print preview

print previewback WILLIAM BELL

from A Scavenger in France: Being Extracts from the Diary of an Architect,

1917–1919

[British spellings are retained throughout. All images are from sources external to the book.]

Introduction

It has been my privilege during the war to serve as one of the scavengers in certain of the devastated regions of France—clearing up the wreckage after the iron whirlwind had passed over the land; erecting temporary dwellings to replace the demolished homes of the patient peasants; and helping to encourage them to begin life afresh amidst the charred stumps and the cannon-swept ruins of their former happy foyers.

Perhaps it may be well to mention the fact of my non-participation in the active cares of war at a time when the whole world groaned under its imperious demands. But without attempting here to give all the reasons annexed to my neutrality—the question is too complex to be dismissed in a superficial manner—let me say that it was utterly impossible for me to take up work in a munition-factory—in other words, to kill by proxy, with a negligible amount of risk to oneself. Therefore, I went to France as a volunteer to do work, not of national, but of international, importance in helping to alleviate the sufferings of the civilian victims in the War Zone.

My duties as architect with my Unit took me into many corners of France; thus I had innumerable opportunities for discussing with both soldiers and civilians. For five winter months I lived amongst the soldiers in the War Zone at Ham—first with the French, then with the British troops—until the Big Push of March, 1918, sent us all trekking westward upon Amiens . . .

Chapter I

In the Jura

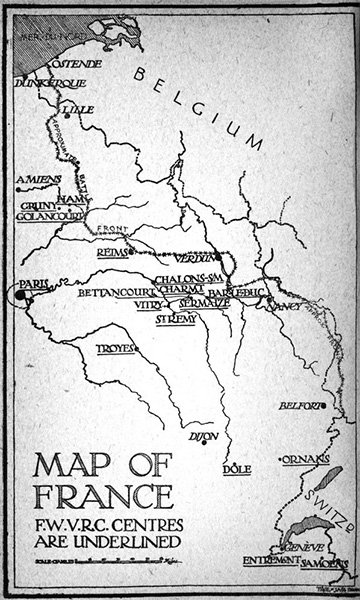

27 May 1917.—Having become a member of the organisation known as the Friends’ War-Victims’ Relief Committee, I arrived in Dôle-du-Jura in the N.E. of France to-day. It was shortly after the outbreak of the war that the F.W.V.R.C. was inaugurated; and in November, 1914, the first handful of members arrived in France to undertake the pioneer work of the Mission des Amis, as the unit is called by the French. This is not the first occasion on which the Quakers have sent a relief expedition to the battlefields of Europe; for, in the Franco-German war of 1870–71, the Society of Friends conducted a similar relief campaign in the devastated regions of France.

|

|

| Friends’ War Victims Relief Committee Centres. Fourth Report of the War Victims’ Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, October 1916 to September 1917, (London: Headley Brothers, 1917), 16. |

|

Our camp at Dôle lies on the edge of the vast Champs de Manoeuvres, about twenty minutes’ walk from our Workshop in town. We sleep in wooden huts of our own sectional type, made and erected by the boys themselves. It is an ideal camping-ground, having a southern aspect, with the various peaks of the Jura Mountains lying to the south-east, and, in the foreground, the town of Dôle, with the great Forêt de Chaux:, 20 miles long and ten miles wide, beyond it. On clear days it is possible to see Mont Blanc and other Alpine peaks, from our camp—the distance to Mont Blanc as the crow flies being some 100 miles. The camp stands at an altitude of about 840 feet above sea-level; and the ground to the north-west gradually rises to a height of 1,120 feet—the summit of Mont Roland being crowned by a Pilgrim Church having a tall spire which is a landmark for many miles round.

It was in August, 1916, that the pioneer group of workers arrived at Dôle to begin operations in the sectional construction of wooden houses for French refugees. The French Government supplies the F.W.V.R.C. with the timber from the State forests gratis; while my Unit gives the voluntary and unpaid labour of constructing the sections, and of erecting the houses in the devastated regions of the War Zone. Formerly the Mission des Amis erected the wooden houses on the actual sites in the destroyed villages, the timber having been sawn up on the spot. But the difficulties of transport ultimately became so serious that it was decided to set up a manufacturing department in the heart of the great timber district of France. The mountain would not come to Mahomet, so Mahomet had to go to the mountain. In other words, a workshop was opened at Dôle, near the wooded mountains of the Jura; and here are now made the interchangeable and demountable sections of our huts. These are transported by rail to the war-battered districts; and our erecting groups on the spot quickly run up the easily-handled sections into two, three or four-roomed huts—according to the needs and sizes of the several families . . .

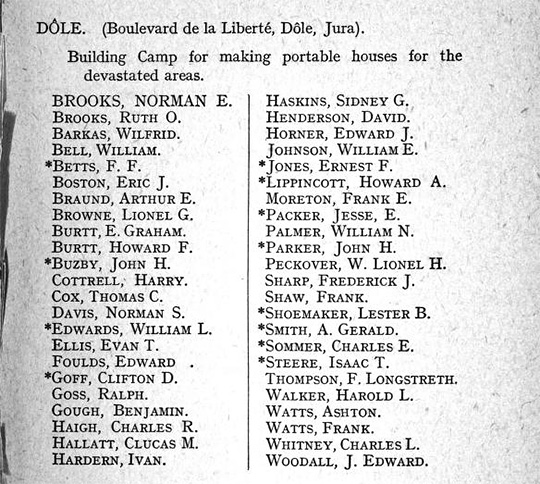

|

|

| FWVRC members, including William Bell, assigned to the building camp at Dôle. Fourth Report of the War Victims’ Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, October 1916 to September 1917, (London: Headley Brothers, 1917), 7. |

|

Chapter II

In the Somme

6 November.-Owing to the sudden departure from the War Zone of the leader of the hut-erecting group at Ham, I was asked to-day to take charge of this work, though I had been originally destined to run the repair group at Gruny. It is mainly because I am an architect, of course, that I have been made responsible for this équipe of American and British workers.

This evening a French officer called at the house to interview me. He had with him the copy qf a letter I had written to my brother, who is in the R.N.A.S., and in which I had asked him to send me regularly a certain magazine; and that he must not in future write w freely about war and peace as he had hitherto done when I was living outside the War Zone. The British Intelligence Department had asked the French authorities to investigate my case, and to report on the result of an interview: I was mildly amused that a harmless creature like myself should be the innocent means of setting in a flutter the military dove-cotes at Amiens.

6 December.—There was another air-raid early this morning, and it lasted for four hours, during which the German ’planes kept coming in relays every fifteen minutes, dropping their load of bombs and returning across the lines without mishap to themselves. Naturally, considerable damage has been done to the town, though the équipe building in which we live has come out unscathed. It is reported that one 'plane had come very low, and flown along the whole length of the main street, all the while a machine-gun was being fired from it on the stragglers who happened to be about at that early hour.

8 December.—I left Ham this morning to return to England on leave, going by car to Noyon, where I had time to loo at the Cathedral, which is a well-preserved specimen of Gothic art, the east end being particularly tine, with its chevet of chapels encircling the apse, and its delicate flying-buttresses gracefully radiating around it.

19 December.—While travelling by train in Yorkshire to-day a pompous-looking individual, resplendent with starch, gold-rimmed glasses, and gold watch chain, was curious enough to enquire to what regiment I belonged, as he had never seen my uniform before. To complete his education, I quietly informed him that I was not in any regiment or army; but that I was a “slacker” who had been working voluntarily in France for the past six months.

He did not become disdainful, however; but further enquired what was my work “before the war,” and what kind of work I had been doing in France. I replied that I had been working as a carpenter making wooden huts until recently, but that I had been put in charge of the group in the War Zone at Ham, because I am an architect by profession.

His surprise expressed itself thus: “But surely a gentleman like you has never been doing carpentering?” I asked him if he was a Christian; and he replied: “Certainly.” Then I reminded him that if the First Christian did not find it beneath his dignity to do carpenter’s work, I certainly did not—more especially as I have seen the untold sufferings of the French peasantry in the devastated areas. No more was said by the good patriot, and there was a glacial silence in the compartment until he eventually got out at his destination.

11 January, 1918.—I set out to-day from Paris, where I arrived from England two days ago, to return to my work at Ham, going by way of Amiens, where I had to wait four hours before my train was due to leave for the remainder of the journey. 'l'his interval from 12 to 4 o’clock enabled me to see the great Cathedral. . . .

In these days of tottering dynasties and shattered policies and disturbances of the “Balance of Power,” the dynamic forces of war have damaged Louvain, Ypres, and Reims to a greater or lesser degree; but so far Amiens has escaped the sacrilegious shells of Armageddon, though the Germans occupied the city for some eight days in the early stages of the war in 1914.

It was Ruskin who called the statuary and carving on the portals of this architectural Queen of Picardy, the “Bible of Amiens.” The “Huns” have therefore not followed their “usual” plan-according to the language of the correspondents of the Daily Mailed Fist—systematically destroying historical examples of art which they cannot carry off as loot; for not one page of the precious Bible of Amiens has been torn from its lovely binding. The world has shed its crocodile tears for Reims: it has not yet been decreed by the God of Battles that the funeral ceremony of Amiens shall also be celebrated.

'l'he zealous guardians of the Cathedral have hidden the West Portals behind sandbags up to the level of the springing of the great archivolts, in order to protect as much as possible from the rigorous fangs of war the glorious statuary that adorns the porches. Sandbags also cover up the portals of the North and South Transepts; and the early sixteenth century flamboyant choir-stalls are likewise cased in a skilfully-designed framework of steel-beams and stancheons supporting layer upon layer of carefully-placed sandbags, ready to withstand the iron whirlwind should the rudeness of its blast threaten the carved oaken treasures within.

[. . .]

The nameless master-craftsman who breathed life, like Pygmalion of old, into the stones of the central tympanum of the West Portal at Amiens had a profound grasp of the symbolism of his subject—The Last Judgment. Certainly, his interpretation of that momentous event is clearer than that of Michael Angelo’s version as depicted in his mural painting in the Sistine Chapel. It was when I first set eyes on those inexpressibly fine sculptures—Day and Night, Evening and Dawn—at Florence, that I realised the comparative tameness of old Angelo’s mural work in the religious vein. In fact, I have a lively suspicion that the latter was merely a “pot-boiler” done at the behest of his papal patron. His Florentine sculptures are throbbing with life, and every curve and swell is arresting; while the wall-painting at Rome seems to be the effort of a man who did not believe in the theology of his subject, and had not that touch of humour which would have enabled him to satirise it.

At Amiens, on the other hand, I fancy that the unknown sculptor of the tympanum, full of the joie de viu-re, set out deliberately to poke fun at the sanctimonious “saved”; and to apply the whitewash-brush to the eternally “damned”—out of sheer fellowfeeling for the bottom dog. Observe the general poise of the several figures, the very attitude of their limbs, the sleek at-ease-in-Zion expression of the features, the prudish arrangement of the draperies of those enjoying salvation. Contrast with them the nonchalant air with which certain of the doomed step lightly along to be swallowed up in the colossal maw of the monster representing the Jaws of Hell. There is one bright-looking fellow who seems to smile to himself as he stands in the very mouth of the pit itself! These, with numerous other little quips and cranks and suggestions, go to betray the old guildsman's orientation towards the orthodoxy of his time ; and make of this sermon in stone a kind of petrified “Holy Willie’s Prayer” to those who can read between the lines of the illuminated stone manuscript of the “Bible of Amiens.”

Architecture has been cleverly defined as Frozen Music. It is not too much to say that the ancient craftsmen who composed the architectural harmony at Amiens have given the very stone a soul. Though each of the collaborating composers was able to set the seal of individuality on his own handiwork, yet the tout ensemble exhibits that unity of expression which is the hall-mark of the collective artistic teaching of that early epoch.

The glass of the great Rose-window of the South Transept is a veritable Beethoven symphony frozen into resplendent colour. To-day the sunlight streamed through the vitraux, and projected specks of colour against the masonry of the internal arcading. Pulsating with the mellowed beauty of the ages, the glass is as enthralling to-day as on that early morning when the sun first pierced its coloured glory, and cast its many-tinted reflections at the feet o£ the old monks treading their narrow way on the pavement below.

One cannot look on mediaeval glass without feeling impelled to contrast its beauty with the sickly, gnudy, crudely-coloured stuff that our modern “firms,” which pursue “art” for profit’s sake, tum out by the acre for the whited sepulchres of Churchanity in Merrie England. Those anonymous guildsmen who set their gems in the tracery of the rose-window at Amiens must surely have lived nearer to the marrow of things than do their present-day Trade-Unionist representatives who exist on the bones.

To stand within the triforium passage of the Nave, and to look down upon the pigmies of priests and populace crawling, like so many ants, across the vast floor of the cathedral, would cause the veriest clod to shudder at the thought of the glory of Amiens being at the mercy of modern warfare. As the precious manuscripts of Alexandria were devoured by the flames of the vandals in the springtime of civilisation; so may the Bible of Amiens be doomed to mutilation or even destruction at the hands of the modern apostles of “civilised“ warfare. Should a few leaves only be scorched in the heat of the present conflagration, the damage will he irreparable; and the missing pages be a perpetual reminder to future ages of the sacrilege committed during the great war of the nations. . . . .

[. . .]

On the train between Amiens and Ham I travelled with a group of British Tommies on their way back to the trenches. They were not aware, of course, of their destination, but knew that they had to change at Nesle to go up the lines “somewhere in France.” As usual in the War Zone, there were no lights in the compartments; so we sat in the darkness, jolting and jogging along at a snail’s speed. The soldiers were attempting to keep cheerful by making meagre jokes amongst one another. One worthy shouted: “Are we down-hearted?” but it was a very mild “No” that came from the poor fellows.

Another 'l'ommy who had just returned from leave in England regaled his mates with a tale of his exploits one Saturday night. His mother had asked him to make some purchases at Lipton’s, and he had found such a crowd inside the shop that he could scarcely move about. However, he managed to work his way gradually to the counter, past the tables from which he helped himself to the packets and tins displayed thereon. He stuffed his pockets with as many articles as he could cram into them, and nobody noticed him! But when he got home and emptied his pockets of the stolen prizes, he said with a laugh: “I’m damned if every bloody one of them wasn’t a dud!” Apparently the managers of Lipton ‘s know their business well enough not to place anything but dummy goods within reach of their customers in these days of food-queues.

Chapter VIII

In the Rhone Valley

7 July.—This evening my Irish friend and I strolled from Dôle to Rochefort, and sat on the cliffs there which overhang the River Doubs. It was a typically French picture that was seen from those grey cliffs in the Jura. Some 150 feet below Nôtre Dame de Consolation—the Chapel on the crown of the rocks—the placid river gingerly felt its way over the weir, which diverts the driving power to the neighbouring mill. A great expanse of land under crops lay beyond the farther bank; the distant background of pines in the great Forêt de Cliaux showed sharply against the sky. Red-roofed cots peeped out here and there in the mid-distance; crops of various kinds added another tone to the wonderful colour-scheme; poplars punctuated the landscape like tall shimmering ghosts that had wrapped their mantles closely round them; and the hush of midsummer evening seemed to bathe the whole panorama in the heaviness of sleep.

This sleepy, old-world village nestles at the foot of the chapel-hill—in the folds of its long green skirt, so to speak. Gable peeps over gable, barn over barn; clusters of vine cling to the cottage fronts; clematis and honeysuckle clamber daringly over porch and portico ; the village church tower pushes its way above the stately roundness of the chestnut trees. The ancient gate-house that guards the entrance to the hamlet, serves to remind us that its great, round archway would at one time resound with the clamour of a more boisterous generation than that which to-day passes under it.

14 July.—Paris was given over to the celebration of her National Fête to-day in commemoration of the taking of the Bastille in 1789. The monument on the Place de la Bastille was laden with the usual floral decorations; and the statue of Jeanne d’Arc, opposite the Tuileries in the Rue de Rivoli, was also literally covered with bright-coloured flowers. The national tricolour was in evidence everywhere; but there was a want of joyfulness among the people over whom still hangs the awful uncertainty of the German advance on Paris.

15 July.—“Big Bertha” again dropped her iron visiting-cards on Paris. The first shot dropped at 2 p.m., and was punctuated by the usual shrieks from the crowd in the Rue de Rivoli outside my office window. As I sat in the “Jardin du Vert Galant” in the evening, the long-range gun kept up its persistent attempts to demoralise Paris. One of the shells landed with a splash in the river itself, about 100 yards from where I sat reading, and it exploded immediately with a terrific crash, uplifting the water like a fountain, but doing no damage whatever, not even to the walls of the embankment. Those sitting on the benches under the trees rose up suddenly, and hurriedly made themselves scarce; and I was very soon left by myself in the tiny garden of the “Green Gallant.”

|

|

| Members of the Friends’ War Victims’ Relief Committee were identified by this eight-pointed red and black star. Bell mentions the emblem only toward the end of his journals on March 30, 1919. “The first sign of recognition of the red and black star of my Unit was at Golancourt, where a small boy ran out from a doorway, instantly recongised the badge on my arm and bolted back into the house, shouting excitedly, Les Amis, maman! Les Amis!" Later in that same entry, Bell writes, “an old man, recognizing my red and black star, took it to be the Star of Hope, for he came forward gleefully to ask if Les Amis had at last come back to build him another hut.” Fourth Report of the War Victims’ Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, October 1916 to September 1917, (London: Headley Brothers, 1917), cover detail. |

|

Chapter IX

In the French Alps

27 July.—On arrival at Samoëns this afternoon, I found that *rth*r B*xt*r and C*rt*s Pr*st*n and the “Spanish Flu” had preceded me at the “Bellevue Hotel,” where the F.W.V.R.C. has its Home for Repatriates. At this institution, the Mission receives sick women who have been sent back from Germany, builds up the health of those unfortunate refugees, and passes them on to their respective villages, if these are liberated. This fine work is in charge of an able American lady, who has the willing co-operation of a staff of experienced nurses and other helpers.

This sudden outbreak of “Spanish Influenza” seems to have caused an enormous amount of consternation and surprise throughout the world; but it is not at all remarkable that a “new” disease should break out during the course of Armageddon. Indeed, it would have been more unusual if the war had not resulted in an epidemic of one form or another. It will be instructive to read what the learned scientists have to say as to the origin of La Grippe, after they have pursued their studies to the end in their laboratories, and discovered, by isolating the germ, whether it is a separate organism, or only an old disease fobbed off under a fanciful name. But the utmost skill displayed in the medical colleges will not reach the source of the trouble.

I believe the worldwide antagonism that has been raging for over four years has produced a state of mind which has expressed itself ultimately in physical form upon mankind. For the world cannot go on indefinitely thinking violent and vengeful thoughts without a physiological reaction setting in at last. The pity is that the innocent will suffer as well as the guilty: that the anti-militarist who still acknowledges the supremacy of medicine for curing all the ills to which the flesh is said to be heir, will fall a prey to the new scourge, as well as the militarist. Innocence of the crime does not save the victim from the murderer; likewise innocence of the crime of war-making does not save the innocent anti-militarist from the diseases caused by war—whether ruined homes, starvation, rape, atrocity, or “Spanish Flu”—if that anti-militarist still believes in the material remedies of the Churchaniteer, and not in the spiritual immunity of the Christian.

Chapter XII

In Paris and Savoy

15 October.—The first member of the Unit to fall a victim to La Grippe passed away to-night in the person of our worthy accountant on the Paris staff, Philip Meyer. He was the gentlest of souls, a thorough master of his work, and a musician to the finger-tips; and his cheerful presence will form a sad blank in the lives of those of us who were privileged to call him our friend.

23 October —Aubyn Pumphrey passed away to-day, as a result of pneumonia following upon an attack of “Spanish Influenza,” according to the doctor who attended him. Pumphrey was one of the group who worked at Ham all last winter; and was in charge of a saw-mill at Noyon most of the time—his engineering knowledge being thus made use of. He was a tireless worker; anxious at all times to give of his best; and one of the most lovable of men. I feel that he has died at his post through sticking to it too long when he was very ill. But, like all true soldiers who fall on the field of battle, he did his duty to the very last—and “How can man die better?”

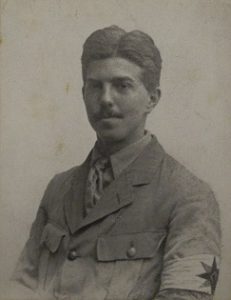

|

|

| Aubyn Harrisson Pumphrey, a fellow FWVRC member known to William Bell, died of pneumonia following influenza on October 23, 1918. Note the FWVRC star on his sleeve. According to the Botham School Archives, Pumphrey is “buried in the cemetery of St. Cloud, near Paris.” “in Memoriam: Aubyn Harrisson Pumphrey,” Botham School Archives (blog) June 20, 2019. blogs.boothamschool.com |

|

Chapter XIII

The Armistice Fete in Paris

3 December.—Tout le monde seems to have “got the wind up” about the present epidemic of Spanish influenza; and gargling is being resorted to by many people in order to stave off the trouble. It was suggested to me to-day that I ought to take the precaution of using a throat-gargle; and when I remarked that the stuff had much better be poured down the sink, as there it would have at least a chance of killing some microbes, I got a look which plainly meant: “Why, the poor man is delirious with the first symptoms of the disease already!” When I went on to declare that the malicious germs that were at the moment roosting in my larynx, were impotent because of my disbelief in material causation, that was enough to prove that my mental balance was out of gear.

It is illuminating to hear the remarks of the public at a crisis like the present in regard to disease; for the gist of them proves conclusively what an enormous amount of fear there is abroad in the world to-day. I become more certain with the passage of time and the fulness of experience that the human species passes the greater part of its waking hours in a state of fear of something or another—the fear of future want, the fear of sickness, the fear of social ostracism, the fear of accident, the fear of misunderstanding, the fear of being misunderstood, the fear of religion, the fear springing from lack of religion, the fear of God, the fear of the Devil, the fear of all the other bogies of existence, ending with the fear of death itself—the last fear that shall be overthrown.

I am intuitively convinced that there is a connection—psychic or otherwise—between this latest epidemic and the war that has been dominating the world for over four years; for both epidemics have their common source in fear. How to link up this latest expression of fear with that which underlies the war is a study from which much helpful information for the human race may be extracted. Were our professional psychologists to focus their attentions and researches in this direction, I feel certain that something worth while would be the result. But they go fumbling about on the surface of things, and never, except in rare instances, even scratch off the veneer from their subject.

Chapter XIV

In Paris

24 December.—I shall here make a note that lately I have been nursing patients suffering from La Grippe, sleeping in their bedrooms, ladling out their medicines, and doing the other little delicacies that a sick man expects. It is interesting to remember that in spite of every precaution taken against contracting the fashionable disease—by gargling the throat with antiseptics, using eucalyptus on the handkerchief, keeping away from the infected areas round patients, and the other expedients resorted to by those fearing the pandemic now raging—many individuals have been laid aside under the influence of this strange influenza. As I have not been out of the contaminated area of patients for many months past, and yet I have not resorted to any material precautions, it is impelling certain folks to enquire the reason of my escape. When I remark that I am mentally immune from the disease, they generally look as if they thought I was mentally deranged! Sometimes I say, in reply to their questions as to whether I have any theory on the subject, that I have been mentally inoculated against Spanish Influenza—a declaration which is equally mystifying to them.

T*m C*p* developed an idea that he would like to go to “Midnight Mass” at “Nôtre Dame,” this being Christmas Eve. Being a wonderfully fine evening, I thought I should like to hear the organ, if not the service; so off we set together. There was, unfortunately, no service being held at “Nôtre Dame”; so we decided to try “St. Eustache,” where we found a queue lined up at the main entrance waiting for the door to be opened.

As we stood chatting to our neighbours, an American soldier took his place at the end of the queue; and I heard him asking what the price of the seats were! I discovered, on speaking to him, that he had mistaken the church for a Cinema-Theatre! Just to hear what he would say, I asked him if he would like to come inside to hear the organ-music, and he replied: “Me! Me go to a god-dam church, son? Nothin’ doin’, boy, nothin’ doin’!” When the French people in the queue had it explained to them that the American had thought it was a Cinema-House, they rocked with laughter at his mistake.

Soon afterwards an old Frenchman passed by, and, seeing the waiting queue, he asked if we were all waiting for “Le Bon Dieu.” Not expecting an answer, he continued by telling his fellow-citizens that they would have to wait a long time before they saw “Le Bon Dieu,” and then the old infidel moved on. ![]()