print preview

print previewback TY PHELPS

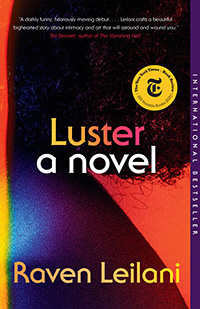

Review | Luster by Raven Leilani

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020

|

Raven Leilani’s debut novel, Luster, opens with a bang: “The first time we have sex, we are both fully clothed, at our desks during working hours, bathed in blue computer light.” In less expert hands, this opening sentence could come across as cheap, sensationalized, mere titillation. In Leilani’s hands, the line does capable work. It establishes the main relationship and hints at the bevy of transgressions to come. It gives us a clear element of time and place (offices, modern life abuzz with computers), and it establishes, crucially, that to our narrator and protagonist, Edie, this digital dalliance counts as sex. It counts as intimacy. A “private world” she and Eric, her lover, have “tenderly . . . built.”

Edie is a young Black woman and struggling artist working a low-level job in publishing. Eric, her lover, is an older, white man of some wealth. Their relationship forms the center of the novel and provides the guiding arc of the plot. Eric is married. He and his wife, Rebecca, have a Black adopted daughter. This is the situation Leilani develops from the outset, power dynamics and ever-shifting desires crisscrossing all these demographic realities, propelled by Leilani’s dense and propulsive writing style.

Edie and Eric soon graduate to in-person dates. Their first, to Edie’s surprise and discomfort, is at Six Flags, a literal and figurative roller coaster.

Leilani is careful not to make the play of these power vectors simple. Edie may be younger, be poorer, and belong to more traditionally marginalized groups, but she is both strongly desired by Eric and full of her own agency. “By the time we set our first real date,” at the aforementioned Six Flags, Edie “would’ve done anything.” Her hunger for Eric keeps him off balance, and his age and status entice her even as she is aware of the inherent imbalance in their stations.

The age discrepancy doesn’t bother me. Beyond the fact of older men having more stable finances and a different understanding of the clitoris, there is the potent drug of a keen power imbalance. Of being caught in the excruciating limbo between their disinterest and expertise. Their panic at the world’s growing indifference. Their rage and adult failure, funneled into the reduction of your body into gleaming, elastic parts.

As they scale up a roller coaster, Edie again demonstrates the complexity of her desire: “All I want is for him to have what he wants. I want to be uncomplicated and undemanding. I want no friction between his fantasy and the person I actually am. I want all of that and I want none of it.” By the time they return home and they begin to kiss in Eric’s car, the longing has become a torrent. Eric asks Edie to suck his fingers and calls her a “fucking slut.” Edie immediately invites him upstairs, an invitation which he declines.

The violence percolating in their sexual behavior escalates as Edie longs for sex that Eric, through several more dates, withholds. They shove each other in a bathroom. Edie later says she’d like for him to do it again, which Eric finds deeply uncomfortable. When they do finally have sex, on page forty, at Eric’s house while his family is out of town, both are so desperate and uncertain and raw that the enormity of all existence rises out of the details embedded within Leilani’s volcanic sentences:

. . . I feel panicked all of a sudden to have not used a condom and I’m looking around the room and there is a bathroom attached, and in the bathroom are what look to be extra towels and that makes me so emotional that he pauses and in one instant a concerned host rises out of his violent sexual mania, slowing the proceedings into the dangerous territory of eye contact and lips and tongue where mistakes get made and you forget that everything eventually dies, so it is not my fault that during this juncture I call him daddy and it is definitely not my fault that this gets him off so swiftly that he says he loves me and we are collapsing back in satiation and horror, not speaking until he gets me a car home and says take care of yourself like, please go . . .

In the sort of dazzling and surprising turn that Luster pulls off time after time, Edie, ten days later but in the very next paragraph, winds up visiting Eric’s house while she thinks no one is there. As she fondles the clothes in Eric’s wife’s closet, Rebecca enters. Edie’s willingness to transgress boundaries continually gets her in trouble, and yet she remains both compelling and sympathetic as a character.

Edie eventually returns to the house after losing her job in publishing. Again defying reader expectation, Rebecca offers Edie a place to stay, and they form a strange, uneasy alliance, while Edie also forms a tense, complicated, almost-mentorship with Akila, the adopted daughter.

The novel is not perfect, though Leilani covers the few flaws in the book with her ample strengths. The middle spins its wheels a bit, for instance, though Leilani keeps the reader engaged through the sheer velocity of her prose and the relentless pace of Edie’s interior narrative combined with the chaos of modern New York. The reader eventually emerges, breathless, for the novel’s climatic set-piece.

Ultimately, the success of this novel comes down to the depth of Edie. Though it rests on the foundation of Edie and Eric’s relationship, the novel explores the full gamut of Edie’s experience: beyond the modern romance, complete with dating apps, open marriages, and sex that bristles with hunger and violence, Luster is a workplace drama and a family history. Edie is a painter who struggles to put the truth into her work, and the book is thus also a documentation of artistic growth and discovery. It has been called a “Millennial novel,” and in some ways it is, as Edie narrates and navigates the big city on a less-than-shoestring budget, searching for ever-elusive satisfaction.

We talk a lot in the writing community about characters being fully formed human beings, about them being three-dimensional. We say things like “round” characters versus “flat” characters, we talk about flaws and foibles, about characters surprising us as they begin to live their lives on the page. Yet these terms are all inadequate in describing the magic of fiction at its very best, the magic of Le Guin, of Baldwin, of Paley, and now, too, the magic of Leilani.

Vonnegut allegedly said that “every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” And what this reviewer loves about Edie, what feels so real about Edie, is that she may want a glass of water, sure, but if she does, it seems that she wants it both sparkling and still. She wants it in a wine glass and Nalgene bottle and that Captain Planet mug that recurs so often in the novel. She wants to swallow it and hold it in her mouth and rinse her face and spit it out like a fountain. To dump it on Eric’s head and use it to bathe him. She may want to swim in it like an ocean, away from everything, and perhaps take Akila with her. I imagine her using the water to mix her paints. A glass of water, sure, but also an ever-forking river, raging rapids and quiet pools, running like veins through, as Leilani writes, “everything that wants to live” and through that part of Edie “that is ready to die.”

Edie holds all this enormous longing, believably, within her character, thinking of the “hours when I am desperate, when I am ravenous, when I know how a star becomes a void.”

So often characters in fiction want what they want with a singular focus. They may be distracted along the way, but they continue to struggle toward some fixed goal. And maybe this is indeed how some human beings in the world experience desire. But Edie’s constant fluctuation, her big, earnest, complicated mess of feeling and longing and need, this “composite of contradictory shadows,” as Edie describes her painting of Rebecca in the novel’s final pages, seems much closer to the truth of our shared human experience.

Edie shows us this truth, and what a gift it is to read it. ![]()

Contributor’s notes: Ty Phelps

Contributor’s notes: Raven Leilani