JESSE ULMER

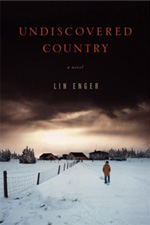

Review | Undiscovered Country, by Lin Enger

|

|

| Little, Brown and Company, 2008 |

Adapting Shakespeare can be a notoriously fickle affair. Part of the risk lies in how the parallels are treated. Bad adaptations are marked by overly careful contrivances—this character represents this character, this event represents this event—until in the end, the adaptation is little more than a Platonic shadow, superficial and airy. When the adaptation succeeds, however, the adaptors, whether individual or group, whether on stage or on the page, can take the pre-existing work and transform it uniquely. Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius, Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, and Smiley’s A Thousand Acres provide notable examples (though the best example of a brilliant adapter is probably Shakespeare himself, arguably one of the greatest narrative cannibalizers of all time).

Well on his way to joining such esteemed company is novelist Lin Enger. His début novel, Undiscovered Country, succeeds precisely where so many adaptations of Shakespeare fail: the story is allowed to assume a life of its own while still harnessing the raw energy of Shakespeare’s dramatic power, a story that stays true to the spirit of the original while also producing something that stands on its own, a work that can be fully enjoyed without ever having experienced the original.

The novel tells the story of seventeen-year-old Jesse Matson, whose father, the mayor and local hero of a small town in Northern Minnesota, suffers a lethal gunshot wound to the head while deer hunting with his son. A suicide, or so it is believed by everyone except Jesse, who discovers the body. This traumatic event dispatches the protagonist on a dark quest to determine whether his father’s death was suicide or fratricide, a product of the pressures of small-town ambition, a faltering marriage, and a childhood plagued by an unloving, distant father, or the result of a long-standing sibling rivalry between his father and uncle.

Readers familiar with Hamlet—a daunting case of retelling, given its place in the pantheon of English literature—know from the outset that Claudius is guilty of King Hamlet’s murder. Yet one of the great pleasures of Enger’s narrative is that it is far from certain at any point that the jealous uncle is guilty of murdering the figurative king. Jesse engineers a series of traps intended to expose Clay as the guilty party, but each one is inconclusive, leaving both Jesse and the reader in a constant state of speculation. The resulting ambiguity helps drive the plot and keeps the reader invested on all levels: emotional, intellectual, visceral. Enger’s exceptional skill with mystery plots, marked by an uncanny ability to keep the reader perpetually within arm’s reach of resolution, is clearly evident throughout the novel. He honed this skill during his many years spent co-writing, with his brother Lief Enger—a best-selling novelist in his own right—the Gun Pederson series of mystery novels for Pocket Books under the joint pseudonym L.L. Enger.

The novel’s setting and characterization symbiotically thicken the meaning of the story. Undiscovered Country is populated with a colorful set of characters: a once-aspiring actress turned desperate housewife; a failed rock star deeply envious of his brother’s rise to small-town success; an eccentric nitwit obsessed with the trumpet. Then, of course, there is Jesse himself, a gloomy brooder worthy of Shakespeare’s prince. The haunting North Woods of the Minnesota lake country, with its long and punishing winters, powerfully recalls cold, rainy, windswept Elsinore—a perfect setting to suggest a dystopia deeply out of joint. Enger ingeniously draws on the region’s deep Scandinavian roots to lace the atmosphere with cultural overtones of ancient Northern Europe. Jesse’s family restaurant Valhalla (“hall of the slain”) houses a giant Viking statue named Beowulf, as well as various Norse artifacts. These and other allusions emit an ominous and tragic miasma, reinforced by our own associations of old Germanic civilizations as mostly brutal and violent.

As a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Enger could be susceptible to the oft-repeated critical charge of the homogenization of American fiction. Yet Enger’s writing displays an incredible range and the confidence to exercise it, but only when the story calls for it, or, as Hamlet advises the players, “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.” A representative sample of Enger’s deceptively straightforward yet powerful prose occurs near the middle of the novel, where Jesse contemplates the nature of revenge, thematically one of the most compelling inquiries of both Hamlet and Undiscovered Country. Enger tunnels full force into the nature of retribution and justice.

Getting even, I think, is the most natural thing in the world, a physical law, like gravity. Somebody hits you, what do you do? Hates you? What do you do? There was this little toy that my dad had when I was small. I think it was called Newton’s cradle. He kept it on his desk in the basement. A line of five steel balls hung suspended, each by two strings, within a wooden frame. When you lifted a ball at one end and dropped it against its neighbor, the force of the strike transferred itself through the line of balls, causing the one at the other end to rise. When that one dropped, the original ball on the opposite end rose again. And so it went. If there were no such thing as friction, the back-and-forth motion would have gone on forever.

Most people, of course, don’t act on their thoughts of revenge. I realize that. But I’d argue that one way or another, they do manage to purge them. They snap at their wives or husbands, kick the dog, eat the last slice of pizza, curse the driver in front of them, disparage their co-workers.

These passages, written in a precise, stomach-punch vernacular, introduce a metaphor that strikes at the thematic heart of the novel and affords considerable insight into the protagonist’s conflicted character. Revenge is made more problematic in an age where rogue justice and the philosophy of an eye for an eye are considered unlawful and immoral by most of civilized society. A deep conflict arises between what Jesse sees as a biological imperative that switches on when one individual wrongs another—to get even, to restore balance to the moral universe—and the very necessary legal and ethical constraints that shore up modern civilization. The life-shaking events of the novel prompt Jesse to take solace in a clear-cut, mechanistic universe.

In Hamlet’s situation, avenging the murder of his father, the king, was natural, lawful, expected. If a wrong was not directly redressed, a prince risked being seen as weak and undeserving of kingship. Much of Hamlet’s self-loathing resides in what he perceives as his own cowardice, his inability to take action against Claudius. Jesse suffers in some ways from the opposite pressure: he lives in a society that does not sanction murderous revenge despite a widespread, innate urge to do so.

Part of this conflict is also rooted in Jesse’s adolescence, a period in which males are often attracted to extreme action in response to the complexities in coming of age. Indeed, Undiscovered Country can be read as a kind of bildungsroman, especially in its treatment of the protagonist’s movement from adolescence to adulthood through trials that explore the many tensions between the desires of the self and the broader demands of society.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Undiscovered Country is that it offers a rare kind of insight. A Shakespearean scholar once told me about a piece of memorabilia that he had come across in London. It was a small, square holographic token, similar to the kind found in cereal boxes. If tilted a certain way, Shakespeare appeared dressed as a soldier; if tilted another way, as a court jester, and so on. But if the token was held flat, and looked at straight on, the image vanished, revealing a small mirror. This token reminds us graphically that we can read Shakespeare in a wide variety of ways, but the most meaningful reading is the one that reveals to us our own selves. This is surely the mark of an enduring story; and if, as a first novel, Undiscovered Country is anything to go by, we can expect Lin Enger’s storytelling to reveal many more parts of our inexhaustible, perplexing, elusive nature in the future. ![]()