print preview

print previewback EMILIA PHILLIPS

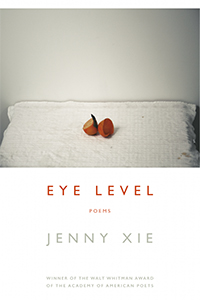

Review | Eye Level by Jenny Xie

Graywolf Press, 2018

|

In “On visibility,” art critic John Berger locates the two ways that a proverbial eye interacts with the subjects of its seeing: there’s the “eye receiving. . . . [b]ut also the eye intercepting,” a look that passively gathers visual information and a look that actively influences another’s being or behavior. This “interception” happens in one of two ways: through the gazer’s subjective transfer of visual information into meaning or through a subject’s awareness of a gaze and their subsequent modulations of behavior. “Look at how I perform for you / Look at how you perform for me,” writes Jenny Xie in her first poetry collection, Eye Level, a book that wrestles with the triangulated relationship between sight, self, and the Other. How does the presence of another’s sight influence what is (and, indeed, can be) seen? Does the traveler, in particular, warp—through their presence and gaze—a place to a degree that they can never see its “authentic” version?

The book opens with a speaker on a “sleeper train” describing the “clean slabs of rice fields” seen “[b]etween Hanoi and Sapa” in Vietnam. The speaker then recollects “a motorbike with a hog strapped to its seat” she saw earlier and how it appeared as “the size of a date pit from a distance.” This comparison of the motorbike to the date pit establishes just how fixed the poem’s—and, indeed, the book’s—point of view is: first person, subjective even when presenting as near-objective reportage, fixed in time and place with a gaze that has a direction and a phenomenological orientation, and synthesized by past experience and the sociocultural conditions of their unique life. In describing the nature of poetic imagery, Ellen Bryant Voigt writes:

Image can supply not only what the writer-as-camera uncovers in the empirical world, or what the writer-as-ecstatic isolates and articulates from the whirl of the individual psyche, but the moment when both are fused in objects seen, heard, smelled, and rendered with human response still clinging to them.

That is, an image is always a product of subjectivity, of a subjective experience of the observable world. As a poetic ethos, this idea complicates the (not entirely distinct) genres of documentary poetics and the poetry of witness, both of which seemingly aspire, as Philip Metres puts it, to “testify to the often unheard voices” either through found materials like interviews and records (e.g. C.D. Wright’s One With Others) or the gaze of an event-adjacent poet (Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel”). Some documentary poetry, I’d argue, tries to hide the poet’s subjectivity behind facts and evidence, whereas the poetry of witness deactivates the poet’s subjectivity by positioning the poet-speaker in a passive role during the events that make up the poem’s dramatic situation but in an active role in the poem’s utterance, which takes place, presumably, after the fact. With Xie, however, the speaker never cloaks her subjectivity or presumes herself a representative for all that she sees and witnesses. Thus, the book’s title underscores the vantage from which the reader experiences the world in this book—as readers, we’re at the poet’s eye level here, pressing her gaze onto our eyes like a pair of binoculars. But what lush, evocative detail those binoculars reveal!

One of the shortest poems in the book, “Alike, Yet Not Quite,” catalogs a series of images across nine lines of incomplete sentences. The poem begins:

Thin fish bones arranged on the bone plate, a bracelet

Blushing after wine and high sun

The Buddhist nun, like a tipped glass, emptying through the mouth

Smell of shadows in both March and October

A “human response” clings to each detail, vibrating with connotation and association. Someone is present to compare the Buddhist nun to a “tipped glass,” to synesthetically describe the shadows as having a smell. Likewise, there’s some ambiguity in the lines’ relationships to one another in the syntax. Is the bracelet blushing or is something else blushing? Could the smell of shadows be emptying through the mouth also? In this poem and elsewhere in the book, Xie’s image narrative—that is, the subtextual story suggested by the progression of images, after Italian writer Cesare Pavese’s immagine-racconto—constellates a story of a person in conflict, who is in attentive awe of their surroundings but also defamiliarized by them. She must make connections between these objects and experiences by connecting them to more familiar ones. Later in the poem, the “railway conductor’s face” is described as “blank as the underside of a river” and a medical gown is “onion skin.” The title introduced a conceit of a simile-esque equation; therefore, when the speaker says, “Solitude and coarse wanting,” we understand that these two emotions are “alike, yet not quite,” a phrase that could likewise describe the speaker’s understanding of the self among others.

“I’m still where I am, in conditions of low visibility,” Xie writes in “Phnom Penh Diptych: Wet Season.” The statement at once reads literally—the speaker is in Cambodia’s capital during the wet season, which causes the meteorological phenomenon of low visibility—and figuratively—the “I” is still within the vantage point of its body, and that I has “low visibility,” either to itself or to others. Xie frequently investigates the experience of the “I” alone. In “Solitude Study,” Xie writes:

Yet I know we can hold more in us than we do

because the body is without coreand when I can no longer keep dividing

the odds are in my favor to strike it out alone.

There is a reverence, even desire, for solitude, to cultivate one’s internal life by leaving familiar places and existing in unfamiliar ones without the accompaniment of another. “I developed an appetite for elsewhere,” Xie writes, and we follow the poet from Phnom Penh to New York’s Chinatown to an unidentified backyard where two bucks are “grazing the chicory.” This is a book of extensive travel—across the world and within the self concurrently. This dynamic is further underscored by the homonymic interchangeability of “eye” (the organ that allows the speaker to see unfamiliar places) and the “I” (symbol of body and mind). The eye is the “acquisitive, insatiable I” made manifest in the body.

Occasionally, the poet’s attention shifts, curious about “what eyes cannot pry open.” It seems that language (not text, the visual representation of language) is one of those things the eye cannot pry open. Language is elusive and imperfect and, thus, bewilderingly evocative to Xie. “There are no simple stories, because language forces distances,” she writes in “Invisible Relations.” Whatever is seen by the eye is transliterated into meaning by the I who in turn transliterates it into language, where there are “infinite places . . . to hide.” Despite the book’s proliferation of description, Xie writes that some details cannot be included, perhaps because there is no way to render them in language: “It’s useless to describe the slurry of humidity or the joy of a fistful of rice cradled in curry, but it’s not that I’m at a loss for words.” It’s just that the words are at a loss to contain the things they signify.

“Sight is bounded by the eyes, / making seeing a steady loss,” Xie writes elsewhere. The loss happens when one attempts to know what one sees, for knowledge is inherently incomplete. “Nothing is as far as here,” Xie writes in the collection’s final lines, suggesting that what one immediately experiences is othered—indeed, made distant—by one’s senses. By seeing, one immediately gestures toward the divide between the gazer and the subject of their sight, the self and the Other.

Whether because of its vivid imagery, sustained meditations, or deft language making, Eye Level continues to resonate well after one finishes the book and calls a reader back for a second, third, or fourth reading. For the compulsive underliner, there’s much to mark, including a plethora of aphoristic statements—like “Desire makes beggars out of each and every one of us” and “Beauty, too, can become oppressive if you let it, / but that’s only if you stay long enough”—but, make no mistake, this collection strives beyond its own conclusions, recognizing “the way I don’t know could open / months later like a hive.” Here, Xie’s eye is a globe with an irresistible gravitational pull, drawing toward it subjects of its seeing like moons that, in turn, influence the tides of attention—the poet’s and the reader’s. ![]()

Jenny Xie is the author of Eye Level (Graywolf Press, 2018), a finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry and the PEN Open Book Award, and the recipient of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets and the Holmes National Poetry Prize from Princeton University. Her chapbook, Nowhere to Arrive (Northwestern University Press, 2017) received the Drinking Gourd Prize. Her work has appeared in Poetry, New York Times Magazine, New Republic, and Tin House, among other publications, and she has been supported by fellowships and grants from Kundiman, Civitella Ranieri Foundation, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and Poets & Writers. She lives and teaches in New York City.