Sewing Bird: A Collaboration

2007 Artists and Writers Exhibition

Flippo Gallery, Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, Virginia, Spring 2007.

Curated by Katherine Shaw-Sweeney

In 2007, sculptor Carole Garmon and the late poet Claudia Emerson, inspired by two antique “sewing birds,” collaborated for the Artists and Writers Exhibition at Flippo Gallery, Randolph Macon College, in Ashland, Virginia. A sewing bird (or hemming clamp, or gripper) is a decorative clamp that screws to a tabletop and apparently dates, in the design of a metal bird, to the mid 19th century in the United States. Though examples of such tabletop sewing clamps presumably existed earlier on this continent and in Europe, the first evidence of the bird design that Blackbird could discover for the United States is 1852, with patents being filed in 1853 and 1854.

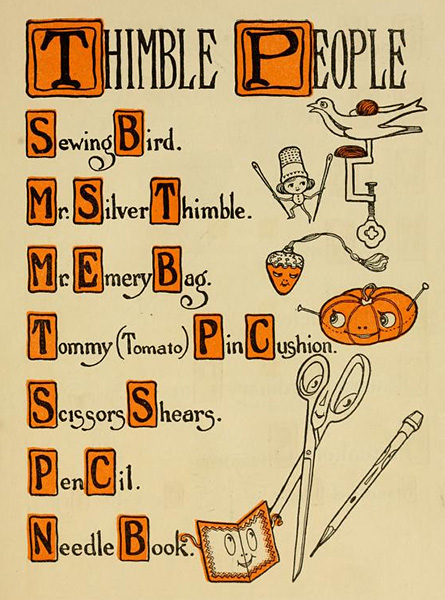

The following image from the 1913 children’s book, The Mary Frances Sewing Book; or, Adventures among the Thimble People by Jane Eayre Fryer, provides a clear image of one such device in use, screwed to a table edge with its C-clamp base. With the fabric held in the sprung beak, the sewer’s two hands are otherwise free to work with the taut cloth.

|

| Jane Eayre Fryer, “The Sewing Bird Begins to Teach,” The Mary Frances Sewing Book; or, Adventures among the Thimble People, illustrated by Jane Allen Boyer (Philadelphai, John C. Winston Co., 1913). |

By the time Fryer’s book was published in 1913, the sewing bird was already a thing of the past, a tool of another generation, replaced, for the most part, by the sewing machine.

|

| Note the sewing bird, top right, the hinge of the device visible from the beak to chest, a pincushion on its back and on top of the C-clamp. Jane Eayre Fryer, The Mary Frances Sewing Book; or, Adventures among the Thimble People, illustrated by Jane Allen Boyer (Philadelphai, John C. Winston Co., 1913). |

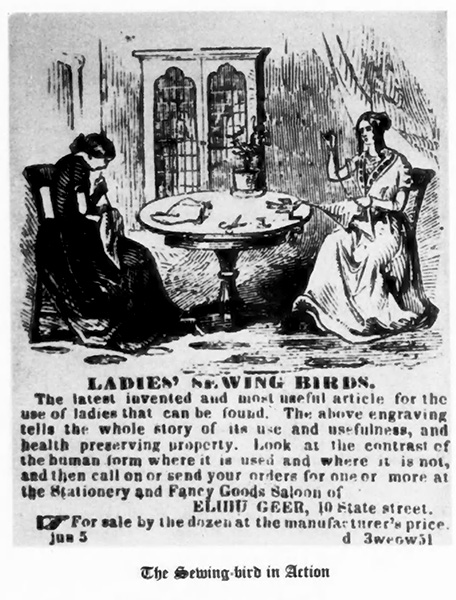

The image below is cited by several sources as “the earliest known sewing-bird advertisement” in 1852, making its selling point “the contrast of the human form” between the woman left working, bent over, with her sewing, and the woman right, with upright posture, using her sewing bird for assistance.

|

| Hartford Times, June 5, 1852 |

In, or near, the same month that this advertisement appears in the Hartford Times, the following passage appears in several periodicals, ranging from Farmer and Mechanic to Godey’s Lady Book, touting the usefulness of “the ‘Sewing Bird’ to the protection of the ladies.”

Ladies’ Sewing Birds

Our Yankeee friends are always contriving some thing useful, neat, and practical in some of the departments of social and business life. We have received from the manufacturer, C.E. Storm, of Middletown, Conn., a very convenient article, to which the inventor has given the name of “Sewing Bird.” This Bird is fastened to the table by a screw, and holds in its beak the material upon which the lady is employed with her needle. The present practice is to pin the article to the dress, which has the effect of placing the body in a stooping position, tending to round the shoulders, and to injure the lungs. The “Sewing Bird,” however obviates all the difficulties, by allowing the person to sit upright in a natural position, and to pursue her work with greater ease and facility. Believing such to be its advantages, from a neat lithograph which is now before us, we commend the “Sewing Bird” to the protection of the ladies. —Exchange.

(Farmer and Mechanic: Devoted to Mechanics, Manufactures, New Inventions, Science, Agriculture, and the Arts. Vol 10. No. 23. June 5, 1852. Also found in Godey’s Lady Book, June 1852, and Portland Inquirer, July 1852.)

|

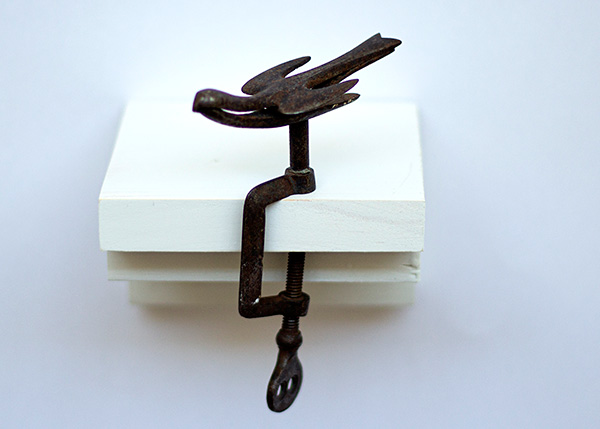

| Claudia Emerson’s Sewing Bird Photo by Kent Ippolito |

|

| Carole Garmon’s Sewing Bird Photo by Patricia Keitz |

At the center of the Sewing Bird collaboration between Garmon and Emerson was a friendship and an academic exchange for the two Mary Washington University colleagues, who also took classes from each other. With existing documentary photographs of Garmon’s visual art, Emerson’s manuscript of the poem “Sewing Bird,” as displayed adjacent to Garmon’s visual work in the gallery, and in conversation with Carole Garmon, we remember Claudia Emerson and her work through our discussion—and exploration of—this collaboration.

~

M.A. Keller: Can you tell me the story of your friendship with Claudia Emerson? You were colleagues at Mary Washington to start, right? Or did you know her before?

Carole Garmon: I think it was the summer of 1998, before I started at Mary Washington, my friend and VCU professor Camden Whitehead told me that his friend was starting at the college and that I should meet her. I introduced myself to Claudia during our orientation and told her about Camden’s urging. We enjoyed spending that week together but it went no further than that. I didn’t know at the time Claudia was going through what would become her divorce from her first husband.

It was maybe a year later that we reconnected and hit it off. She had just met Kent [Ippolito] and we would go listen to him play at local bars and we would meet up at a “special table” in the Faculty Dining Room to hold court with the good ole boys. It was a small town college Algonquin round table. Nothing was sacred—ripe jokes and raucous laughter.

One evening while my husband Kent and I were out with Kent and Claudia, I made a crazy discovery: my husband’s real name is Larry Kent and Claudia’s husband is Harry Kent! And then this: my name is Carole Ann and then there’s Claudia Ann. Her birthday is January 13 and mine January 26 (double!) we laughed and knew it was destiny.

MAK: I’ve read that you and Claudia Emerson took classes from each other at Mary Washington, an act that fostered your conversations about writing and art.

CG: We applied and were granted a Teaching Innovation Grant to take one another’s class. Neither of us had ever explored the other’s discipline. It was wonderful!

We discovered that we apply the same methods to our creative process; the only difference was master of word and material choice. We are both concerned with form, enjambment, emphasis, risk-taking, ambiguity; our lectures were identical. I must say we both did a great job and learned so much. We always meant to do a presentation regarding creative practice.

MAK: How did your collaboration for the show come about? I understand that both you, and Claudia Emerson purchased “sewing birds” each styled very differently. Was the purchase because of the show? Or did the idea for the show grow out of these purchased objects?

CG: Randolph-Macon Gallery Director, Katie Shaw, contacted us about her idea to pair artists and writers for a group exhibition. We both agreed and began the brainstorming of how we would approach this. We both have particulars when developing ideas so we agreed to focus on an inanimate object and move on from there.

We came upon these sewing birds in an antique store in downtown Fredericksburg and purchased them. So it’s hilarious—it speaks to our personalities—that she chose the Emily-Dickinson-kind-of-Victorian sewing bird, and I was like, “Yeah! I want that sleek kind of modernist approach.”

The curious woman at the counter asked why we would be so interested in sewing birds and we replied, “We’re gonna make some art!”

MAK: Were there any overt or imagined connections to ancestors who might have used such a tool? Is this something that you and Emerson talked about?

CG: We are both crazy about research; it’s one of the main gifts of being an artist. We would meet to discuss our research but that was pretty much all. We both come from pretty rural upbringings so I’m sure our ancestors would know of these.

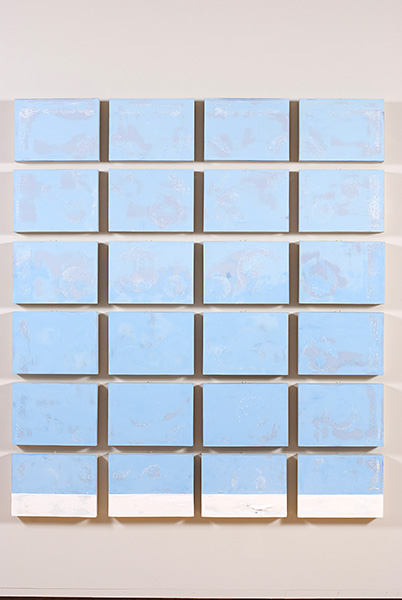

MAK: In the show, all three pieces, Emerson’s poem, your sculpture, and your painting all share the base name Sewing Bird. You have a sculptural piece that displays your actual antique sewing bird. Sewing Bird, the unraveling, and a twenty-four paneled painting, Sewing Bird (the marriage bed and “crisp sheet”). I wondered about your thinking in the rendering of “the marriage bed” broken and patterned irregularly with round doily lace on its otherwise twenty-four orderly blocks.

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet” Wood, sheet rock, paint, cast sewing bird 75 X 54 X 5 inches |

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet” (detail) |

CG: I determined the scale of my work by the size of a double bed—the marriage bed—and it happened to be close to the scale of a window in my house that I love looking out to view the events of my backyard. The “grid” presentation in my piece referred to quilting pieces (but hard and flat, yet enticing by lace snowflakes and soft color) and perhaps a window view that the bride might gaze out on while dutifully sewing.

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet” (detail) |

For some reason I settled on a winter scene, I think because I just didn’t like how these birds were meant for bridal gifts and for me meant instructional domesticity, hence a “cold” bed and the bird being trapped in the cold landscape. This strip of white snow at the bottom is the scale of the top fold of a bed sheet, I think Claudia hit on something similar as well by focusing on the “throat” of the bird. It’s funny, I think we were both cynical.

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet” (detail) |

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet” (detail) |

MAK: One of the disadvantages for our readers (and for me) is not being able to see this displayed in the gallery where we can see the textures and materials more closely. The bird “trapped in the cold landscape” as you say, a cast plastic sewing bird encased in plaster, is something that would be more clearly seen in person, but is almost lost without a detail closeup (as above) of the documenting photographs.

CG: I have always been one to disguise details and embrace nuance. I’m not one for in-your-face work. As Sally Mann says, “if it doesn’t have ambiguity why bother?”

MAK: The round doily patterns in the marriage bed panels are also on the wall in Sewing Bird (the unraveling), which contains your actual antique sewing bird. Is “doily” the right term here? What would you call this patterning on the wall that is faintly visible in the photograph? Lace?

|

| Carole Garmon Sewing Bird, the unraveling Antique sewing bird, drawing, and thread 24 X 12 X 4 inches “the elevated bird unravels its task” |

CG: I call this a kind of lace or tatting. (I was thinking more like traces of thoughts, memories, who knows?—just how I think.) And so the bird is kind of unraveling all of that. It’s a reaction—not necessarily a feminist reaction—to the gifting of the bird from a fiance to the betrothed. but you know, as Claudia talks about the bird’s closed throat in her poem, my work is talking about unraveling that notion of sitting there and doing this kind of domestic tatting.

MAK: I saw an image of Sewing Bird (the unraveling) before I had the title. I misread it as an act of making, perhaps spinning fiber from raw material; I understand now that you pose the bird as an agent of unraveling.

The bird, with your intent, or in my initial misreading, is, in both cases, an active agent rather than a passive one. The conditional passivity—and the closed throat of the sewing bird (as you’ve mentioned)—is central to Emerson’s poem, as well as some earlier sewing bird poems I discovered from the mid 19th through the early 20th century.

Understanding your bird to be unraveling the material, I also can’t help but think sideways of Penelope, unraveling the work of the day, to avoid finishing her task and to escape her suitors; the unmaking of her craft keeps her in control of an outcome.

CG: Oh yes, certainly! My bird is active but only in a limited sense; she can only move to the “lower level” to perch with the “mess” she has made. I like that.

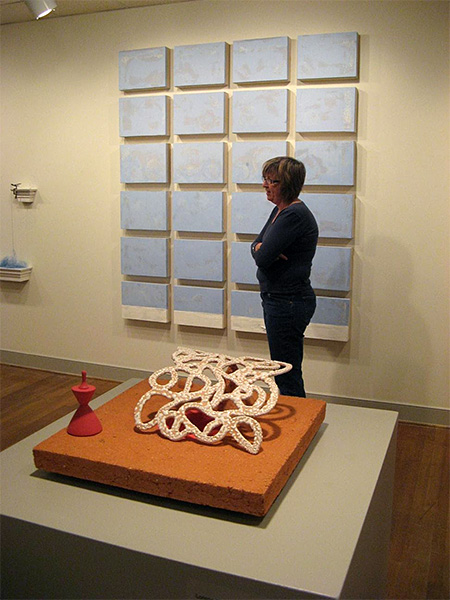

MAK: In this photograph of you in the gallery, we see the adjacency of your two pieces. Where was Emerson’s hand-written poem “Sewing Bird” mounted in relation?

CG: This image is taken from a UMW Studio Art Faculty exhibition. Claudia’s poem was to the left in our collaboration at Flippo Gallery.

|

| Carol Garmon standing in front of Sewing Bird, the marriage bed and “crisp sheet.” Sewing Bird, the unraveling is to the left. Not pictured further left is Claudia Emerson’s handwritten poem “Sewing Bird.” 2007 Artists and Writers Exhibition Flippo Gallery, Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, Virginia, Spring 2007. |

MAK: Did either of you see each other’s work in process before the show? If so, how did your feedback to each other influence the outcomes? I’m thinking of how you talked about the difference in your sensibilities in terms of which birds you picked, and how those differences might come into play in collaboration.

CG: We decided that we wouldn’t see the work in process on a regular basis because we didn’t want to make work in response to one another; we wanted to respond to the object, the sewing bird. However, I think the number of similarities in our lived experiences, and our approach to the creative process, brought forth work that examined similar themes.

|

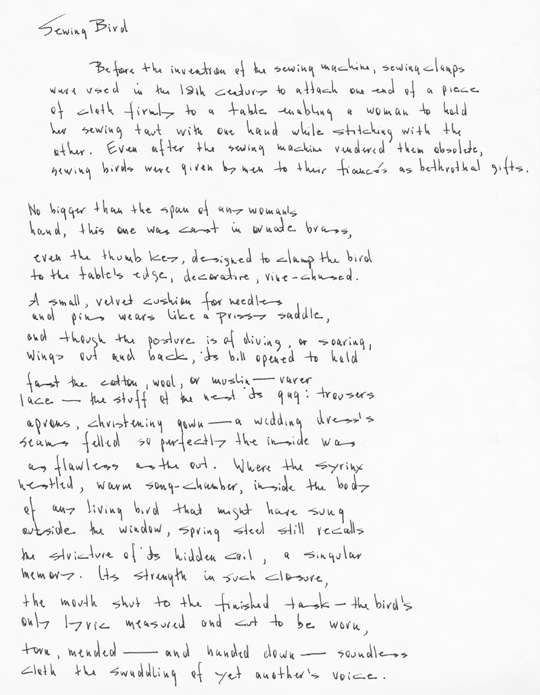

| “Sewing Bird” Claudia Emerson Handwritten manuscript |

MAK: Did you have an opportunity to collaborate with Claudia Emerson on any other projects?

CG: We only collaborated on this exhibition. Although we always discussed each other’s work. I think we both workshop/edit our work through deep delving into the creative process. The work tells you when it is done. If it ever is?

MAK: Carole, I want to thank you for talking to Blackbird about the Sewing Bird project; it was the topic of the first conversation I ever had with Claudia Emerson and I can still picture her sitting in the Virginia Commonealth University computer class room where we make the journal, describing to me a sewing bird, and gesturing toward how it clamps to the edge of a table, how it holds the fabric in its beak.

Only recently did I see her sewing bird when the journal received photos from Kent Ippolito, though Blackbird editor Mary Flinn, on hearing me tell the story of that conversation, not long ago gifted a sewing bird to me. (I love that mine has the modern lines of your sewing bird, but also the “prissy saddle” of Emerson’s.)

|

| M.A. Keller’s sewing bird—a gift from Mary Flinn. Photo by M.A. Keller |

MAK: Carole, it has been a pleasure to talk to you; we have only met only in passing before, at Claudia Emerson’s memorial event at Grace Street Theater, and at another reading or two after her death—perhaps at Reynolds Gallery? I just can’t remember everything.

CG: I hear you. But you know? Unfortunately, I do remember everything. Claudia is stuck in my head.

When she was dying, she told me, “Carole I’m not going to get old with you.”

And I said “Yes you are. Yes you are, because you’re going to be with me all the time.”

You know, Michael, you asked me if there are any photos of the two of us? I can only remember one where we were at the UMW Staff Appreciation Picnic on a hot and humid May afternoon. I don’t even know where it is now; however, I think it is perfect. We were dancing.

|

| Claudia Emerson’s Sewing Bird Photo by Kent Ippolito |

![]()

Contributor’s Notes: Claudia Emerson

Contributor’s Notes: Carole Garmon