print preview

print previewback HENRY HART

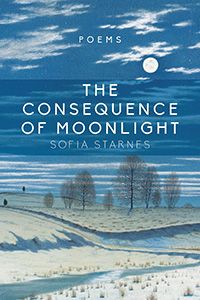

Review | The Consequence of Moonlight

Sofia Starnes

Paraclete Press, 2018

|

|

One of my first encounters with a well-known poet occurred when George Starbuck visited my college in the mid-1970s. Starbuck had honed his craft during the late 1950s alongside Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton in workshops taught by Robert Lowell at Boston University. (Starbuck would later become Sexton’s editor at Houghton Mifflin.) Before he gave his reading at my college, Starbuck agreed to comment on a few poems at a gathering of students and professors. I don’t remember the poem I read, but I recall him objecting to my mention of the moon. He said the moon was a cliché and I should avoid all references to it in future poems. In the discussion that followed, I was relieved that my classmate Louise Erdrich defended the use of moon imagery in poems. As I remember, she said it was fine to write about the moon as long as you did it in an original way.

I mention this anecdote because Sofia Starnes is keenly aware of the way words such as “moon” and “moonlight” can be clichés. (Sexton and Plath were aware of this, too, and often used moon images in startling ways to avoid the sort of criticism made by Starbuck.) The poem that introduces Starnes’s ambitious new collection, The Consequence of Moonlight, invites the reader to join the poet in re-envisioning the moon as well as the sublunary world and the words used—and sometimes overused—to represent them. “Invitation” begins: “Imagine one magnolia in the yard, / a solitary grosbeak out of reach / on a solitary branch.” Like a phenomenologist pondering the intentionality of consciousness, Starnes goes on to say: “Intent, it’s all about intent— / as with the eye, no more surveyor // but a lover in the momentary light.” The “momentary light” leads to thoughts of its source: the sun. Many of the poems in The Consequence of Moonlight are meditations on moonlike mediators that transport the mind to sunlike sources. The poems are religious in one of the etymological senses of the word “religious”—re-ligare—“to bind back.” Starnes’s moon resembles a mediating priest or saint who binds us back to a divine “source of knowledge” and “evidence of mystery,” as she points out in her note to the reader. Like Wallace Stevens in his “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” she invites us to contemplate both the “invented world” of the Creation as well as “The inconceivable idea of the sun” that, paradoxically, allows us to conceive of an ultimate Creator.

The Consequence of Moonlight draws on the scientific, mythical, and poetic properties normally attributed to the moon (it pulls tides, affects menstruation, inspires poetry, enhances romance, causes lunacy), but Starnes’s poems are full of stylistic surprises. “Invitation,” for example, concludes with the moon playing the muse-like role of Robert Graves’s “White Goddess” and inspiring an adolescent girl to imagine: “How green each word [is] outside her room.” In the moonlight of a dark night, the girl apprehends the “green” world of vegetation as a new heaven and new earth made of enchanting “green” words.

Many of the poems in The Consequence of Moonlight chart the sort of dialectical journeys between dark interior spaces and luminous exterior spaces navigated by Christian mystics. One of the best-known poems about the via mystica, St. John of the Cross’s “The Dark Night,” resembles Starnes’s nocturnal poems in numerous ways. To delineate the ineffable journey toward the “inconceivable idea” of God, St. John used metaphors of a “stilled” house at night to represent the contemplative mind, a lover leaving the house “With no other light or guide / Than the one that burned in [his] heart” to represent the soul searching for God, and an erotic tryst between lovers to represent the ecstatic union between soul and God. St. John explains the consequences of this union in the last lines of his poem: “All things ceased; I went out from myself, / Leaving my cares / Forgotten among the lilies.” Starnes’s poem “Tenebrae” recapitulates a similar dark night of the soul in which a person “anxious to explore” the spiritual realm leaves a domestic space, journeys through the night toward a divine light, and returns to the domestic space feeling at least partially redeemed. (The poem invokes the Christian ritual of Tenebrae, which commemorates Christ’s Passion and Crucifixion by extinguishing candles in a church until it is completely dark.)

The central persona who searches for and embodies divine lights on dark nights in The Consequence of Moonlight is a young woman named Elena. Her name is derived from Helen or Helene, which may have come from Greek roots meaning “bright one” or “torch light.” Starnes points out in her postscript that the name may also be related to Selene, the Greek goddess of the moon. Like other figures who make cameo appearances in the book, Elena is a traveler who leaves her solitary life at home, explores the world, experiences enlightenment and transcendence (she “dream[s] beyond the sun,” as the narrator of “Mortality” says), and returns home with a sense of fulfilment. Elena expresses the sort of longing for a mystical “night that has united / The Lover with His beloved” that St. John referred to in “The Dark Night.” She is one of those “restless . . . girls with godly aches,” Starnes writes, who harbors a passionate “wish to be His.”

Elena at first appears to be a light unto herself. In “Whole” she plays maître d’ at a nocturnal dinner party that nobody attends. Her solitary imagination, like the moon, shines most intensely in the dark. Her lack of physical contact with others spurs her desires and fantasies to the point that she “thinks the night’s a harvest bowl, / the moon, a fruit susceptible to bleed.” Despite her isolation, or perhaps because of it, she grows acutely aware of the way the imagination can confuse word and world, fiction and fact, story and history, mind and matter. She matures physically and philosophically as the book progresses. If Elena appears pitiful at the beginning, by the end she has attained the redemptive powers of a spiritual healer.

The inspiration and vision that motivate redemptive journeys are among the “consequences” of moonlight that Starnes celebrates in her book. The title poem harks back to the introductory poem, “Invitation,” but now the moonlit garden is not only green with words; it is populated with imaginary saints who inspire others to embark on contemplative journeys. The goal of these journeys is the same sort of ineffable awe at the mystery of Creator and Creation that St. John expressed at the end of “The Dark Night.” Retraining her vision on the garden, the narrator of “The Consequence of Moonlight” sees something akin to the Rapture: “moonlight bodies storying up our sky.” About this apocalyptic moment, she says: “And so, from word we turn to wordless.” The poem plays variations on the book’s motifs in a way that imitates that most circular of forms: the villanelle. One of the remarkable aspects of Starnes’s poems is their enchanting music. Her poems ponder “the right questions,” as David Bottoms pointed out in a blurb, but they do so with the playful exuberance of the girl who looks out the door of her house, sees a world full of green words, and breaks into song. ![]()

Sofia Starnes is the author of six collections of poetry: The Consequence of Moonlight (Paraclete Press, 2018), Love and the Afterlife (Franciscan University Press, 2012), Fully into Ashes (Wings Press, 2011), Corpus Homini: A Poem for Single Flesh (Wings Press, 2008), A Commerce of Moments (Pavement Saw Press, 2003), and The Soul’s Landscape (Aldrich Press, 2002). Her poetry has appeared in Gulf Coast, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Hotel Amerika, Hubbub, Laurel Review, Madison Review, Notre Dame Review, Pleiades, and Southern Poetry Review, among others. Starnes served as the Virginia Poet Laureate from 2012–2014.