Eleanor Rufty: The Moment Between Moments

I am indebted to the language of cinema for ways of visualizing scenes as well as certain stage-like devices in early narrative painting. In my work the poses and gestures are subtle; action is minimal. Nothing dramatic is happening. My interest lies in the moment between moments, in the sense of suspended time.

—Eleanor Rufty, artist statement, 2020.

Walking into the recent exhibition of new works by Eleanor Rufty at Charlottesville’s Quirk Gallery, I was struck first by the sheer number of charcoals, pastels, and paintings on view, and then by their color and luminosity in the generous daylight that floods that spacious new gallery. The show was curated and expertly laid out by the gallery’s director Adam Dorland. Most of the twenty-one works on view, I discovered, were completed during the lock-down months of Covid 2020. While the events of the past year pressed the air out of so many of our dreams, Rufty kept painting day by day. Out of isolation and solitude, her will to bear witness to the pulse of human connection feels tested and sharpened in these works.

|

| Eleanor Rufty: New and Selected Work Quirk Gallery, Charlottesville Virginia December 10, 2020–January 24, 2021. Photo by Amanda Gough. |

Rufty’s work earns pride of place in what has been called figurative abstraction: she is engaged with the time-honored practice of depicting the human figure in space, but she also confronts essential definitions of picture-making in her manipulation of field, frame, color, and the boundaries of the medium. Point of view, especially in her use of diptychs and triptychs, is a through-line in her work, and she has translated film’s conventions of close-up, zoom, and cut, into pictorial devices to represent time, as well as space, in her compositions. The picture plane itself becomes a thing to be cut and spliced. She must be counted among innovative visual artists who have taken cues from film, each in their own way. She also shares affinities with graphic novelists and comics artists, less for story-telling than for the challenge to expand her drawing vocabulary. Above all, her method of working incorporates an improvisational temper that runs like a motherlode through art, music, dance, theater, and cinema of the past century. Insisting on the primacy of making it up on the spot, acting in the here-and-now, she does not work from models or from photographs. She does not make preparatory sketches. She begins a work without any specific plan. She conjures composition and figure entirely from her mind’s eye. Yes, she works from life, but from the life within her. Oil paint and wax on panel, or charcoal and pastel on paper, make their own demands the moment she picks up brush or stick, and she pays attention. Every work is a dance between mind, eye, hand, and matter.

|

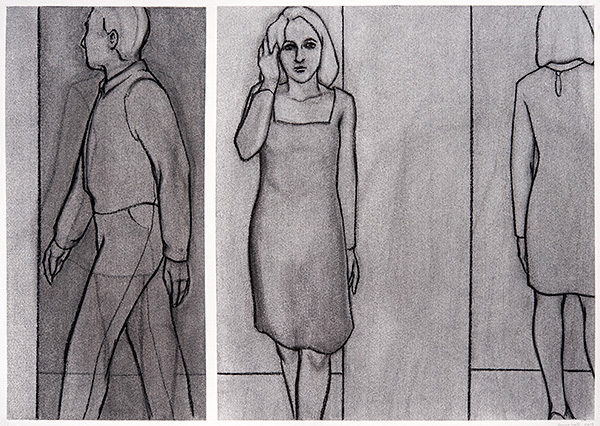

| Eleanor Rufty Exit Lines (2) 2014 charcoal on paper 29.5 x 41 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

How does she do it? She simply begins. Drawing—as in drawing water from a well—is her born impulse; hand over hand she pulls forms into view from unfigured depths. Mark by mark, fragments from what she calls her “subliminal vocabulary” appear and begin to coalesce, like chromosome fragments. As she works, a line comes to represent something, perhaps the curve of a shoulder, or a distant silhouette. It is a process of evolution.

An evolution within each drawing, and an evolution from one drawing to the next, from a deep and lifelong wellspring: at eighty-four, her attention to the human form in art and in life runs through her every nerve. Like an improvisational dancer or musician, once she has a few measures in play she can start to tease out correspondences and relations, ad-lib steps, glimpse forms. Subjects take shape, and begin signaling. What are they saying? To find out, draw more. Accidents happen, some are claimed, adjustments follow. The sheer self-imposed flux of this process is bracing to contemplate. A less bold explorer would lose the way. The viewer watches a thing come into being out of thin air.

In Rufty’s case, the stages of a picture’s coming-to-be remain visible. New lines only half-eclipse older ones as she searches a curve. Erasures halt before they occlude. Opening gambits still glimmer under translucent paint. Later, a hand moves closer to a face, legs cross, a head tilts, but outlines of their prior positions remain visible and record Rufty’s decisions. Location lines change too: horizons, floor-wall edges in perspective, framing shifts, the boundaries of the drawing on its paper: all are movable parts. Such traces imbue the pictures with an overwhelming sense of time: the tracks in real time of changes under the artist’s hand, and the accumulating choreography of a pose caught in represented time, like a time-lapse photograph by Étienne-Jules Marey.

|

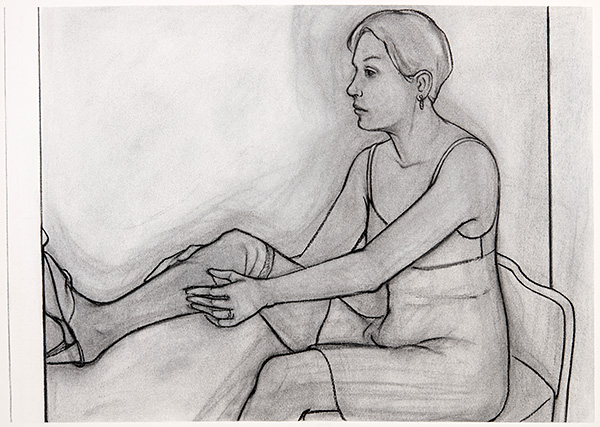

| Eleanor Rufty . . . half dressed before the mirror of her dressing table . . . 2020 charcoal on paper 29.5 x 41 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

A look at the drawing titled . . . half dressed before the mirror of her dressing table . . . (2020) shows ghost tracks everywhere. The pleasure they give the viewer is not unlike watching a soccer player, say, navigate the field. The final bold lines—hand, knee, belly, neck—resolve the pose as triumphantly as a shot on goal. She nails it! And exactly at that moment the whisper traces play a new role, arcing and pulsing at the body’s contour, giving the pose its drama and motion in a seconds-before and seconds-after timescape. Rufty works from an innate, proprioceptive understanding of the moving body, and she brings the viewer with her. Looking on, we piece together the image too, out of the multitude of proffered lines, and feel the internal origins of the form rise in our own bones. And we judge it true. The pulling on of the stocking, both legs lightly braced, the fingers of the left hand pulling and pressing, torso slightly forward: the artist recedes and the figure gains its own momentum. Including, in this drawing, the curious incident of the foot pressing against one vertical edge of the drawing itself, as if to give the frame a little push. A second vertical just beyond that left edge, proper to the drawing on its sheet of paper, destabilizes the first, as if we might glimpse the title’s dressing table in the last split-second of a film wipe.

But there is yet more to this drawing. The woman we see is not looking at what she is doing. She gazes at something else. Perhaps at herself in the mirror we can’t see, or perhaps into her thoughts. It could be an actress’s gaze, in character. The head and neck carry the weight of a mind.

The gaze in Rufty’s works is a subject unto itself. Walk through the show, and you encounter a congregation of witnesses. Figures’ sightlines fix on things outside the picture, and you instinctively imagine what is there. In groups, people look at one another or look away. One member of a couple misses the other’s glance. A dancer judges another dancer. Two women sit at a table, one listens with her eyes. Nearby, a boy searches TV channels with a remote (Jean’s Piano, 2017–18). A young man looks past us into the future (Turning Point, 2012–13). A woman, in reverie, looks out to sea (. . . I heard the sea sound sing. Elegy for Jan, 2014). Rare figures look straight at you (The Rehearsal, 2020).

|

| Eleanor Rufty Jean’s Piano 2017–18 oil and wax medium on canvas 25 x 36 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Turning Point 2012–2013 oil and wax medium on panel 18 x 18 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty . . . I heard the sea sound sing. (Elegy for Jan) 2014 oil and wax medium on panel 22 x 23 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

Look again at Jean’s Piano. At least seven figures appear in this painting, each with an active sight line. Following them, your own eye ricochets through the three receding rooms of the house like a pin ball. Rufty is famous for this (as well as for depicting other paintings within her paintings). She shows us the act of looking, the kinds of looking, in image after image, to craft an anatomy of human attention. Eyelids, irises, eyes downcast, upturned, sidelong—but gaze is further indicated by the turning and tilting of heads, in the gestures of hands, limbs, and bodies. All advance and make legible the nature of the act of looking. We even comprehend the gaze of a figure whose back is to us, from body language alone.

A visit to Rufty’s website, eleanorrufty.com, reveals works from across her career: people looking out windows, down hallways, at each other, but most often people looking—with the mind. The artist looks, from within, at looking. Could she so convince us we are seeing this kind of moment in human mental life if she was not engaged in it herself in the very act of drawing?

And what else might get carried into the picture via this improvised inside-out process of Rufty’s, as she reconstructs the body and its postures, its relations to other bodies, its states of mind? The greatest achievement of all, for any artist who renders the human form, is the capture of a representation of conscious awareness. This is what we wait in line to see at the Louvre. It is what Piero della Francesca gave us, or Antonello da Messina in his intimate Virgin Annunciate in Palermo. As if the figure in the picture sees the world going around. Or the world to come. This is the source of the quiet grandeur in this work. Rufty takes “point of view” back into the deep mystery of the mind.

~

The history of cinema is a history of the eye. As Walter Murch asked in his famous little book In the Blink of an Eye, why were spectators so instantly at home with the medium of film when it was new? His answer: because film behaves like thought itself, jumping and zooming, leaping forward and backward in time as well as space. A cut, he says, should be akin to a blink. And a blink impels a saccade, a sight-line shift. Rufty’s figures seem caught in the moment between blinks. A micro-expression, pinned down like a butterfly for us to examine, taking our sweet time!

I asked Rufty about her early influences from film, and she wrote:

I was very influenced by black and white film, specifically film noir, having grown up with it—and then rediscovering the films when they started to appear on late night TV and later on videotape. When I was making the early charcoal drawings around 1980, I did a lot of gestural drawing watching these films on TV. I began to see them more completely. The lighting is so great, especially the interiors, windows, blowing curtains, venetian blinds, lots of shadows. I started thinking about camera angles as point of view, the play between the close-up and the figure in the background, the way a figure is cut by the edge of the screen, the concept of voice-over, the suggestion of something happening beyond your view. The best of these films are formally beautiful. Since I was drawing without any other reference, this “cinematic language” gave me a way to think about forming images. (Eleanor Rufty, email message to author, January 23, 2021)

|

| Eleanor Rufty Exit Lines (1) 2014 charcoal on paper 29.5 x 41 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

Rufty touches our common nerve, in part, via a shared lexicon of film and its narrative technology. Perhaps because her “moments between moments” are so open-ended, stories crowd your mind as you study the quiet figures in her charcoal and pastel drawings. You can be unaccountably overtaken by emotion. You unconsciously mirror the pose yourself, and it reverse-sparks a moment from your life. But the pose, assembled on paper through Rufty’s restless hand, must bear stowaway signals from her own somatic memory. One glimpses autobiographical references throughout her work: portraits of herself, her family, close friends, places she’s known, though she seldom names them. It is the preternatural quality of her attention that kindles in us such specific and immediate narrative responses of our own. The writer Wesley Gibson, in an essay for Rufty’s 1997 show Voice-Over at 1708 Gallery in Richmond, marveled that whenever he talked with people about her work, they insisted they knew what the work was “about.” He thought, “Really? I was never so sure; and I was almost certain that I wasn’t meant to be so sure.” The work summoned instead, he wrote, the flattened space of early Renaissance painting, the framing devices of Matisse, and the history of formal abstraction. “But Rufty’s figures, at once iconic and specific in their rendering, do carry enormous suggestions of rich interior lives.”

The fact that we eagerly propose our personal interpretations of her pictures is the measure of just how subtly she has conjoined the iconic and the specific in her work. Putting these two near-mutually exclusive terms together, Gibson gives us as good a definition of picture charisma as we could ask, in saluting her accomplishment.

~

The paintings in the show deepen and extend the suspense of the drawings, adding color, light, liquid, and all the news paint brings. Tacit framing lines in the drawings have bloomed into fully furnished and windowed interiors, watery seascapes, and in two of the most powerful works in the show, a theater stage and a detailed artist’s studio. Place and time are more fully developed, space takes on character, and in her most recent paintings, Rufty has permitted moments and individuals from her life to step fully from the shadows.

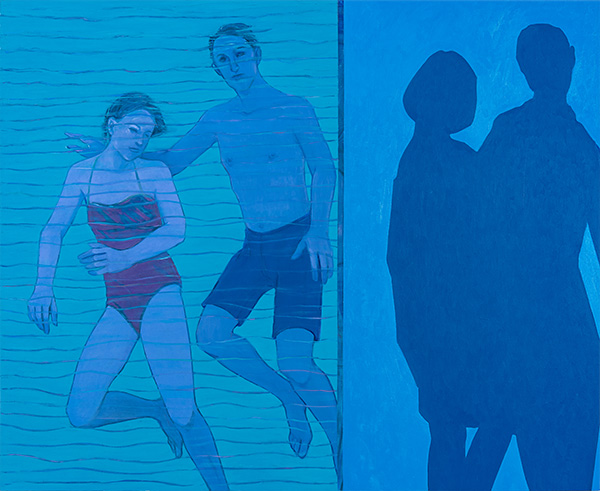

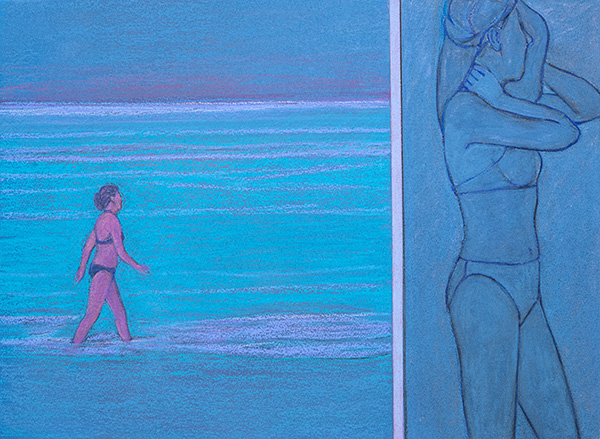

She paints in oil and wax, the wax giving the colors enough translucence to keep her signature tracks in view. Line retains its authority in the paintings, but now it delineates the figure in a nonstop contest with paint, back and forth—the paint attenuating a line’s width and weight to produce a flashing and winking glitter at the boundary of every form. The graphic capture of a body in space is all the more charged with motion and arrest. With the liquidity of paint come depictions of water itself, and she gives us figures at the shore, in the water, and under water, submerged and released from gravity (the haunting Duet, 2015 revised in 2020). She returns again and again to depictions of water. Even in her pastels she’s employed counterintuitive applications of water to gain color saturation, as seen in her Dream — Blue — Sea and Sea Window both 2011. She began this technique long ago, using pastel on heavy watercolor paper. Her series The Beach Pictures done between 2007 and 2010, show its chromatic tides, bathed in sea light, as in . . . by a faint light streaming from 2009. Her very palette is water-blue, and the prevailing tones in this show are a thousand blues. Blue pulls you in, as Josef Albers taught us. Rufty uses it to sound our depth.

|

| Eleanor Rufty Duet 2015 (revised 2020) oil and wax medium on panel 39.25 x 48 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Dream — Blue — Sea 2011 pastel on tinted paper 22 x 30 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Sea Window 2011 pastel on tinted paper 22 x 30 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty The Beach Pictures: . . . by a faint light streaming. 2009 pastel on tinted watercolor paper 29.5 x 41 inches Photo by Travis Fullerton |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Solitaire 2020 oil and wax medium on canvas 18 x 25 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

But she lays all her cards on the table in the two most recent paintings, the largest panels in the show, The Rehearsal (mounted between two charcoal drawings as pictured below) and The Blue Studio (to W. G.), both finished in 2020.

|

| Eleanor Rufty Installation shot detail Rehearsal: Trio, The Rehearsal, and Rehearsal: Duets Quirk Gallery, Charlottesville, Virginia December 10, 2020–January 24, 2021. Photo by Tim Bowring |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Rehearsal: Trio 2020 charcoal on paper 22 x 30 inches Photo by Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty Rehearsal: Duets 2020 charcoal on paper 22 x 30 inches Photo Terry Brown |

|

| Eleanor Rufty The Rehearsal 2020 oil and wax medium on canvas 36 x 46 inches Photo Terry Brown |

The Rehearsal is the most luminous painting in the show. Flanked by charcoal drawings of costumed dancers, it exerts an irresistible pull from the moment you enter the gallery. In a panorama of skin tones alight in a blue arena, fourteen figures are caught in spotlight on and before a stage, where we view a revelatory mix of performance deliberations in mid-act pause. It is a dance stage, with a sprung floor under glossy black marley that reflects their bodies in glints and echoes. We look on from an imaginary height, as if we were a camera suspended above front row seats. Behind us must be the darkened hall of the empty house. Dancers in scruffy studio garb map out the stage floor, arranged singly and in groups, some practicing, some talking, some waiting, all looking, in a crisscross web of implied sight-lines. A stage manager (or composer? set designer?) sits on the edge of the stage with a clipboard, feet dangling, in conversation with an associate, perhaps another performer. Nearby, two women stand before the stage, taking in the action from the pit. Their backs to us, they close the magic circle. All the players orbit three detailed figures at center right. A male dancer observes a costume designer testing the drape of a tunic on a female dancer. The costume designer looks straight at us out of the world of the painting, breaking the fourth wall. As if to confirm this rupture and signal the stage lights behind us, the shadows of these figures are thrown on the rear panel of the stage in a hovering parade of doubles. Adept at intimate settings and modest occupancy, Rufty in this work stages a full-on ensemble. It’s all here: stage, choreography, costume, setting, lights, dancers, crew, audience, action.

Each group in this painting, and the groups together, bear the hallmark relational charge that Rufty has perfected across her work. A subtle construction of poses, gazes, and moments is now deployed at scale to describe an epic event. The male dancer at center, hand poised, is a study in banked energy. His feet carry the weight of a mind. The female dancer suspends a turn, feet to the left, gaze to the right. The costume designer tilts his head, envisioning how the garment will look in motion to an audience: calculating their view in his mind’s eye. (A friend who saw the painting suggests that the designer is looking at a rehearsal assistant high in the steeply raked theater, and the dancers have just finished a run-through.) The moment between moments. And—because many of these figures are people that Rufty knows—these are portraits, redolent with character and idiosyncrasy. Specific. Rufty herself has designed costumes for dance over her long career, and for some of the very dancers figured in this painting. She knows a thing or two about clothes on bodies. Perhaps she shows herself here too, looking on with a friend. The friend’s hand rests on a book, one of the few objects in view. Best of all, Rufty’s innate improvisational mode here becomes the direct subject of a picture. She is choreographing a moment in the making of a dance, on a stage, in a painting.

~

|

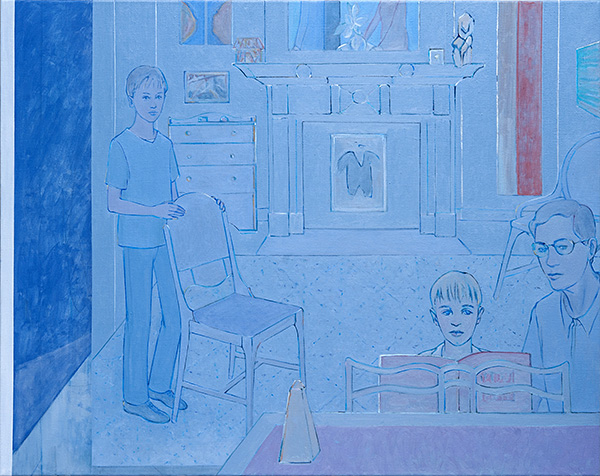

| Eleanor Rufty The Blue Studio (to W. G.) 2019–2020 oil and wax medium on canvas 38 x 46 inches Photo Terry Brown |

Rufty is unmistakably present in another of her new works, The Blue Studio (to W. G.), 2019–2020. Again with her gift for the long gaze, she paints herself, in her studio, standing with a visitor. Behind them on the wall she depicts her own painting The Music Lesson, shown as a work in progress. (That painting, finished in 2016, is also on view in this show, and hangs behind us as we turn to look at its iteration in The Blue Studio.) At her elbow are her tables laden with cans of stacked brushes, tubes of paint, her glass palette, drawings pinned all around, other works in progress, a canvas on the floor at left. She paints the tools and stuff of her craft, in a richly detailed survey of her world: a brush to paint brushes, paint to paint paint. Strips of tape are stuck to the walls, her devices for masking and interrupting perspectives. Two drafting triangles share a nail on the wall, a painterly duet of overlapping and reflecting transparencies. She rests her hand on a chair just visible in the foreground, and brings us into the picture this way. Her visitor has just turned to speak, gazing straight out of the painting, his lifted hand referencing the canvas. She is listening. We see her face in three-quarters rear profile. Her head and neck carry the weight of the listening. She paints herself listening back through time, to hear through the roar of time’s passing, her visitor’s words. He is a writer. We listen with and through her. And in his face, his gaze, the tilt of his head, and his gesturing hand, Rufty paints her reach for the voice of a friend, the writer Wesley Gibson, who passed away in 2016. Gibson, who wrote of her work that he was sure he wasn’t meant to be so sure. It is hard to know whose sorrow it is in his face, his or hers. Or ours. Over her head, a boy learns to play the piano. Over his, a brother-witness. Only a painting could orchestrate all this. The feeling of it stays with you for a long time after you’ve left the show.

|

| Eleanor Rufty The Music Lesson 2016 oil and wax medium on canvas 38 x 48 inches Photo Terry Brown |

The moments—whole lifetimes—between moments. At the close of a desolate year in our public life, the work of this deeply respected artist shines a light on our collective humanity. How hungry we are just to look at each other! ![]()

Contributor’s Notes: Elizabeth King

Contributor’s Notes: Eleanor Rufty