTHEW PHIPPS

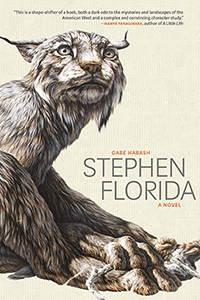

Review | Stephen Florida

Gabe Habash

Coffee House Press, 2017

|

Stephen Florida, Gabe Habash’s tough, smart debut novel, is an ode to the solitude and rigor of college wrestling, its guts and its glory: mats smelling of disinfectant and jittery vomit in locker room sinks; running bleachers and two-a-days and savage rivalries based on arbitrary brackets; hand-meat mashed by teeth, singlets twisted and threatening to tear, fingers in eye sockets, knee joints, and assholes; heartbreak and loss. Stephen Florida is also, at its strongest and truest core, an intricate, book-length study of Florida himself—hypnotic, self-aggrandizing, frequently disturbing, sometimes startlingly lucid—and through Florida’s dumbly savvy voice Habash asks bold, difficult questions about the challenges and compromises that complicate true resolve.

Florida’s singular narration is the heart and engine of Habash’s novel, with all the digressive strangeness and boastful grandeur of Captain Ahab shot through with . . . John McEnroe? “I keep making history like it’s my job to manufacture it,” Florida brags, and his record for the season backs him up. A senior at a small college in Oregsburg, North Dakota, he is the top-seeded wrestler in his weight class, with his sights set on the Division IV NCAA Championship in Kenosha in the spring. Coasting through his classes with a C average, Florida has little time for typical college experiences, shunning nonathletic friendships or romantic possibilities. For him, “food is an afterthought, class is an afterthought, people relationships are an afterthought, hydration is an afterthought, sleep is an afterthought.” When Mary Beth, a girl he meets in his Drawing class, asks him what he plans to do after graduation, he replies, “I hadn’t thought that far ahead.”

Some of Habash’s most interesting writing probes the depths of Florida’s grueling routines, following both his coaches’ orders and his own personal superstitions. We get, for instance, a paragraph’s worth of counting pushups, one through fifty, and a list of ninety-nine names, the only opponents he has lost to since he started wrestling as a boy. Florida’s physical and mental exertions assume the form of mantras or prose poems, ranging from the earthy:

Suicide sprints, jump rope, rope climbing, five times, arms only. Two and a half hours after I’ve started, I’ve finished. I go to the showers and get dressed. I brush the vomit out of my teeth and get my backpack.

to the transcendent:

Wormhole, black hole. Invisible far-off radio frequency. Unknown bloop from the hadal deep. I’m trying to push into a deeper place.

There’s an ascetic, almost mystic quality to Florida, whose motivations never require more than a one-sentence explanation, and for whom the question of why a division championship might be so alluring is beside the point. The forces determining Florida’s life are elemental: “I am only a giant collection of gas and light and will,” he says, as though to reassure himself. “I’m skin and gristle and little water, Stephen Florida without end Amen.”

Florida is tortured by a loss in his past: the death of his parents in a car accident while he was in junior high. An emotionally distant grandmother cared for him through high school, but since her passing Florida is utterly unmoored in the world, save for the college wrestling program that has provided him with material support, structure, and a close-knit, if violent, sense of family.

Of this odd family, Florida is closest to Linus, a freshman champion wrestler whose record is almost as sterling as Florida’s. Linus and Mary Beth are important centers of warmth in this novel, pulling Florida into the world outside his steely, sometimes repetitive monologue of alpha-male discipline. Just as Mary Beth begins to break through Florida’s championship tunnel vision, softening the edges of his character, conflict arrives in that greatest fear of jockish protagonists: midseason injury.

His meniscus is torn during a match, putting Florida out of commission for several crucial months and causing a sort of disassociation that never really stabilizes for the rest of the novel. Emerging from surgery with a stash of painkillers and facing the looming void of winter break with nowhere to go, Florida distances himself from Linus and Mary Beth and becomes obsessed with the threads of violence and guilt he sees around him in Oregsburg, unconsciously replaying the trauma and survivor’s guilt stemming from his parents’ accident. Habash spruces up familiar novelistic psychologizing with the sheer strangeness of Florida’s delusions, which seek out murderous conspiracies among his coaches and teachers, find him wrestling goats in snowy fields, and holing up in his dorm room with a gorilla mask during an apocalyptic blizzard. Habash charts Florida’s decline in harrowing detail, his delivery growing choppier, more fragmented and hazy by the paragraph, until the reader wonders when and if Florida will ever hit bottom, for his sake and for ours.

The surface business of Stephen Florida—his dynamics with Linus and Mary Beth, a few other subplots that feel more like distractions, and of course, the small matter of the division championship—is mostly completed, with varying degrees of reader surprise and satisfaction. The meat of Habash’s project, though, the questions raised by the very existence of a character like Florida—so deranged, so uniquely focused, so troublingly recognizable—linger unresolved, as they must: What does it mean to dedicate an entire novel to a voice so defiantly unliterary, so suspicious of introspection? And what does it mean to identify with such a voice?

Urinating on strangers, picking fistfights for no reason, devoid of remorse, Florida is reminiscent of one of David Foster Wallace’s hideous men: ugly in his specificity, horrifying in his plausibility, and seemingly incapable of redemption (not that he cares). Stacked up against other memorably unlikeable narrators, he lacks the playfulness of Roth’s Portnoy or the hidden softness of Salinger’s Caulfield. He careens, within the space of a single paragraph, from “finding out how the world works, locating its pulley systems, and placing myself in the center,” to emphatically reminding himself—the reader?—to “find your center and fuck it until it’s pregnant with your little babies so they can come out and find more centers to fuck.” Habash takes his place in a decidedly macho lineage of American letters, but his writing rewards those readers willing to push past the locker room tautologies and mat–side gore. In a novel that interrogates the dangerous allure of hubris and examines the depths to which pure dedication sometimes leads, the stakes of Habash’s ambition and his confident control of craft leave the most lasting impressions. I winced, felt nauseous, and even actively disliked Stephen Florida at times while reading it. I confess I have no idea to whom, among my closest friends, I could wholeheartedly recommend this book without a list of caveats. And yet I know one thing without a doubt: I will be certain to pick up whatever Habash writes next. ![]()

Gabe Habash is the author of Stephen Florida (Coffee House Press, 2017). His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and the Huffington Post. He holds an MFA from New York University.