continued from v18n1’s “What Was Not His to Keep”

continued to v19n1’s “That Night Another Change”

Enough of Us Still and Brave Enough

| Kenneth Langer & Ellen Bryant Voigt Voices Program Notes Voices of 1918 William Bell Newton MacTavish

|

|

Donald Rae served with the 19th Battalion and was taken prisoner at Hangard Wood on 12 April 1918. Repatriated to Britain on 11 December 1918, he died a month later of pneumonia following on from influenza. Donald Rae is buried in Dumfries Cemetery, Scotland. His father chose his inscription: Through fire, wounds, prison / Came safely / Then gazing homeward / Died

—from Epitaphs of the Great War: The Somme by Sarah WearnI am intuitively convinced that there is a connection—psychic or otherwise—between this latest epidemic and the war that has been dominating the world for over four years; for both epidemics have their common source in fear.

—from A Scavenger in France by William Bell

Dear Mattie, did you have the garden turned?

This morning early while I took my watch

I heard a wood sparrow—the song’s the same

no matter what they call them over here—

remembered too when we were marching in,

the cottonwoods and sycamores and popples,

how fine they struck me coming from the ship

after so much empty flat gray sky,

on deck winds plowing up tremendous waves

and down below half the batallion ill.

Thirty-four we left behind in the sea

and more fell in the road, it’s what took Pug.

But there’s enough of us still and brave enough

to finish this quickly off and hurry home.

—from Kyrie by Ellen Bryant Voigt

We began our look at 1918 in v17n2 by featuring work from Ellen Bryant Voigt’s Kyrie, her 1995 book of untitled sonnets set during the influenza pandemic and World War I. We end our three-issue serial treament of the 1918–1919 pandemic with Voigt’s poems again included, this time as part of a Vermont Symphony Orchestra’s commission of composer Kenneth Langer for their “Made in Vermont” music series in the year 2000.

In the program notes for the composition Voices from 1918, Langer writes, “When I first read [Kyrie] I had never heard of the tragedy of 1918, and this came to me as quite a surprise. . . . It seemed to me to be a story worth telling and a story worth knowing. I thought it was also a story worth putting to music.”

Langer’s composition quotes portions of poems from Kyrie; each of the book’s sonnets is in the voice of a character, individuals speaking to the effect of the pandemic on themselves and their rural community. One voice, represented in the epigraph above, is that of a soldier, one of their own, writing back to them from the Great War.

|

|

Private Donald Mac Rae, an Australian soldier and victim of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. Dumfries Cemetery, Scotland. Find A Grave, database and images (www.findagrave.com : accessed 04 December 2019), memorial page for Pvt Donald Mac Rae (4 Jun 1896–15 Jan 1919), Find A Grave Memorial no. 71096519, citing Dumfries High Cemetery, Dumfries, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland ; Maintained by Find A Grave (contributor 8). |

|

The experience of soldiers during the pandemic are also represented in texts published in our first two installments; in this issue, we provide a nonfiction account of a noncombatant’s view of the war, and the so-called “Spanish Flu,” with selections from William Bell’s journals, published in 1920 as A Scavenger in France. Selected entries from May 1917–January 1918 introduce the writer as a Scottish architect who serves with the Friend’s War Victims’ Relief Committee (“Friends” being “The Religious Society of Friends,” or “Quakers.”)

Selected journal entries from July 27–December 24, 1918 are chosen chiefly for their mentions of the influenza pandemic, as well as Bell’s eclectic thoughts on the causes and nature of war and illness. Bell writes of his belief in the power of the human mind over illness and claims confidentally that he has “mentally inoculated” himself against influenza. Early in the journal entries he claims to feel no pain upon sawing off the tip of this thumb to the bone, and jokes about its subsequent regrowth (surprising to his coworkers) writing that “perhaps . . . it may be that this function of the lower animals which I have developed is convincing proof of the argument of our opponents who believe that the ‘conscientious objector’ belongs to the reptile species.”

|

|

A variation of the emblem representing the Friends’ War Victims’ Relief Committee. “Badges” worn on their uniforms were red and black. Fourth Report of the War Victims’ Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, October 1916 to September 1917 (London: Headley Brothers, 1917), title page detail. |

|

Bell writes descriptively throughout the book of the landscapes, art, and architecture with the eye of an architect and intellect, and he does not hesitate to speak to his disapproval of the war machine, nor to espouse his philosophies and beliefs. His Christian generosity extends to the enemy, particularly when he writes of German prisoners of war. His tone and generosity throughout the book stand, however, in all the starker and more shocking contrast to the overt racist language (not reproduced here) toward Black American soldiers that appears in one entry near the end of the book.

Rowland Kenney’s short story “Maisie,” set in an evocative London speakeasy called “The Cave”—a venue operated by the story’s title character—doesn’t overtly place itself within the 1918–1919 window of the pandemic, but it is published in The New Age in 1920. “Maisie” is one the few fictions we have found from the near historical moment that mentions influenza or uses it as a plot point. Memories of the pandemic would have remained sharply vivid at the time of publication.

|

|

The New Age: A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature, and Art. XXVI (April 22, 1920) cover detail. |

|

Newton MacTavish’s remembrance, “The Doctor,” published in 1921, is one of many essays published serially, under the series title Thrown In, in The Canadian Magazine of Politics, Science, Art, and Literature, a magazine where MacTavish also served as the editor. These essays are collected in a 1923 book, Thrown In. MacTavish is described in the introduction to the book as a humorist who embodies and expresses “the Canadian national spirit.” The opening commentator continues “Mr. MacTavish, on the side of creative form, has given the Humorous Essay in Canada a new meaning and power by raising it to a plane of authentic literary and spiritual dignity.”

The essays in Thrown In depict a rural Canadian community thirty years prior to publication, placing readers around or before 1890. “The Doctor,” though an account of that past, is a narrative in which influenza plays a significant role. And when MacTavish writes “Inflammation was as common then as influenza is now.” One can only imagine how such a reference might reverbeate for readers who were just a few years past the pandemic. MacTavish, in the passage just before that assertion, describes a character who “caught cold while sitting on the veranda” and “died within the week of inflammation of the lungs.” This too might have resonated strongly to those who survived a pandemic whose victims often died of pneumonia, even after surviving the flu.

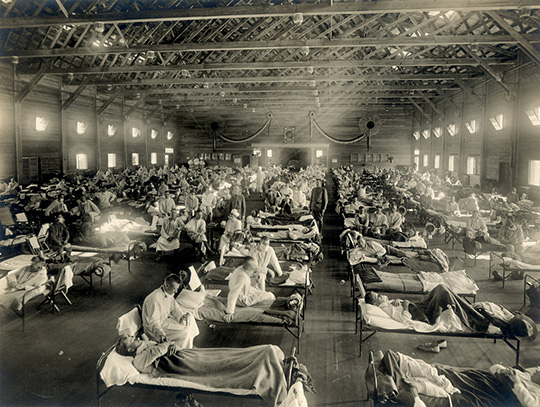

Finally, Pertinax (Andre Gerard) writes, in “The Codfish,” a brief, light, and loving portrait of a friend from whose nickname the essay title is taken, the friendship having begun in a an influenza ward in 1918. “Both of us were struck down; his bed was next to mine in the camp hospital; that is how we became friends. We talked commonplaces at first, common sense afterwards.” ![]()

|

|

Emergency Hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. The National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C., United States |

|