|

DAN O’BRIEN

The Dear Boy

|

|

| |

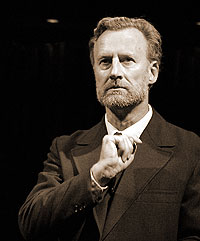

Daniel Gerroll as Flanagan |

| Photo by Richard Termine |

4.

(Next morning.

FLANAGAN stands at his desk, dressed as he’s been all night; he’s put his tie back on.

Sunlight grows in the window, all throughout the scene.

He takes the gun from his pocket, lays it gently down upon the desk, beside James’ story . . .

He sits down.

He stares at both the story and the gun . . .

After a while:)

FLANAGAN

I know you’re there.

(JAMES appears in the doorway, out-of-sorts.)

JAMES

I saw your car in the teacher’s lot . . .

FLANAGAN

Were you waiting for me?

Why?

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

It’s Saturday, James—

JAMES

Can I come in?

FLANAGAN

Of course you may, my boy . . .

(JAMES comes in, but remains standing near the door.

FLANAGAN leaves the gun right where it is.)

JAMES

Why didn’t you call the police?

FLANAGAN

. . . ?

JAMES

Last night—

FLANAGAN

I don’t remember. I still might. I’ll have to, won’t I?

JAMES

—Why didn’t you do it in the first place?

FLANAGAN

I don’t know. —I suppose I wanted to give you another chance.

JAMES

A chance for what . . . ?

FLANAGAN

. . .

JAMES

—Can I sit down?

(He does.)

JAMES (cont’d.)

Look: if my father finds out the gun’s gone he’s going to kill me—

FLANAGAN

—You told me all this / yesterday—

JAMES (strongly)

—Why do you always just assume you know everything about everyone . . . ?

FLANAGAN (covering the gun with his hand)

. . .

JAMES

You don’t know everything . . . !

FLANAGAN

. . .

JAMES (pleading, suddenly)

—Can I have it back now?, please? I’m sorry. I promise I won’t hurt you. You can keep the bullets. I get confused. Let’s just forget everything that I said and I’ll put it back where it belongs, and nobody will ever know it was / gone—

FLANAGAN

—Why do you want it back?

JAMES

I told you: my father—

FLANAGAN

Forget all that, James, forget about your father: you wanted to kill me yesterday.

JAMES

No, I didn’t . . .

FLANAGAN

“Mr. Flyswatter”—I was cruel / to you—

JAMES

I didn’t want to kill you—

FLANAGAN

—That was what, then—to frighten me? It worked.

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

—Were you going to use it on someone else?, at school—

JAMES (laughs)

No—

FLANAGAN

Your family?

JAMES

—I don’t want to murder anyone!

FLANAGAN

Don’t you want to tell me something, James?

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

—You want to tell me—. If you don’t want to kill me you want to tell me—

JAMES

Nothing.

FLANAGAN

You don’t want to tell me / anything—

JAMES

No. —I don’t know—

FLANAGAN

You don’t know what’s wrong with you, or you don’t know if you want to tell me?

JAMES

—You’re not my fucking psychiatrist—!

FLANAGAN

—O, I know that—I am well aware that I am not your “fucking psychiatrist”—I’m not trained for any of this—.

Let’s call your / parents now—

JAMES

—The fuck do you care?

FLANAGAN

All right:

JAMES (standing)

—You let me leave here yesterday and you did not think twice—. Call the police if you think I’m a danger to myself.

FLANAGAN

Are you a danger to yourself?

JAMES (the window)

. . .

FLANAGAN

James?

JAMES

I could do it other ways if I wanted—.

I could eat a bottle of aspirin.

(He gestures out the window:)

I could hang myself on one of those fucking cut-up trees—.

FLANAGAN

—Is that what you want to do? Do you want to harm yourself?

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

James:

JAMES

. . . Sometimes.

FLANAGAN

Good:

JAMES

What?

FLANAGAN

Why:

JAMES

—Why what?

FLANAGAN

Why do you want to kill yourself?

JAMES (he laughs)

. . .

FLANAGAN

Do you know . . . ?

JAMES

I know—

FLANAGAN

—Is your life so terrible . . . ?

JAMES

—Why do you say it like that?

FLANAGAN

Like what?

JAMES

—I can’t take it anymore . . .

Okay?

FLANAGAN

—You’re going to have to be a bit more specific than that, James. —What exactly “can’t you take”?

JAMES

Everything—

FLANAGAN

“Everything”?

JAMES

—Life—

FLANAGAN

Life? You can’t take “life” anymore—?

JAMES

—Why are you laughing at me?

FLANAGAN

I’m not—I’m simply—. You’re going to have to be patient with me on this one because, frankly, this is where I begin to lose sympathy for you; this is precisely when I begin to become quite angry with you, if you’ll forgive me. —If you’re going to kill yourself, if you’re not going to give yourself at least the opportunity to let life prove to you that you are wrong, that life has something to offer—that there are people out there in this world who will love you, to some degree, in some way, one day—then you ought to know why.

So tell me:

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN (quietly, very gently)

Tell me, James . . . You’re in pain . . . I will listen to you now . . .

(The boy begins to cry, almost soundlessly.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

. . . Listen: what you said to me, yesterday—. About my story . . . and your story; when you made reference to mine—. —I want you to know that you were right. You were absolutely right about me . . .

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

James: has your father interfered with you before?

JAMES (looking up)

. . . ?

FLANAGAN

Has he abused you—? Has anyone abused / you—?

JAMES (short laugh)

—I’ve never been molested.

FLANAGAN

. . .

JAMES

That’s your story.

FLANAGAN (slumps slowly back in his chair)

. . .

JAMES (wiping his eyes)

. . .

(FLANAGAN watches JAMES for a long time.

Slowly, he pushes the gun across the desk.)

FLANAGAN

You can have it back now. It’s yours. Take it home to your father. Or kill yourself. Don’t do it here.

JAMES (eyes the gun)

. . .

(He makes the slightest move for it—sitting forward in his chair.)

FLANAGAN

Or you can pick up that story instead.

(His fingers lightly brush the pages on the desk.)

. . . I was re-reading it when you came in: it’s not bad. It’s good. I was wrong yesterday; it shows potential . . .

And it would be a shame, in my opinion, after forty-two years of teaching, to see you splatter the brains that could write these words all over the walls of this room. Or any room, for that matter.

JAMES

. . . It’s shit.

FLANAGAN

—It’s not shit—it’s your story—!

(He pushes it across the desk.)

Pick it up and read it out loud and I will show you exactly where I see such promise . . .

JAMES (wipes his eyes; nose)

. . .

FLANAGAN

Go on:

(The boy reaches . . .

For an instant it looks like he might choose the gun.

He picks the story up instead.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

When you are ready, my boy:

JAMES (coughs; wipes nose)

. . . “Saint James: Portrait of a Hero,” by—me.

(A fragile laugh is shared.)

JAMES (cont’d.)

“At the station the sun is angry. The wet tiles of the train station roof gleam and chortle in the morning sun. The snow shrieks and the crows taunt him. James walks through this sea of commuters, these fat men like beetles in their dark wool coats. Watch where you’re going! somebody shouts, and James thinks, They crucified Jesus, too . . . He lives near the station, in the slums of this rich town. His mother lies in bed late into the morning. His father—where is his father? . . . James packs his bag, slips into the morning rush and walks through this sea of people who know nothing about him, nothing of his life or of each other, on his way to school and the sun at least loves his heart—”

FLANAGAN

—There.

JAMES

. . . ?

FLANAGAN

That’s good, isn’t it? . . . That’s very good: “The sun at least loves his heart.”

JAMES

. . .

FLANAGAN

You may continue, dear boy.

(As lights fade:)

JAMES

“At the classroom, Flyswatter stands, tall, effete, brownsuited . . . ”

END OF PLAY

Contributor’s

notes

return to top

|