print preview

print previewback KAREL ČAPEK

R.U.R.

Description of Characters

DOMIN : A handsome man of 35. Forceful, efficient and humorous at times.

SULLA: A pathetic figure. Young, pretty and attractive.

MARIUS : A young Robot, superior to the general run of his kind. Dressed

in modern clothes.

HELENA GLORY : A vital, sympathetic, handsome girl of 21.

DR. GALL : A tall, distinguished scientist of 50.

MR. FABRY : A forceful, competent engineer of 40.

HALLEMEIER: An impressive man of 40. Bald head and beard.

ALQUIST: A stout, kindly old man of 60.

NANA: A tall, acidulous woman of 40.

RADIUS: A tall, forceful Robot.

HELENA : A radiant young woman of 20.

PRIMUS : A good-looking young Robot.All the Robots wear expressionless faces and move with absolute mechanical precision, with the exception of SULLA, HELENA and PRIMUS, who convey a touch of humanity.

~

ACT ONE

SCENE: Central office of the factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots.

|

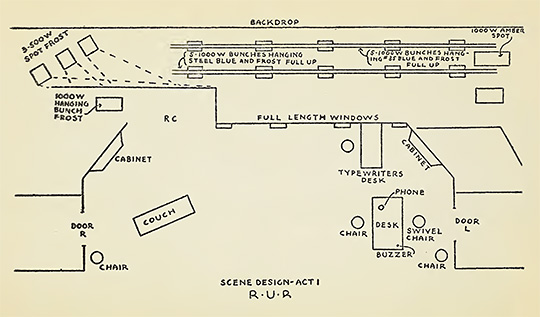

| Scene Design Act 1: R.U.R. |

Entrance R. down Right. The windows on the back wall look out on the endless roads of factory buildings. Door L. down Left. On the Left wall large maps showing steamship and railroad routes. On the Right wall are fastened printed placards. (“Robots cheapest Labor,” etc.) In contrast to these wall fittings, the floor is covered with splendid Turkish carpet, a couch R.C. A book shelf containing bottles of wine and spirits, instead of books. DOMIN is sitting at his desk at Left, dictating. SULLA is at the typewriter upstage against the wall. There is a leather couch with arms Right Center. At the extreme Right an armchair. At extreme Left a chair. There is also a chair in front of DOMIN’S desk. Two green cabinets across the upstage corners of the room complete the furniture. DOMIN’S desk is placed up and down stage facing Right. Seen through the windows which run to the heights of the room are rows of factory chimneys, telegraph poles and wires. There is a general passageway or hallway upstage at the Right Center which leads to the warehouse. The ROBOTS are brought into the office through this entrance.

|

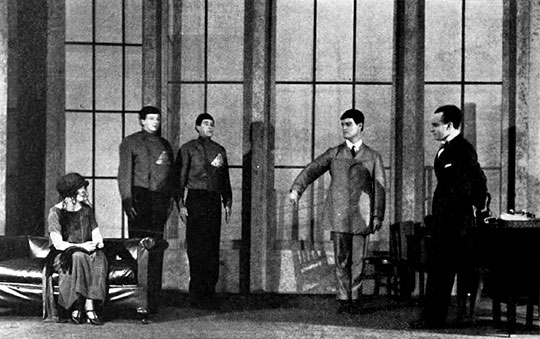

| R.U.R., Act I Garrick Theatre, New York, Theatre Guild Production 1922 |

DOMIN (Dictating)

Ready?

SULLA

Yes.

DOMIN

To E. M. McVicker & Co., Southampton, England. “We undertake no guarantee for goods damaged in transit. As soon as the consignment was taken on board we drew your captain’s attention to the fact that the vessel was unsuitable for the transportation of Robots; and we are therefore not responsible for spoiled freight. We beg to remain, for Rossum’s Universal Robots, yours truly.”

(SULLA types the lines.)

Ready?

SULLA

Yes.

DOMIN

Another letter. To the E. B. Huysen Agency, New York, U.S.A. “We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for five thousand Robots. As you are sending your own vessel, please dispatch as cargo equal quantities of soft and hard coal for R.U.R., the same to be credited as part payment

(BUZZER)

of the amount due us.

(Answering phone)

Hello! This is the central office. Yes, certainly. Well, send them a wire. Good.

(Rises)

“We beg to remain, for Rossum’s Universal Robots, yours very truly.” Ready?

SULLA

Yes.

DOMIN (Answering small portable phone)

Hello! Yes. No. All right.

(Standing back of desk, punching plug machine and buttons)

Another letter. Freidrichswerks, Hamburg, Germany. “We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for fifteen thousand Robots.”

(Enter MARIUS R.)

Well, what is it?

MARIUS

There’s a lady, sir, asking to see you.

DOMIN

A lady? Who is she?

MARIUS

I don’t know, sir. She brings this card of introduction.

DOMIN (Reading card)

Ah, from President Glory. Ask her to come in—

(To SULLA Crossing up to her desk, then back to his own)

Where did I leave off?

SULLA

“We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for fifteen thousand Robots.”

DOMIN

Fifteen thousand. Fifteen thousand.

MARIUS (At door R.)

Please step this way.

(Enter HELENA Exit MARIUS R.)

HELENA (Crossing to desk)

How do you do?

DOMIN

How do you do? What can I do for you?

HELENA

You are Mr. Domin, the General Manager?

DOMIN

I am.

HELENA

I have come—

DOMIN

With President Glory’s card. That is quite sufficient.

HELENA

President Glory is my father. I am Helena Glory.

DOMIN

Please sit down. Sulla, you may go.

(Exit SULLA L.)

DOMIN (Sitting down L. of desk)

How can I be of service to you, Miss Glory?

HELENA

I have come—

(Sits R. of desk.)

DOMIN

To have a look at our famous works where people are manufactured. Like all visitors. Well, there is no objection.

HELENA

I thought it was forbidden to—

DOMIN

To enter the factory? Yes, of course. Everybody comes here with someone’s visiting card, Miss Glory.

HELENA

And you show them—

DOMIN

Only certain things. The manufacture of artificial people is a secret process.

HELENA

If you only knew how enormously that—

DOMIN

Interests you. Europe’s talking about nothing else.

HELENA (Indignantly turning front)

Why don’t you let me finish speaking?

DOMIN (Drier)

I beg your pardon. Did you want to say something different?

HELENA

I only wanted to ask—

DOMIN

Whether I could make a special exception in your case and show you our factory. Why, certainly, Miss Glory.

HELENA

How do you know I wanted to say that?

DOMIN

They all do. But we shall consider it a special honor to show you more than we do the rest.

HELENA

Thank you.

DOMIN (Standing)

But you must agree not to divulge the least—

HELENA (Standing and giving him her hand)

My word of honor.

DOMIN

Thank you.

(Looking at her hand)

Won’t you raise your veil?

HELENA

Of course. You want to see whether I’m a spy or not—I beg your pardon.

DOMIN (Leaning forward)

What is it?

HELENA

Would you mind releasing my hand?

DOMIN (Releasing it)

Oh, I beg your pardon.

HELENA (Raising veil)

How cautious you have to be here, don’t you?

DOMIN (Observing her with deep interest)

Why, yes. Hm—of course—We—that is—

HELENA

But what is it? What’s the matter?

DOMIN

I’m remarkably pleased. Did you have a pleasant crossing?

HELENA

Yes.

DOMIN

No difficulty?

HELENA

Why?

DOMIN

What I mean to say is—you’re so young.

HELENA

May we go straight into the factory?

DOMIN

Yes. Twenty–two, I think.

HELEN

A Twenty–two what?

DOMIN

Years.

HELENA

Twenty–one. Why do you want to know?

DOMIN

Well, because—as—

(Sits on desk nearer her)

You will make a long stay, won’t you?

HELENA (Backing away R.)

That depends on how much of the factory you show me.

DOMIN (Rises; crosses to her)

Oh, hang the factory. Oh, no, no, you shall see everything, Miss Glory. Indeed you shall. Won’t you sit down?

(Takes her to couch R.C. She sits. Offers her cigarette from case at end of sofa. She refuses.)

HELENA

Thank you.

DOMIN

But first would you like to hear the story of the invention?

HELENA

Yes, indeed.

DOMIN (Crosses to L.C. near desk)

It was in the year 1920 that old Rossum, the great physiologist, who was then quite a young scientist, took himself to the distant island for the purpose of studying the ocean fauna.

(She is amused.)

On this occasion he attempted by chemical synthesis to imitate the living matter known as protoplasm until he suddenly discovered a substance which behaved exactly like living matter although its chemical composition was different. That was in the year 1932, exactly four hundred and forty years after the discovery of America. Whew—

HELENA

Do you know that by heart?

DOMIN (Takes flowers from desk to her)

Yes. You see, physiology is not in my line. Shall I go on?

HELENA (Smelling flowers)

Yes, please.

DOMIN (Center)

And then, Miss Glory, Old Rossum wrote the following among his chemical experiments: “Nature has found only one method of organizing living matter. There is, however, another method, more simple, flexible and rapid which has not yet occurred to Nature at all. This second process by which life can be developed was discovered by me today.” Now imagine him, Miss Glory, writing those wonderful words over some colloidal mess that a dog wouldn’t look at. Imagine him sitting over a test tube and thinking how the whole tree of life would grow from him, how all animals would proceed from it, beginning with some sort of a beetle and ending with a man. A man of different substance from us. Miss Glory, that was a tremendous moment.

(Gets box of candy from desk and passes it to her.)

HELENA

Well—

DOMIN (As she speaks his portable PHONE lights up and he answers)

Well—Hello!—Yes—no, I’m in conference. Don’t disturb me.

HELENA

Well?

DOMIN (Smile)

Now, the thing was how to get the life out of the test tubes, and hasten development and form organs, bones and nerves, and so on, and find such substances as catalytics, enzymes, hormones in short—you understand?

HELENA

Not much, I’m afraid.

DOMIN

Never mind.

(Leans over couch and fixes cushion for her back)

There! You see with the help of his tinctures he could make whatever he wanted. He could have produced a Medusa with the brain of Socrates or a worm fifty yards long—

(She laughs. He does also; leans closer on couch, then straightens up again)

—but being without a grain of humor, he took into his head to make a vertebrate or perhaps a man. This artificial living matter of his had a raging thirst for life. It didn’t mind being sown or mixed together. That couldn’t be done with natural albumen. And that’s how he set about it.

HELENA

About what?

DOMIN

About imitating Nature. First of all he tried making an artificial dog. That took him several years and resulted in a sort of stunted calf which died in a few days. I’ll show it to you in the museum. And then old Rossum started on the manufacture of man.

HELENA

And I’m to divulge this to nobody?

DOMIN

To nobody in the world.

HELENA

What a pity that it’s to be discovered in all the school books of both Europe and America.

(BOTH laugh.)

DOMIN

Yes. But do you know what isn’t in the school books? That old Rossum was mad. Seriously, Miss Glory, you must keep this to yourself. The old crank wanted to actually make people.

HELENA

But you do make people.

DOMIN

Approximately—Miss Glory. But old Rossum meant it literally. He wanted to become a sort of scientific substitute for God. He was a fearful materialist, and that’s why he did it all. His sole purpose was nothing more or less than to prove that God was no longer necessary.

(Crosses to end of couch)

Do you know anything about anatomy?

HELENA

Very little.

DOMIN

Neither do I. Well—

(He laughs)

—he then decided to manufacture everything as in the human body. I’ll show you in the museum the bungling attempt it took him ten years to produce. It was to have been a man, but it lived for three days only. Then up came young Rossum, an engineer. He was a wonderful fellow, Miss Glory. When he saw what a mess of it the old man was making he said: “It’s absurd to spend ten years making a man. If you can’t make him quicker than Nature, you might as well shut up shop.” Then he set about learning anatomy himself.

HELENA

There’s nothing about that in the school books?

DOMIN

No. The school books are full of paid advertisements, and rubbish at that. What the school books say about the united efforts of the two great Rossums is all a fairy tale. They used to have dreadful rows. The old atheist hadn’t the slightest conception of industrial matters, and the end of it was that Young Rossum shut him up in some laboratory or other and let him fritter the time away with his monstrosities while he himself started on the business from an engineer’s point of view. Old Rossum cursed him and before he died he managed to botch up two physiological horrors. Then one day they found him dead in the laboratory. And that’s his whole story.

HELENA

And what about the young man?

DOMIN (Sits beside her on couch)

Well, anyone who has looked into human anatomy will have seen at once that man is too complicated, and that a good engineer could make him more simply. So young Rossum began to overhaul anatomy to see what could be left out or simplified. In short—But this isn’t boring you, Miss Glory?

HELENA

No, indeed. You’re—It’s awfully interesting.

DOMIN (Gets closer)

So young Rossum said to himself: “A man is something that feels happy, plays the piano, likes going for a walk, and, in fact, wants to do a whole lot of things that are really unnecessary.”

HELENA

Oh.

DOMIN

That are unnecessary when he wants—

(Takes her hand)

—let us say, to weave or count. Do you play the piano?

HELENA

Yes.

DOMIN

That’s good.

(Kisses her hand. She lowers her head.)

Oh, I beg your pardon!

(Rises)

But a working machine must not play the piano, must not feel happy, must not do a whole lot of other things. A gasoline motor must not have tassels or ornaments, Miss Glory. And to manufacture artificial workers is the same thing as the manufacture of a gasoline motor.

(She is not interested.)

The process must be the simplest, and the product the best from a practical point of view.

(Sits beside her again)

What sort of worker do you think is the best from a practical point of view?

HELENA (Absently)

What?

(Looks at him.)

DOMIN

What sort of worker do you think is the best from a practical point of view?

HELENA (Pulling herself together)

Oh! Perhaps the one who is most honest and hard-working.

DOMIN

No. The one that is the cheapest. The one whose requirements are the smallest. Young Rossum invented a worker with the minimum amount of requirements. He had to simplify him. He rejected everything that did not contribute directly to the progress of work. Everything that makes man more expensive. In fact he rejected man and made the Robot. My dear Miss Glory, the Robots are not people. Mechanically they are more perfect than we are; they have an enormously developed intelligence, but they have no soul.

(Leans back.)

HELENA

How do you know they have no soul?

DOMIN

Have you ever seen what a Robot looks like inside?

HELENA

No.

DOMIN

Very neat, very simple. Really a beautiful piece of work. Not much in it, but everything in flawless order. The product of an engineer is technically at a higher pitch of perfection than a product of Nature.

HELENA

But man is supposed to be the product of God.

DOMIN

All the worse. God hasn’t the slightest notion of modern engineering. Would you believe that young Rossum then proceeded to play at being God?

HELENA (Awed)

How do you mean?

DOMIN

He began to manufacture Super-Robots. Regular giants they were. He tried to make them twelve feet tall. But you wouldn’t believe what a failure they were.

HELENA

A failure?

DOMIN

Yes. For no reason at all their limbs used to keep snapping off. “Evidently our planet is too small for giants.” Now we only make Robots of normal size and of very high-class human finish.

HELENA (Hands him flower; he puts it in button-hole)

I saw the first Robots at home. The Town Council bought them for—I mean engaged them for work.

DOMIN

No. Bought them, Miss Glory. Robots are bought and sold.

HELENA

These were employed as street-sweepers. I saw them sweeping. They were so strange and quiet.

DOMIN (Rises)

Rossum’s Universal Robot factory doesn’t produce a uniform brand of Robots. We have Robots of finer and coarser grades. The best will live about twenty years.

(Crosses to desk.HELENA looks in her pocket mirror. He pushes button on desk.)

HELENA

Then they die?

DOMIN

Yes, they get used up.

(Enter MARIUS, R. DOMIN crosses to C.)

Marius, bring in samples of the manual labor Robot.

(Exit MARIUS R.C.)

I’ll show you specimens of the two extremes. This first grade is comparatively inexpensive and is made in vast quantities.

(MARIUS re-enters R.C. with two manual labor ROBOTS. MARIUS is L.C., ROBOTS R.C., DOMIN at desk. MARIUS stands on tiptoes, touches head, feels arms, forehead of one of the ROBOTS. They come to a mechanical standstill.)

There you are, as powerful as a small tractor. Guaranteed to have average intelligence. That will do, Marius.

(MARIUS exits R.C.with ROBOTS.)

HELENA

They make me feel so strange.

DOMIN (Crosses to desk. Rings)

Did you see my new typist?

HELENA

I didn’t notice her.

(Enter SULLA L. She crosses and stands C., facing HELENA, who is still sitting in the couch.)

DOMIN

Sulla, let Miss Glory see you.

HELENA (Looks at DOMIN Rising, crosses a step to C.)

So pleased to meet you.

(Looks at DOMIN)

You must find it terribly dull in this out of the way spot, don’t you?

SULLA

I don’t know, Miss Glory.

HELENA

Where do you come from?

SULLA

From the factory.

HELENA

Oh, were you born there?

SULLA

I was made there.

HELENA

What?

(Looks first at SULLA, then at DOMIN)

DOMIN (To SULLA, laughing)

Sulla is a Robot, best grade.

HELENA

Oh, I beg your pardon.

DOMIN (Crosses to SULLA)

Sulla isn’t angry. See, Miss Glory, the kind of skin we make. Feel her face.

(Touches SULLA’S face.)

HELENA

Oh, no, no.

DOMIN (Examining SULLA’S hand)

You wouldn’t know that she’s made of different material from us, would you? Turn ’round, Sulla.

(SULLA does so. Circles twice.)

HELENA

Oh, stop, stop.

DOMIN

Talk to Miss Glory, Sulla.

(Examines hair of SULLA)

SULLA

Please sit down.

(HELENA sits on couch.)

Did you have a pleasant crossing?

(Fixes her hair.)

HELENA

Oh, yes, certainly.

SULLA

Don’t go back on the Amelia, Miss Glory, the barometer is falling steadily. Wait for the Pennsylvania. That’s a good powerful vessel.

DOMIN

What’s its speed?

SULLA

Forty knots an hour. Fifty thousand tons. One of the latest vessels, Miss Glory.

HELENA

Thank you.

SULLA

A crew of fifteen hundred, Captain Harpy, eight boilers—

DOMIN

That’ll do, Sulla. Now show us your knowledge of French.

HELENA

You know French?

SULLA

Oui! Madame! I know four languages. I can write: “Dear Sir, Monsieur, Geehrter Herr, Cteny pane.”

HELENA (Jumping up, crosses to SULLA)

Oh, that’s absurd! Sulla isn’t a Robot. Sulla is a girl like me. Sulla, this is outrageous—Why do you take part in such a hoax?

SULLA

I am a Robot.

HELENA

No, no, you are not telling the truth.

(She catches the amused expression on DOMIN’S face)

I know they have forced you to do it for an advertisement. Sulla, you are a girl like me, aren’t you?

(Looks at him.)

DOMIN

I’m sorry, Miss Glory. Sulla is a Robot.

HELENA

It’s a lie!

DOMIN

What?

(Pushes button on desk)

Well, then I must convince you.

(Enter MARIUS R.C. He stands just inside the door.)

Marius, take Sulla into the dissecting room, and tell them to open her up at once.

(MARIUS moves toward C.)

HELENA

Where?

DOMIN

Into the dissecting room. When they’ve cut her open, you can go and have a look.

(MARIUS makes a start toward SULLA)

HELENA (Stopping MARIUS)

No! No!

DOMIN

Excuse me, you spoke of lies.

HELENA

You wouldn’t have her killed?

DOMIN

You can’t kill machines. Sulla!

(MARIUS one step forward, one arm out. SULLA makes a move toward R. door.)

HELENA (Moves a step R.)

Don’t be afraid, Sulla. I won’t let you go. Tell me, my dear—

(Takes her hand)

—are they always so cruel to you? You mustn’t put up with it, Sulla. You mustn’t.

SULLA

I am a Robot.

HELENA

That doesn’t matter. Robots are just as good as we are. Sulla, you wouldn’t let yourself be cut to pieces?

SULLA

Yes.

(Hand away.)

HELENA

Oh, you’re not afraid of death, then?

SULLA

I cannot tell, Miss Glory.

HELENA

Do you know what would happen to you in there?

SULLA

Yes, I should cease to move.

HELENA

How dreadful!

(Looks at SULLA)

DOMIN

Marius, tell Miss Glory what you are?

(Turns to HELENA)

MARIUS (To HELENA)

Marius, the Robot.

DOMIN

Would you take Sulla into the dissecting room?

MARIUS (Turns to DOMIN)

Yes.

DOMIN

Would you be sorry for her?

MARIUS (Pause)

I cannot tell.

DOMIN

What would happen to her?

MARIUS

She would cease to move. They would put her into the stamping mill.

DOMIN

That is death, Marius. Aren’t you afraid of death?

MARIUS

No.

DOMIN

You see, Miss Glory, the Robots have no interest in life. They have no enjoyments. They are less than so much grass.

HELENA

Oh, stop. Please send them away.

DOMIN (Pushes button)

Marius, Sulla, you may go.

(MARIUS pivots and exits R. SULLA exits L.)

HELENA How terrible!

(To C.)

It’s outrageous what you are doing.

(He takes her hand.)

DOMIN

Why outrageous?

(His hand over hers. Laughing.)

HELENA

I don’t know, but it is. Why do you call her “Sulla”?

DOMIN

Isn’t it a nice name?

(Hand away.)

HELENA

It’s a man’s name. Sulla was a Roman General.

DOMIN

What! Oh!

(Laughs)

We thought that Marius and Sulla were lovers.

HELENA (Indignantly)

Marius and Sulla were generals and fought against each other in the year—I’ve forgotten now.

DOMIN (Laughing)

Come here to the window.

(He goes to window C.)

HELENA

What?

DOMIN

Come here.

(She goes.)

Do you see anything?

(Takes her arm. She is on his R.)

HELENA

Bricklayers.

DOMIN

Robots. All our work people are Robots. And down there, can you see anything?

HELENA

Some sort of office.

DOMIN

A counting house. And in it—

HELENA

A lot of officials.

DOMIN

Robots! All our officials are Robots. And when you see the factory—

(Noon WHISTLE blows. She is scared; puts arm on DOMIN. He laughs)

If we don’t blow the whistle the Robots won’t stop working. In two hours I’ll show you the kneading trough.

(BOTH come down stage. HELENA is L.C. and DOMIN is R.C., arm in arm.)

HELENA

Kneading trough?

DOMIN

The pestle for beating up the paste. In each one we mix the ingredients for a thousand Robots at one operation. Then there are the vats for the preparation of liver, brains, and so on. Then you will see the bone factory. After that I’ll show you the spinning mill.

HELENA

Spinning mill?

DOMIN

Yes. For weaving nerves and veins. Miles and miles of digestive tubes pass through it at a time.

HELENA (Watching his gestures)

Mayn’t we talk about something else?

DOMIN

Perhaps it would be better. There’s only a handful of us among a hundred thousand Robots, and not one woman. We talk nothing but the factory all day, and every day. It’s just as if we were under a curse, Miss Glory.

HELENA I’m sorry I said that you were lying.

(A KNOCK at door R.)

DOMIN Come in.

(He is C.)

(From R. enter DR. GALL, DR. FABRY, ALQUIST and DR. HALLEMEIER. ALL act formal—conscious. ALL click heels as introduced.)

DR. GALL. (Noisily)

I beg your pardon. I hope we don’t intrude.

DOMIN

No, no. Come in. Miss Glory, here are Gall, Fabry, Alquist, Hallemeier. This is President Glory’s daughter.

(ALL move to her and shake her hand.)

HELENA

How do you do?

FABRY

We had no idea—

DR. GALL

Highly honored, I’m sure—

ALQUIST

Welcome, Miss Glory.

BUSMAN (Rushes in from R.)

Hello, what’s up?

DOMIN

Come in, Busman. This is President Glory’s daughter. This is Busman, Miss Glory.

BUSMAN

By Jove, that’s fine.

(ALL click heels. He crowds in and shakes her hand)

Miss Glory, may we send a cablegram to the papers about your arrival?

HELENA

No, no, please don’t.

DOMIN

Sit down, please, Miss Glory.

(On the line, “Sit down, please,” all SIX MEN try to find her a chair at once. HELENA goes for the chair at the extreme L. DOMIN takes the chair at front of desk, places it in the C. of stage. HALLEMEIER gets chair at SULLA’S typewriter and places it to R. of chair at C. BUSMAN gets armchair from extreme R., but by now HELENA has sat in DOMIN’S preferred chair, at C. ALL sit except DOMIN. BUSMAN at R. in armchair. HALLEMEIER R. of HELENA. FABRY in swivel chair back of desk.)

BUSMAN

Allow me—

DR. GALL

Please—

FABRY

Excuse me—

ALQUIST

What sort of a crossing did you have?

DR. GAL

Are you going to stay long?

(MEN conscious of their appearance. ALQUIST’S trousers turned up at bottom. He turns them down. BUSMAN polishes shoes. OTHERS fix ties, collars, etc.)

FABRY

What do you think of the factory, Miss Glory?

HALLEMEIER

Did you come over on the Amelia?

DOMIN

Be quiet and let Miss Glory speak.

(MEN sit erect. DOMIN stands at HELENA’S L.)

HELENA (To DOMIN)

What am I to speak to them about?

(MEN look at one another.)

DOMIN

Anything you like.

HELENA (Looks at DOMIN)

May I speak quite frankly?

DOMIN

Why, of course.

HELENA (To OTHERS. Wavering, then in desperate resolution)

Tell me, doesn’t it ever distress you the way you are treated?

FABRY

By whom, may I ask?

HELENA

Why, everybody.

ALQUIST

Treated?

DR. GALL

What makes you think—

HELENA

Don’t you feel that you might be living a better life?

(Pause. ALL confused.)

DR. GALL (Smiling)

Well, that depends on what you mean, Miss Glory.

HELENA

I mean that it’s perfectly outrageous. It’s terrible.

(Standing up)

The whole of Europe is talking about the way you’re being treated. That’s why I came here, to see for myself, and it’s a thousand times worse than could have been imagined. How can you put up with it?

ALQUIST

Put up with what?

HELENA

Good heavens, you are living creatures, just like us, like the whole of Europe, like the whole world. It’s disgraceful that you must live like this.

BUSMAN

Good gracious, Miss Glory!

FABRY

Well, she’s not far wrong. We live here just like red Indians.

HELENA

Worse than red Indians. May I—oh, may I call you—brothers?

(MEN look at each other.)

BUSMAN

Why not?

HELENA (Looking at DOMIN)

Brothers, I have not come here as the President’s daughter. I have come on behalf of the Humanity League. Brothers, the Humanity League now has over two hundred thousand members. Two hundred thousand people are on your side, and offer you their help.

(Tapping back of chair.)

BUSMAN

Two hundred thousand people, Miss Glory; that’s a tidy lot. Not bad.

FABRY

I’m always telling you there’s nothing like good old Europe. You see they’ve not forgotten us. They’re offering us help.

DR. GALL

What kind of help? A theatre, for instance?

HALLEMEIER

An orchestra?

HELENA

More than that.

ALQUIST

Just you?

HELENA (Glaring at DOMIN)

Oh, never mind about me. I’ll stay as long as it is necessary.

(ALL express delight.)

BUSMAN

By Jove, that’s good.

ALQUIST (Rising L.)

Domin, I’m going to get the best room ready for Miss Glory.

DOMIN

Just a minute. I’m afraid that Miss Glory is of the opinion she has been talking to Robots.

HELENA

Of course.

(MEN laugh.)

DOMIN

I’m sorry. These gentlemen are human beings just like us.

HELENA

You’re not Robots?

| BUSMAN Not Robots. |

} |

| } | |

| HALLEMEIER Robots indeed! |

} |

| } (All together) | |

| DR. GALL No, thanks. |

} |

| } | |

FABRY |

} |

HELENA

Then why did you tell me that all your officials are Robots?

DOMIN

Yes, the officials, but not the managers. Allow me, Miss Glory—this is Consul Busman, General Business Manager; this is Doctor Fabry, General Technical Manager; Doctor Hallemeier, head of the Institute for the Psychological Training of Robots; Doctor Gall, head of the Psychological and Experimental Department; and Alquist, head of the Building Department, R. U. R.

(As they are introduced they rise and come C. to kiss her hand, except GALL and ALQUIST, whom DOMIN pushes away. General babble.)

ALQUIST

Just a builder. Please sit down.

HELENA

Excuse me, gentlemen. Have I done something dreadful?

ALQUIST

Not at all, Miss Glory.

BUSMAN (Handing flowers)

Allow me, Miss Glory.

HELENA

Thank you.

FABRY (Handing candy)

Please, Miss Glory.

DOMIN

Will you have a cigarette, Miss Glory?

HELENA

No, thank you.

DOMIN

Do you mind if I do?

HELENA

Certainly not.

BUSMAN

Well, now, Miss Glory, it is certainly nice to have you with us.

HELENA (Seriously)

But you know I’ve come to disturb your Robots for you.

(BUSMAN pulls chair closer.)

DOMIN (Mocking her serious tone)

My dear Miss Glory—

(Chuckle)

—we’ve had close upon a hundred saviors and prophets here. Every ship brings us some. Missionaries, Anarchists, Salvation Army, all sorts! It’s astonishing what a number of churches and idiots there are in the world.

HELENA

And yet you let them speak to the Robots.

DOMIN

So far we’ve let them all. Why not? The Robot remembers everything but that’s all. They don’t even laugh at what the people say. Really it’s quite incredible.

HELENA

I’m a stupid girl. Send me back by the first ship.

DR. GALL

Not for anything in the world, Miss Glory. Why should we send you back?

DOMIN

If it would amuse you, Miss Glory, I’ll take you down to the Robot warehouse. It holds about three hundred thousand of them.

BUSMAN

Three hundred and forty-seven thousand.

DOMIN

Good, and you can say whatever you like to them. You can read the Bible, recite the multiplication table, whatever you please. You can even preach to them about human rights.

HELENA

Oh, I think that if you were to show them a little love.

FABRY

Impossible, Miss Glory! Nothing is harder to like than a Robot.

HELENA

What do you make them for, then?

BUSMAN

Ha, ha, ha! That’s good. What are Robots made for?

FABRY

For work, Miss Glory. One Robot can replace two and a half workmen. The human machine, Miss Glory, was terribly imperfect. It had to be removed sooner or later.

BUSMAN

It was too expensive.

FABRY

It was not effective. It no longer answers the requirements of modern engineering. Nature has no idea of keeping pace with modern labor. For example, from a technical point of view, the whole of childhood is a sheer absurdity. So much time lost. And then again—

HELENA (Turns to DOMIN)

Oh, no, no!

FABRY

Pardon me. What is the real aim of your League—the—the Humanity League?

HELENA

Its real purpose is to—to protect the Robots—and—and to insure good treatment for them.

FABRY

Not a bad object, either. A machine has to be treated properly.

(Leans back)

I don’t like damaged articles. Please, Miss Glory, enroll us all members of your league.

(“Yes, yes!” from all MEN.)

HELENA

No, you don’t understand me. What we really want is to—to—liberate the Robots.

(Looks at all OTHERS.)

HALLEMEIER

How do you propose to do that?

HELENA

They are to be—to be dealt with like human beings.

HALLEMEIER

Aha! I suppose they’re to vote. To drink beer. To order us about?

HELENA

Why shouldn’t they drink beer?

HALLEMEIER

Perhaps they’re even to receive wages?

(Looking at other MEN, amused.)

HELENA

Of course they are.

HALLEMEIER

Fancy that! Now! And what would they do with their wages,pray?

HELENA

They would buy—what they want—what pleases them.

HALLEMEIER

That would be very nice, Miss Glory, only there’s nothing that does please the Robots. Good heavens, what are they to buy? You can feed them on pineapples, straw, whatever you like. It’s all the same to them. They’ve no appetite at all. They’ve no interest in anything. Why, hang it all, nobody’s ever yet seen a Robot smile.

HELENA

Why—why don’t you make them—happier?

HALLEMEIER

That wouldn’t do, Miss Glory. They are only workmen.

HELENA

Oh, but they’re so intelligent.

HALLEMEIER

Confoundedly so, but they’re nothing else. They’ve no will of their own. No soul. No passion.

HELENA

No love?

HALLEMEIER

Love? Huh! Rather not. Robots don’t love. Not even themselves.

HELENA

No defiance?

HALLEMEIER

Defiance? I don’t know. Only rarely, from time to time.

HELENA

What happens then?

HALLEMEIER

Nothing particular. Occasionally they seem to go off their heads. Something like epilepsy, you know. It’s called “Robot’s Cramp.” They’ll suddenly sling down everything they’re holding, stand still, gnash their teeth—and then they have to go into the stamping-mill. It’s evidently some breakdown in the mechanism.

DOMIN (Sitting on desk)

A flaw in the works that has to be removed.

HELENA

No, no, that’s the soul.

FABRY (Humorously)

Do you think that the soul first shows itself by a gnashing of teeth?

(MEN chuckle.)

HELENA

Perhaps it’s just a sign that there’s a struggle within. Perhaps it’s a sort of revolt. Oh, if you could infuse them with it.

DOMIN

That’ll be remedied, Miss Glory. Doctor Gall is just making some experiments.

DR. GALL

Not with regard to that, Domin. At present I am making pain nerves.

HELENA

Pain nerves?

DR. GALL

Yes, the Robots feel practically no bodily pain. You see, young Rossum provided them with too limited a nervous system. We must introduce suffering.

HELENA

Why do you want to cause them pain?

DR. GALL

For industrial reasons, Miss Glory. Sometimes a Robot does damage to himself because it doesn’t hurt him. He puts his hand into the machine—

(Describes with gesture)

—breaks his finger—

(Describes with gesture)

—smashes his head. It’s all the same to him. We must provide them with pain. That’s an automatic protection against damage.

HELENA

Will they be happier when they feel pain?

DR. GALL

On the contrary; but they will be more perfect from a technical point of view.

HELENA

Why don’t you create a soul for them?

DR. GALL

That’s not in our power.

FABRY

That’s not in our interest.

BUSMAN

That would increase the cost of production. Hang it all, my dear young lady, we turn them out at such a cheap rate—a hundred and fifty dollars each, fully dressed, and fifteen years ago they cost ten thousand. Five years ago we used to buy the clothes for them. Today we have our own weaving mill, and now we even export cloth five times cheaper than other factories. What do you pay a yard for cloth, Miss Glory?

HELENA (Looking at DOMIN)

I don’t really know. I’ve forgotten.

BUSMAN

Good gracious, and you want to found a Humanity League.

(MEN chuckle.)

It only costs a third now, Miss Glory. All prices are today a third of what they were and they’ll fall still lower, lower, like that.

HELENA

I don’t understand.

BUSMAN

Why, bless you, Miss Glory, it means that the cost of labor has fallen. A Robot, food and all, costs three-quarters of a cent per hour.

(Leans forward)

That’s mighty important, you know. All factories will go pop like chestnuts if they don’t at once buy Robots to lower the cost of production.

HELENA

And get rid of all their workmen?

BUSMAN

Of course. But in the meantime we’ve dumped five hundred thousand tropical Robots down on the Argentine pampas to grow corn. Would you mind telling me how much you pay a pound for bread?

HELENA

I’ve no idea.

(ALL smile.)

BUSMAN

Well, I’ll tell you. It now costs two cents in good old Europe. A pound of bread for two cents, and the Humanity League—

(Designates HELENA)

—knows nothing about it.

(To MEN)

Miss Glory, you don’t realize that even that’s too expensive.

(All MEN chuckle.)

Why, in five years’ time I’ll wager—

HELENA

What?

BUSMAN

That the cost of everything will be a tenth of what it is today. Why, in five years we’ll be up to our ears in corn and—everything else.

ALQUIST

Yes, and all the workers throughout the world will be unemployed.

DOMIN (Seriously. Rises)

Yes, Alquist, they will. Yes, Miss Glory, they will. But in ten years Rossum’s Universal Robots will produce so much corn, so much cloth, so much everything that things will be practically without price. There will be no poverty. All work will be done by living machines. Everybody will be free from worry and liberated from the degradation of labor. Everybody will live only to perfect himself.

HELENA

Will he?

DOMIN

Of course. It’s bound to happen. Then the servitude of man to man and the enslavement of man to matter will cease. Nobody will get bread at the cost of life and hatred. The Robots will wash the feet of the beggar and prepare a bed for him in his house.

ALQUIST

Domin, Domin, what you say sounds too much like Paradise. There was something good in service and something great in humility. There was some kind of virtue in toil and weariness.

DOMIN

Perhaps, but we cannot reckon with what is lost when we start out to transform the world. Man shall be free and supreme; he shall have no other aim, no other labor, no other care than to perfect himself. He shall serve neither matter nor man. He will not be a machine and a device for production. He will be Lord of creation.

BUSMAN

Amen.

FABRY

So be it.

HELENA (Rises)

You have bewildered me. I should like to believe this.

DR. GALL

You are younger than we are, Miss Glory. You will live to see it.

HALLEMEIER

True.

(Looking around)

Don’t you think Miss Glory might lunch with us?

(All MEN rise.)

DR. GALL

Of course. Domin, ask her on behalf of us all.

DOMIN

Miss Glory, will you do us the honor?

HELENA

When you know why I’ve come?

FABRY

For the League of Humanity, Miss Glory.

HELENA

Oh, in that case perhaps—

FABRY

That’s fine.

(Pause)

Miss Glory, excuse me for five minutes.

(Exits R.)

HALLEMEIER

Thank you.

(Exits R. with DR. GALL.)

BUSMAN (Whispering)

I’ll be back soon.

(Beckoning to ALQUIST, they exit.)

ALQUIST (Starts, stops, then to HELENA, then to door)

I’ll be back in exactly five minutes.

(Exits R.)

HELENA What have they all gone for?

DOMIN

To cook, Miss Glory.

(On her L.)

HELENA

To cook what?

DOMIN

Lunch.

(They laugh; takes her hand)

The Robots do our cooking for us and as they’ve no taste it’s not altogether—

(She laughs.)

Hallemeier is awfully good at grills and Gall can make any kind of sauce, and Busman knows all about omelets.

HELENA

What a feast! And what’s the specialty of Mr.—your builder?

DOMIN

Alquist? Nothing. He only lays the table. And Fabry will get together a little fruit. Our cuisine is very modest, Miss Glory.

HELENA (Thoughtfully)

I wanted to ask you something—

DOMIN

And I wanted to ask you something too—they’ll be back in five minutes.

(Looks at door R.)

HELENA

What did you want to ask me?

(Sits C.)

DOMIN

Excuse me, you asked first.

(Sits L. of her.)

HELENA

Perhaps it’s silly of me, but why do you manufacture female Robots when—when—

DOMIN

When sex means nothing to them?

HELENA

Yes.

DOMIN

There’s a certain demand for them, you see. Servants, saleswomen, stenographers. People are used to it.

HELENA

But—but tell me, are the Robots male and female, mutually—completely without—

DOMIN

Completely indifferent to each other, Miss Glory. There’s no sign of any affection between them.

HELENA

Oh, that’s terrible.

DOMIN

Why?

HELENA

It’s so unnatural. One doesn’t know whether to be disgusted or to hate them, or perhaps—

DOMIN

To pity them.

(Smiles.)

HELENA

That’s more like it. What did you want to ask me?

DOMIN

I should like to ask you, Miss Helena, if you will marry me.

HELENA

What?

(Rises.)

DOMIN

Will you be my wife?

(Rises.)

HELENA

No. The idea!

DOMIN (To her, looking at his watch)

Another three minutes. If you don’t marry me you’ll have to marry one of the other five.

HELENA

But why should I?

DOMIN

Because they’re all going to ask you in turn.

HELENA (Crossing him to L.C.)

How could they dare do such a thing?

DOMIN

I’m very sorry, Miss Glory. It seems they’ve fallen in love with you.

HELENA

Please don’t let them. I’ll—I’ll go away at once.

(Starts R. He stops her, his arms up.)

DOMIN

Helena—

(She backs away to desk. He follows)

You wouldn’t be so cruel as to refuse us.

HELENA

But, but—I can’t marry all six.

DOMIN

No, but one anyhow. If you don’t want me, marry Fabry.

HELENA

I won’t.

DOMIN

Ah! Doctor Gall?

HELENA

I don’t want any of you.

DOMIN

Another two minutes.

(Pleading. Looking at watch.)

HELENA

I think you’d marry any woman who came here.

DOMIN

Plenty of them have come, Helena.

HELENA (Laughing)

Young?

DOMIN

Yes.

HELENA

Why didn’t you marry one of them?

DOMIN

Because I didn’t lose my head. Until today—then as soon as you lifted your veil—

(HELENA turns her head away.)

Another minute.

(WARN Curtain.)

HELENA

But I don’t want you, I tell you.

DOMIN (Laying both hands on her shoulder)

One more minute! Now you either have to look me straight in the eye and say “no” violently, and then I leave you alone—or—

(HELENA looks at him. He takes hands away. She takes his hand again.)

HELENA (Turning her head away)

You’re mad.

DOMIN

A man has to be a bit mad, Helena. That’s the best thing about him.

(He draws her to him.)

HELENA (Not meaning it)

You are—you are—

DOMIN

Well?

HELENA

Don’t, you’re hurting me!

DOMIN

The last chance, Helena. Now or never—

HELENA

But—but—

(He embraces her; kisses her. She embraces him. KNOCKING at R. door.)

DOMIN (Releasing her)

Come in.

(She lays her head on his shoulder. Enter BUSMAN, GALL and HALLEMEIER in kitchen aprons, FABRY with a bouquet and ALQUIST with a napkin under his arm.)

DOMIN

Have you finished your job?

BUSMAN

Yes.

DOMIN

So have we.

(He embraces her. The MEN rush around them and offer congratulations.)

THE CURTAIN FALLS QUICKLY